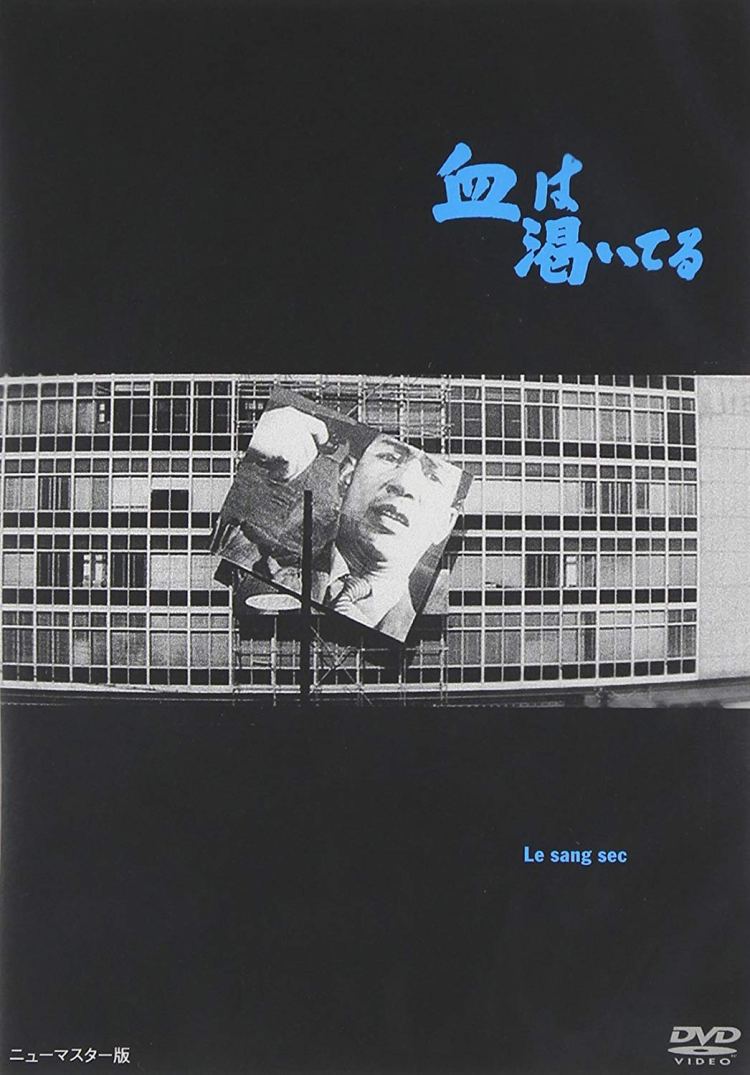

In the new post-war economy, everything is for sale including you! Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida’s second feature Blood is Dry (血は渇いてる, Chi wa Kawaiteru) takes its cues from Yasuzo Masumura’s earlier Technicolor corporate satire Giants and Toys, and Frank Capra’s 1941 comedy Meet John Doe in taking a faceless corporate drone and giving him a sense of self only through its own negation. The little guy is at the mercy not only of irresponsible capitalist fat cats, but of his own imagination and the machinations of mass media who are only too keen to sell him impossible dreams of individual happiness.

In the new post-war economy, everything is for sale including you! Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida’s second feature Blood is Dry (血は渇いてる, Chi wa Kawaiteru) takes its cues from Yasuzo Masumura’s earlier Technicolor corporate satire Giants and Toys, and Frank Capra’s 1941 comedy Meet John Doe in taking a faceless corporate drone and giving him a sense of self only through its own negation. The little guy is at the mercy not only of irresponsible capitalist fat cats, but of his own imagination and the machinations of mass media who are only too keen to sell him impossible dreams of individual happiness.

The action opens with a grandstanding rooftop speech from a former CEO to his distressed workforce informing them that because of “indifferent capitalism” this small business is going bust and everyone’s out of a job. Then, dramatically, our hero Kiguchi (Keiji Sada), steps out with a pistol and threatens to shoot himself, proclaiming that he no longer cares for his own life but doesn’t want anyone else to lose their job. Another worker, Kanai (Masao Oda), tackles Kiguchi and the gun goes off. Thankfully, he is only mildly wounded but Kiguchi’s case reaches the papers who make it into a human interest issue exemplifying the precarious economic conditions of the modern society. While he’s still somewhat current, an enterprising advertising executive hits on the idea of getting Kiguchi to act as the face of their campaign, bizarrely attempting to sell life insurance with the image of a man putting a gun to his head while proclaiming that “it’s high time everyone is happy”.

