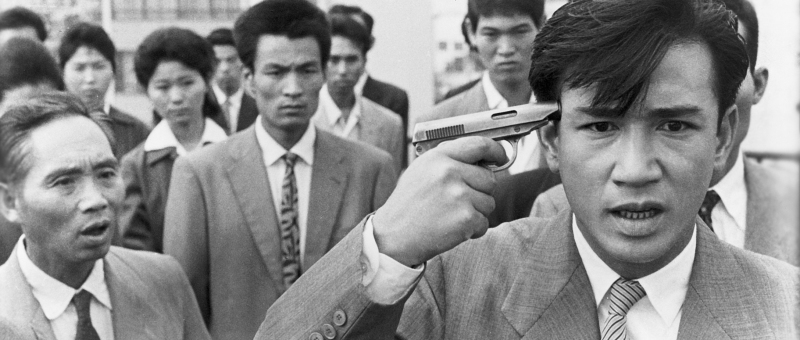

Like many directors of his generation, Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida began his career at Shochiku working on the studio’s characteristically inoffensive fare before being promoted as one of their youth voices through which they hoped to capture a similar audience to that attracted by Nikkatsu’s Sun Tribe movies. Yoshida’s films may have spoken to youth but they were perhaps not quite what the studio was looking for nor the kinds of projects that he really wanted to work on, which is one reason why 1964’s Escape from Japan (日本脱出, Nihon Dasshutsu), an anarchic B-movie crime thriller of intense paranoia all maddening angles and claustrophobic composition, was his last for Shochiku, the final straw being their decision to change the ending without telling him and release the film while he was away on honeymoon.

Set very much in the present, the film opens with a young man miming to American jazz which turns out to be part of the floor show being performed by the band on the stage below for whom he is a reluctant roadie. Tatsuo (Yasushi Suzuki) dreams of going to America to rediscover “real jazz” and subsequently bring it back to Japan. He has the strange idea that America is a true meritocracy where his talent will be recognised, unlike Japan where it is impossible for him to succeed because he is not particularly good looking or possessed of “star quality”. Feeling himself indebted to the band’s drug-addled drummer Takashi (Kyosuke Machida) for helping him get the roadie gig with the false promise of becoming a singer, Tatsuo agrees to help him commit an elaborate robbery of the “turkish bath” (low level sex services and precursor to the modern “soaplands”) where his girlfriend Yasue (Miyuki Kuwano) works. Only it all goes wrong. The guys kill a policeman during the escape, and the other hotheaded member of the gang becomes convinced that Yasue may talk now that they’ve got involved with murder so they should finish her off too by forcing her to take an overdose of sleeping pills.

Absolutely everyone is desperate to escape Japan for various different reasons. Tatsuo because of his obsession with American jazz and the freedom it represents to him coupled with the sense of impotence he feels in an oppressive society which refuses to recognise his talent because he doesn’t look the part. He jokes with his next-door neighbour, a sex worker who has redecorated her apartment in anticipation of impressing the tourists arriving for the Olympics, that he envies women and wishes he could find a “sponsor” to take him to the States, but later can offer only the explanation that Japan doesn’t interest him when probed over why he was so desperate to leave.

“Korea or anywhere else, it’s better than Japan” Yasue later adds, consoling Tatsuo as she informs him that their escape plan won’t work because all of the US military planes are being diverted to Korea to bring in extra help for the Olympics. Bundled into a van filled with chicken carcases as a potential stowaway, he discovers another escapee – a Korean trying to go “home”, or rather to the North (presumably having missed out on the post-war “repatriation” programs) where he claims there are lots of opportunities for young people only to lose his temper when Tatsuo explains that he wants to become a jazz singer. He doesn’t want decadent wastrels in his communist paradise and would rather Tatsuo not mess up his country. Yet they are each already dependent on the Americans even for their escape, making use of military corruption networks and getting Yasue’s friend’s GI squeeze into trouble through exposing his black-marketeering.

Tatsuo and Yasue find they have more in common than they first thought, both “deceived” by those like Takashi who turned out to be a feckless married man and father-to-be risking not only his own future but that of his unborn child solely to fuel his escapist drug habit (which was perhaps the reason for the lengthy hospital stay from which he had just returned). Yasue was just trying to save up enough money to open a hairdresser’s in her hometown, but Takashi told her he was a “famous jazz drummer” and presumably sold her the same kind of empty dreams as he did Tatsuo. Giving up on her own future, realising that even in America the sex trade is all that’s waiting for her, Yasue tries to engineer Tatsuo’s escape but he, traumatised by his crimes, descends further into crazed paranoia, eventually finding himself right in the middle of the Olympics opening ceremony. This is event is supposed to put Japan back on the map as a rehabilitated modern nation, but perhaps all it’s doing is creating an elaborate smokescreen to disguise all the reasons a man like Tatsuo and a woman like Yasue might want to be just about anywhere else. Yoshida seems unimpressed with the modern nation and its awkward relationship with the Americans, perhaps a controversial point in the immediate run up to the games. Shochiku neutered his attempt to depict a man driven to madness by the impossibilities of his times, but a sense of that madness remains as Tatsuo finds himself on the run and eventually suspended neither here nor there, trapped in a perpetual limbo of frustration and futility.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

