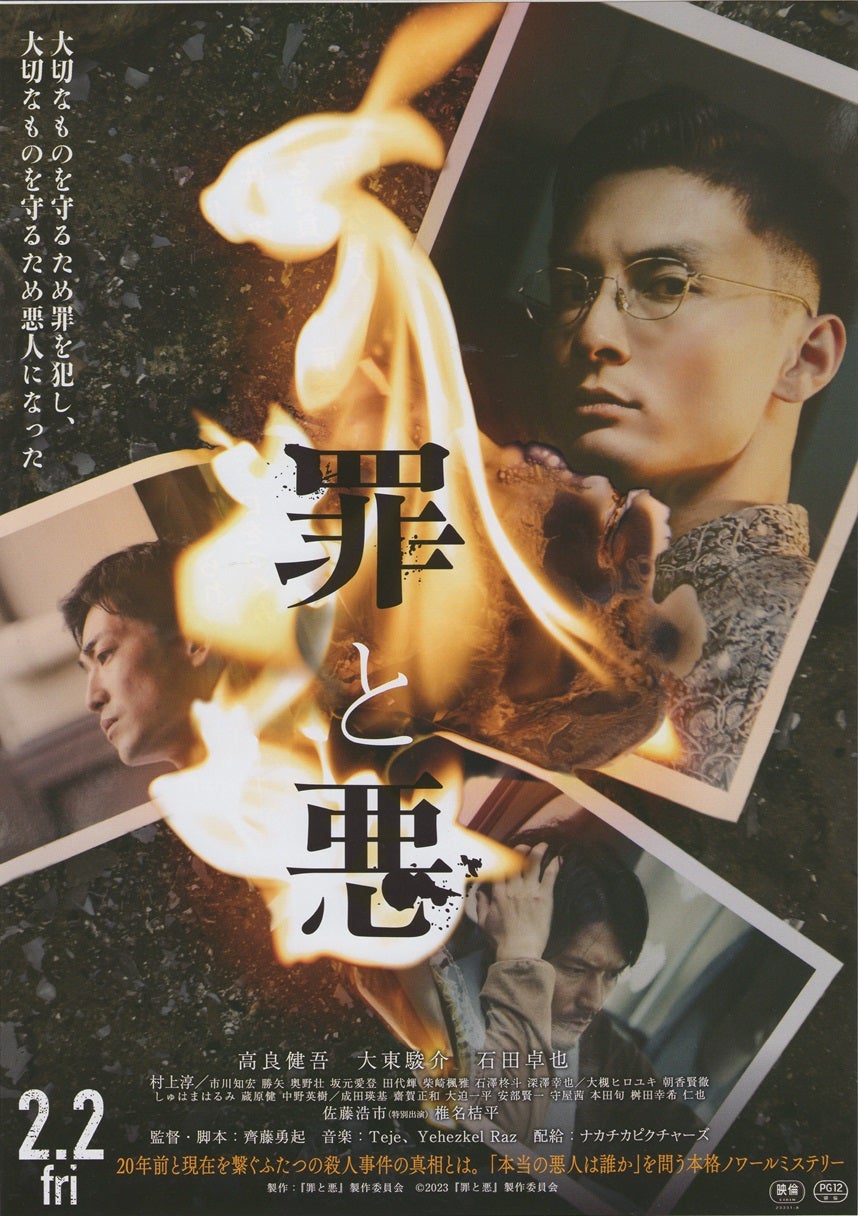

A man not quite a yakuza and perhaps even what might be termed an ethical gangster tells one of his underlings that it isn’t a sin unless you believe it it is, which might in a sense be true in same way as Socrates says that no one does wrong willingly. Yet the heroes of Sin and Evil (罪と悪, Tsumi to Aku), Yuki Saito’s small-town crime drama, are marked by their guilt while trying to come to terms with traumatic events of 20 years earlier and their mutual decision to cover them up.

