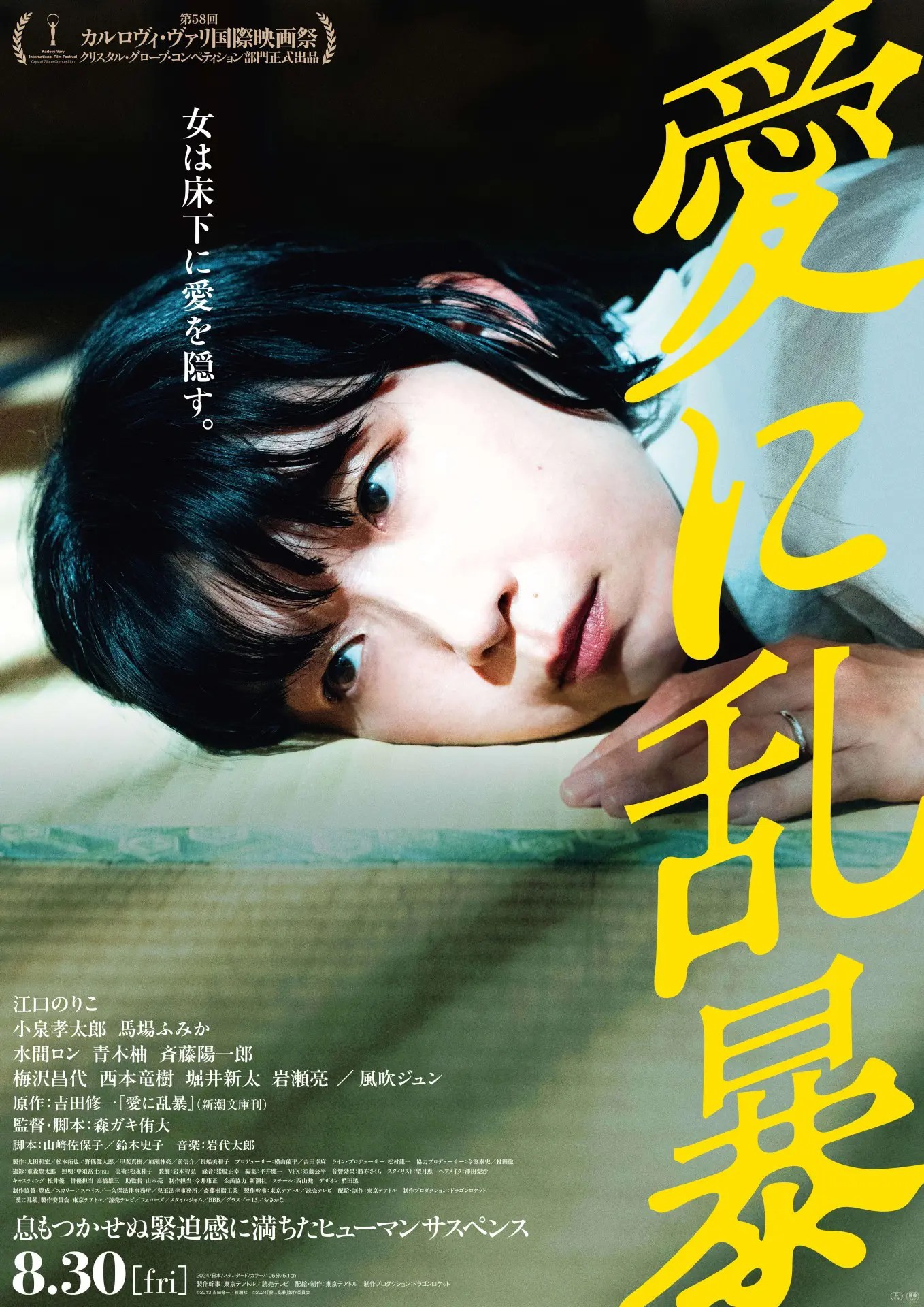

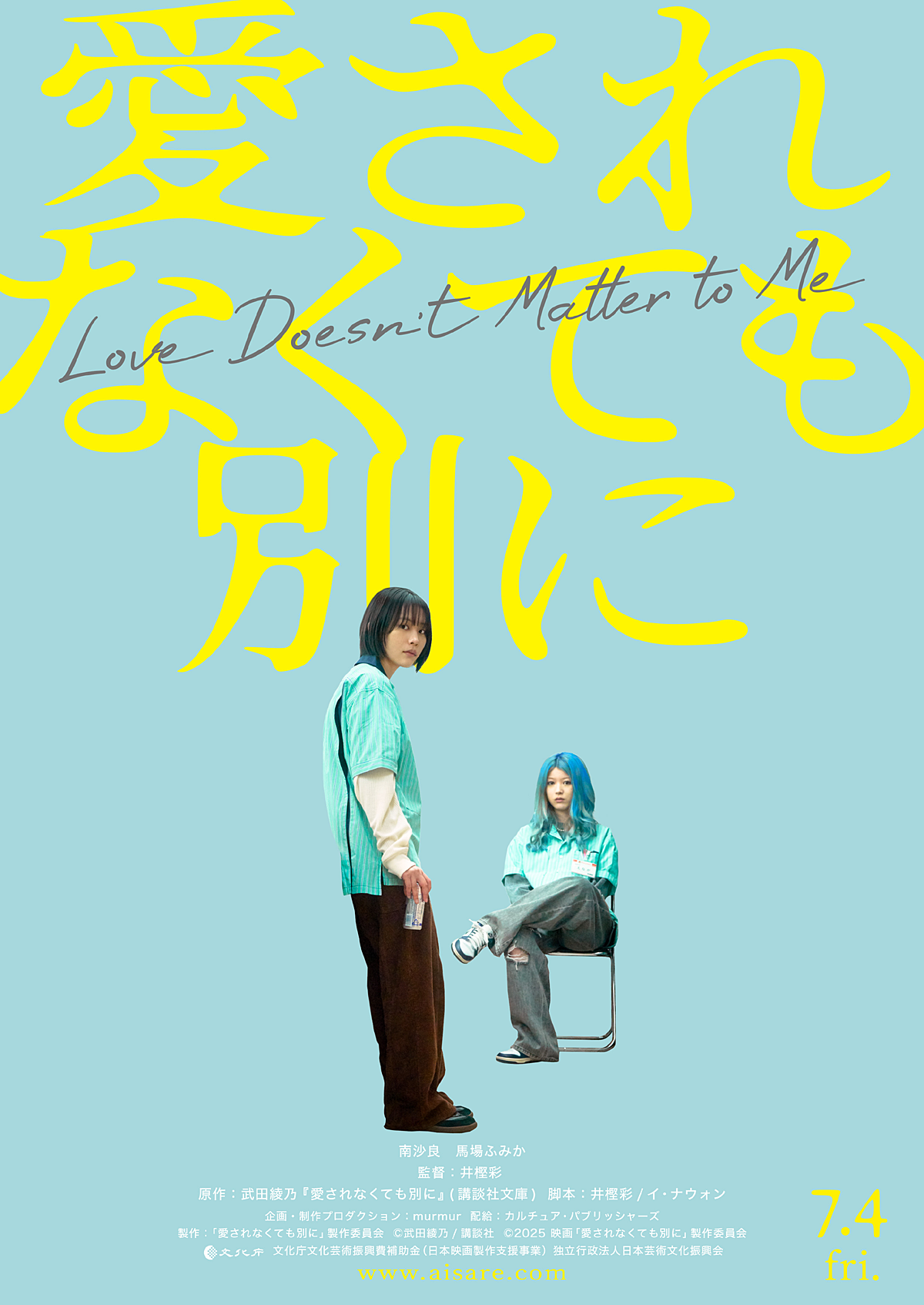

Two young women find solace and solidarity in each other after escaping toxic familial environments in Aya Igashi’s adaptation of the novel by Ayano Takeda, Love Doesn’t Matter to Me (愛されなくても別に, Aisarenakutemo Betsuni). Though some might say that parents always love their children even if that love was not conveyed in the optimal way, the two women struggle with their contradictory impulses in craving the love of a parent who in other ways they know is past forgiveness.