When we first meet him, Kiguchi is indeed a faceless, broken man at the end of his tether. His noble sacrifice is interpreted as an act of war on an unfair capitalist society, but as he later affirms in exasperation, Kiguchi had no political intent and never considered himself as acting with a greater purpose, he was simply terrified at the prospect of losing his job which is, in a sense, also his entire identity. Shy and mild-mannered, he stammers through speeches and curls himself into a hostile ball of awkwardness in front of the camera but ad exec Nonaka (Mari Yoshimura) is sure that only makes him a better sell for being “real” and relatable. Like the hero of Meet John Doe, however, Kiguchi starts to buy into his own hype. He fully embraces his role as the embodiment of the everyman, at once gaining and losing an identity as he basks in the unexpected faith of his adoring populace.

Kiguchi’s conversion wasn’t something Nonaka had in mind and it frightens her to realise she has lost control of her creation. Meanwhile, Nonaka’s ex, a paparazzo with a penchant for setting up celebrities in compromising situations in order to blackmail them, has it in for Kiguchi as the personification of his own dark profession. He resents the idea of using “suicide” as a marketing tool and the cynical attempt to sell the idea of happiness through the security of life insurance which, it has to be said, is a peculiarly ironic development.

Kiguchi’s liberal message of happiness and solidarity does not go down well with all – he’s eventually attacked in a taxicab by a right-wing nationalist posing as a reporter who accuses him of being a traitor to Japan, and it’s certainly not one which appeals to the forces which created him. Nevertheless, he does begin to capture something of the spirit of the man in the street who just wants to be “happy” only to have his message crushed when his image is tarnished by tabloid shenanigans and left wondering if the only way to reclaim his “artificial” identity is to once again destroy himself in sacrifice to his new ideal.

Yet Kiguchi’s motivation is both collectivist and individual as he claims and abandons his identity in insisting that he belongs to the people. His confidence is born only of their belief in him and without it he ceases to exist. Kiguchi’s entire identity has been an artificial creation with an uncertain expiry date and his attempts to buy it authenticity only damn him further while his actions are once again co-opted by outside forces for their own aims. The little guy has achieved his apotheosis into a corporate commodity leaving the everyman firmly at the mercy of his capitalist overlords, dreaming their dreams of consumerist paradise while shedding their own sense of self in service of an illusionary conception of “happiness”.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate.

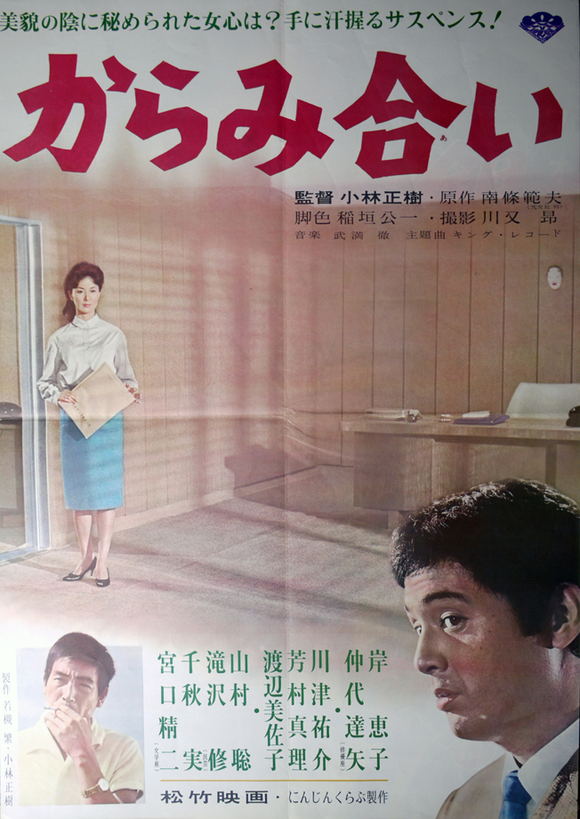

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate. Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth.

Kobayashi’s first film after completing his magnum opus, The Human Condition trilogy, The Inheritance (からみ合い, Karami-ai) returns him to contemporary Japan where, once again, he finds only greed and betrayal. With all the trappings of a noir thriller mixed with a middle class melodrama of unhappy marriages and wasted lives, The Inheritance is yet another exposé of the futility of lusting after material wealth.