An aspiring street dancer from an impoverished background just can’t seem to catch a break no matter how hard he works in Dong Chengpeng’s inspiring dramedy One and Only (热烈, rèliè). A mild rebuke against a rising fuerdai generation of obnoxious narcissists who don’t think twice about using their money to game the system, the film not only emphasises the virtues of hard work and perseverance but the importance of camaraderie and fellow feeling over an individualistic drive to succeed.

The conflict is encapsulated in the opening sequence in which hotshot dancer Kevin starts a fight with one of his own team members in the middle of dance competition over a move that didn’t go as planned. The problem is that Kevin is an obnoxious rich kid whose US-based father has been bankrolling the team. He plans to sack most of the other dancers and replace them with foreign ringers, only manager Ding (Huang Bo), who dared to suggest the problem was he doesn’t practice enough with his teammates, isn’t so sure. In an effort to appease him, he hires a ringer of his own in Shou (Wang Yibo), an aspiring dancer who auditioned for the team but didn’t get through, booking him to stand in for Kevin during rehearsals with the caveat that he won’t actually get to perform in any of their concerts or competitions.

Kevin is not untalented, but his path has been easy wheareas Shou is doing a series of part-time jobs in addition to helping out in his mother’s restaurant while burdened by debts as a result of his late father’s illness. Yet he never gave up on his street dancing dream, working with his uncle doing a series of humiliating gigs at shopping malls and birthday parties never complaining but grateful for the opportunity to dance. The offer from Ding is the answer to all his prayers, but also a cruel joke in that he’s only there to sub in for rich kid Kevin until such time as he feels like showing up again.

Ding is aware of the choice he faces even as he forms a paternal relationship with Shou whose father was also a breakdancer. To redeem himself and achieve his dreams of national championship glory, Ding thinks he has to choose Kevin and his unlimited resources but is also drawn to Shou’s raw passion and pure-hearted love of dance if also mindful of the “realities” of contemporary China where money and connections are everything and boys like Shou don’t really stand a chance because socialist work ethics are now hopelessly outdated. Ding may be outdated too, even his old friends who got temporarily rich during an entrepreneurial boom have seen their dreams implode in middle age and are currently supplementing their incomes as substitute drivers for partying youngsters.

Tellingly, after Kevin has them kicked out of the gym he paid for, the team start training in an abandoned factory theatre from the pre-reform days where Shou’s parents used to perform, quite literally resetting their value systems after jettisoning Kevin to focus on team work and unity. Then again in a mild paradox, Ding realises that he shouldn’t lead the team by dominating It but support from within which results in a kind of democracy as he holds a secret ballot to decide whether they should stick with Kevin and a certain, easy victory, or reinstate Shou and take their chances the old-fashioned way.

Of course, the team choose hard work and perseverance, never giving up even when it seems impossible, leaving the obnoxious Kevin to his self-centred narcissism. Kevin only really wanted backing dancers which is why he couldn’t gel with the team, whereas when challenged one on one Shou does each of his teammates signature moves proving that he’s mastered a series of diverse dance styles along with his own high impact headspring move. Heartfelt and earnest, the film shines a light on a number of issues from middle-aged disappointment and the moral compromises involved in chasing a dream but in the end reinforces the message that there are no shortcuts to success which can never be bought with money but only through sweat and tears along with teamwork and the determination to master one’s craft.

Original trailer (Simplified Chinese / English subtitles)

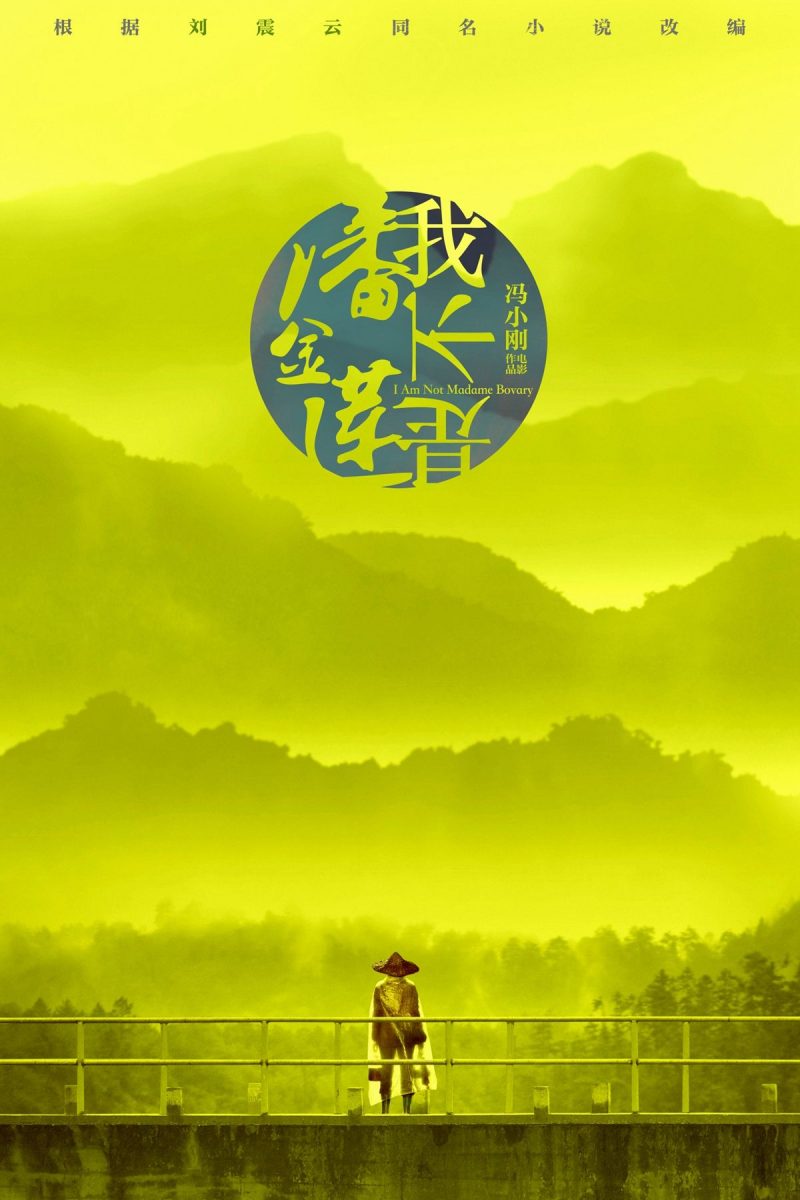

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and

Feng Xiaogang, often likened to the “Chinese Spielberg”, has spent much of his career creating giant box office hits and crowd pleasing pop culture phenomenons from World Without Thieves to Cell Phone and You Are the One. Looking at his later career which includes such “patriotic” fare as Aftershock, Assembly, and