The problem for Hiiro (Sara Minami) is that the roles have become reversed. She is effectively the parent of her irresponsible mother (Aoba Kawai) who treats her like a housekeeper and is intent on exploiting her labour. Hiiro’s mother didn’t want her to go to university and is still charging her rent and board to live at home while Hiiro works several part-time jobs to jobs to support them. She believes that her mother lives beyond her means, but is unaware of the extent to which she’s been financially abusing her by keeping both the child support her absent father had been sending and the student loan she’d taken out as a safety net. Having to work so hard also means that Hiiro is tired all the time and is prevented from taking part in normal university life or social activities which leaves her unable to make friends. At times she resents her mother so much she’s worried she might end up snapping and killing her to be free, but at the same time loves her and therefore puts up with her ill-treatment.

Enaga (Fumika Baba), meanwhile, is ostracised because her father is on the run after killing someone, though the reason she is resentful of her family is a history of sexual abuse and exploitation that have left her feeling worthless. As she later says there’s no point comparing your unhappiness to that of other people, otherwise you just end up making yourself more miserable as if you were trying to win an unhappiness competition. Nevertheless, learning of Enaga’s situation wakes Hiiro up to the possibility that other people are unhappy too and her life may not have been as comparatively bad as she felt it to be in the depths of her isolation.

Yet what both women seem to crave is the positive maternal relationship they’ve each been denied. Hiiro gets to know another student, Kimura (Miyu Honda), who also has no friends partly owing to a judgemental attitude and poor social skills whom she later discovers to be from a wealthy background despite her being desperate to find a job and working alongside Hiiro at the convenience store. Kimura resents her mother (Shoko Ikezu) for being overly controlling and possessive. She’s come all this way to university to escape her, yet her mother calls every few hours and is angry if she doesn’t answer and makes frequent visits leaving Kimura with no freedom or social output. To Hiiro, Mrs Kimura’s actions seem to come from an obviously loving place and she might have a point that Kimura is naive, having been kept sheltered all life by her own helicopter parenting, which is why she’s been sucked into a cult. Hiiro sees in Mrs Kimura the love and affection she’d have liked from her own mother and is jealous rather than seeing how seeing Kimura feels suffocated and is driven to despair in being unable to escape her mother’s control.

Lady Cosmos (Yoko Kondo), the cult leader in whom Kimura has found salvation, tells each of the girls that they were loved by their imperfect parents and ought to love them back, but they seem to know better. Though she makes some perspicacious comments, Lady Cosmos also tells them exactly what they want to hear and attempts to occupy a more positive material space to be the loving mother they never had. But, of course, not so different from Hiiro’s mother, she’s bleeding Kimura dry by forcing her to pay extortionate amounts for readings and holy water. Ironically she’s still controlling her much like her own mother had, but Kimura thinks she’s found freedom in cult and resents any attempt to undercut Lady Cosmos’ belief system even if she’s at least on one level forcing herself to believe it rather than being a true believer.

What might be surprising is that the two women effectively break free of the “cult” of family in accepting that their parents aren’t good for them and the decision to cut them out of their lives is valid rather than the breaking of a taboo or an unnatural rejection of the sacred bond between a mother and a child. Instead they effectively remake the image of family for themselves as one of mutual solidarity and unconditional love between two people who aren’t related by blood but have discovered a much deeper bond rooted in shared suffering.

Love Doesn’t Matter to Me screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (English subtitles)