Echoing similarly themed films such as Stand By Me, Saito opens with idyllic scenes of the boys riding their bikes with the only hint of darkness offered by a disturbing conversation about an elderly man who is rumoured to be abusing children. However, it seems that Haru is living in a difficult domestic situation following the death of his sister with an abusive father and apparently neglectful mother. His best friend, Akira, is the son of a local policeman while the boys are also friends with a pair of twins, Saku and Naoya, whose family operate a tomato farm. Rounding up the group is Masaki who also seems to be living in difficult circumstances though his backstory is never fully fleshed out as he’s eventually found dead in a local river. Saku jumps to the conclusion that the old man must have abused Masaki, who was known to be friendly with him, and then killed him to keep him quiet. He drags Haru and Akira to the old man’s shack where he attacks and eventually kills him with a shovel. Haru decides to take the blame and torches the place, telling the other two boys to flee the scene.

20 years later, it’s clear that each of them are still marked by what happened that day though Haru (Kengo Kora) appears to have built a good life for himself after serving time in juvenile detention even if the construction company he runs is friendly with local yakuza and gets its contracts through small-town corruption. He also operates a cafe where he employs delinquent boys while secretly using them as thieves but also in a more genuine sense looking after them and concerned for their welfare. His machinations are seen to be key in keeping order, working in tandem with police Inspector Sato (Kippei Shiina) who explains to a more idealistic Akira (Shunsuke Daito) how things are done around here which is essentially keeping ordinary people safe by managing crime rather than punishing or preventing it. The balance is only disrupted by some of Haru’s boys who stupidly steal far too much money from the local yakuza. Haru attempts to protect the young man concerned, but his body soon ends up in the river in exactly the same place as Masaki raising a series of questions about the nature of the earlier crime.

What the film is trying to do is paint the world in shades of grey while looking for the parts where it’s darkest. It seems it’s not in doubt that the old man abused local children, though Haru and Akira now doubt he killed Masaki raising further questions about their killing of him. As the yakuza underling had said, it’s not a sin unless you think it is and Haru feels that he deserved to die for what he did to other kids so doesn’t feel any remorse for his actions even if he didn’t kill Masaki. But for Akira, the trauma lingers in other ways and he’s disturbed on learning his father may have been involved in covering up their crime and at least complicit in police corruption essentially teaching Sato how things are done in small-town policing. The conclusion Haru comes to is that they are all victims of the town itself, unable to break free of its provincial mores and petty prejudices.

Those would largely be a lingering homophobia and deep shame stemming from suffering sexual abuse as a child. As usual with these kinds of mysteries, the solution lies in the desire to prevent the truth being exposed though in this case the resolution is not entirely convincing when using one killing to cover up another couldn’t help but expose the truth anyway even when attempting to pin it on someone else who can no longer defend themselves. It also sidesteps the themes of small-town corruption and the dark heart of suburbia even as Haru points out that someone should have stepped in to support both himself and Masaki when they could see their families were struggling rather than just closing their curtains and pretending not to notice. The disruption of the friendship, which ought to be the heart of the drama, therefore lacks poignancy muddied by the various overlapping plot lines from the present day yakuza drama to the lost paradise that Haru longs to reclaim despite the otherwise apparently happy life he seems to be living now. Sin, the film seems to say, is in the eye of the beholder along with justice and retribution, and evil maybe just the same or merely invisible to those who choose not to see it.

Sin and Evil screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

International trailer (English subtitles)

There are two very distinct sides to the career of Tatsushi Omori. Brother of the well known actor, Nao, Omori may be best known to certain audiences for his hard hitting, often gloomy and pessimistic dramas of human misery such as festival favourite Ravine of Goodbye or the little seen

There are two very distinct sides to the career of Tatsushi Omori. Brother of the well known actor, Nao, Omori may be best known to certain audiences for his hard hitting, often gloomy and pessimistic dramas of human misery such as festival favourite Ravine of Goodbye or the little seen