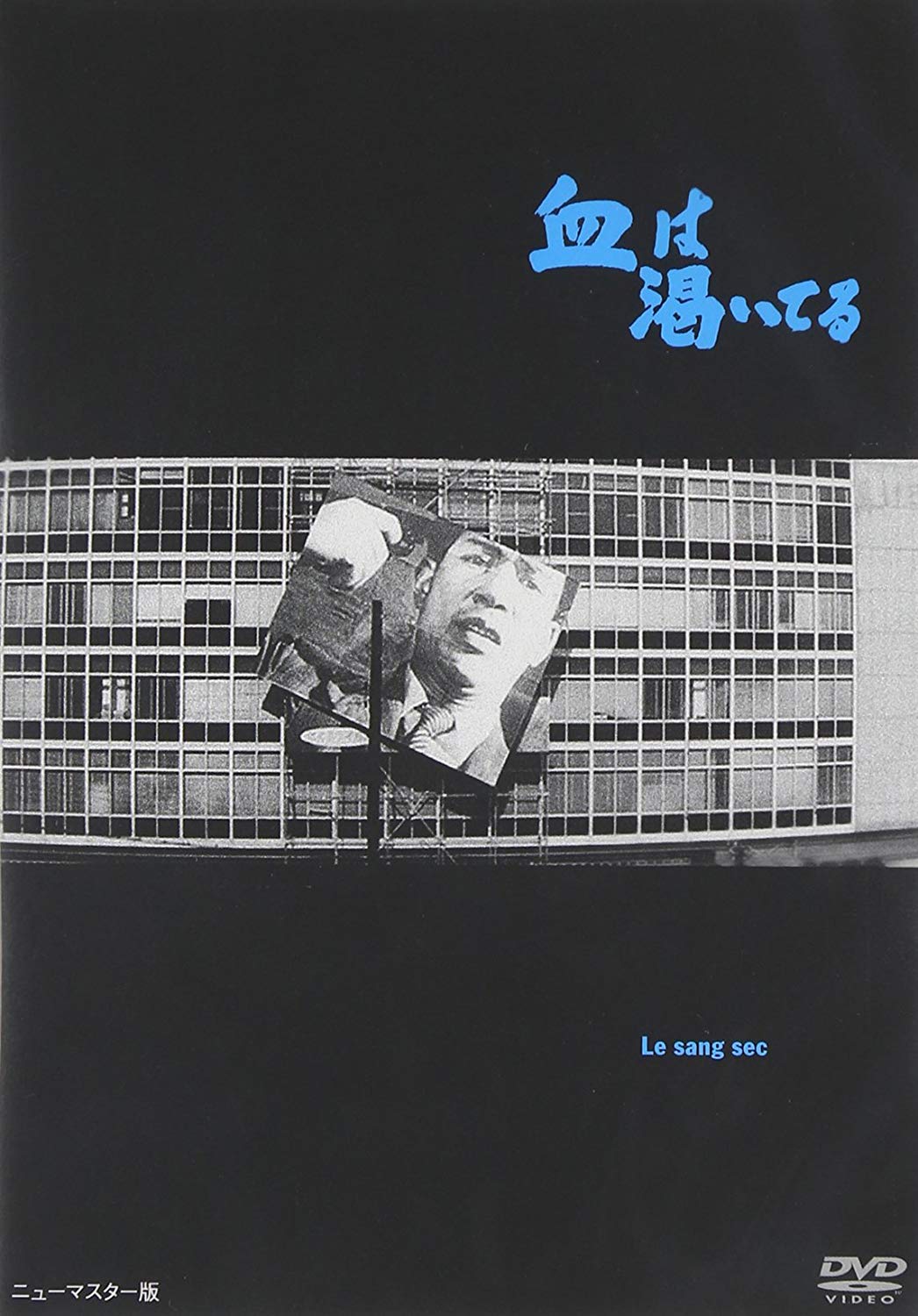

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate.

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate. Of all the post-war Japanese filmmakers, the one who liked to twist the knife the most was surely Oshima. No subject too taboo, no pain too raw – he liked to find the sore spot and poke at it a little, if only in the hope of encouraging an accelerated healing, albeit one which would leave a scar to remind you that once you suffered. With Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (戦場のメリークリスマス, Senjou no Merry Christmas) he takes an unflinching look at the treatment of Japan’s prisoners of war and contrasts the Japanese forces with the different attitudes of the (mostly) British soldiers held within the walls of the camp.

Of all the post-war Japanese filmmakers, the one who liked to twist the knife the most was surely Oshima. No subject too taboo, no pain too raw – he liked to find the sore spot and poke at it a little, if only in the hope of encouraging an accelerated healing, albeit one which would leave a scar to remind you that once you suffered. With Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (戦場のメリークリスマス, Senjou no Merry Christmas) he takes an unflinching look at the treatment of Japan’s prisoners of war and contrasts the Japanese forces with the different attitudes of the (mostly) British soldiers held within the walls of the camp.