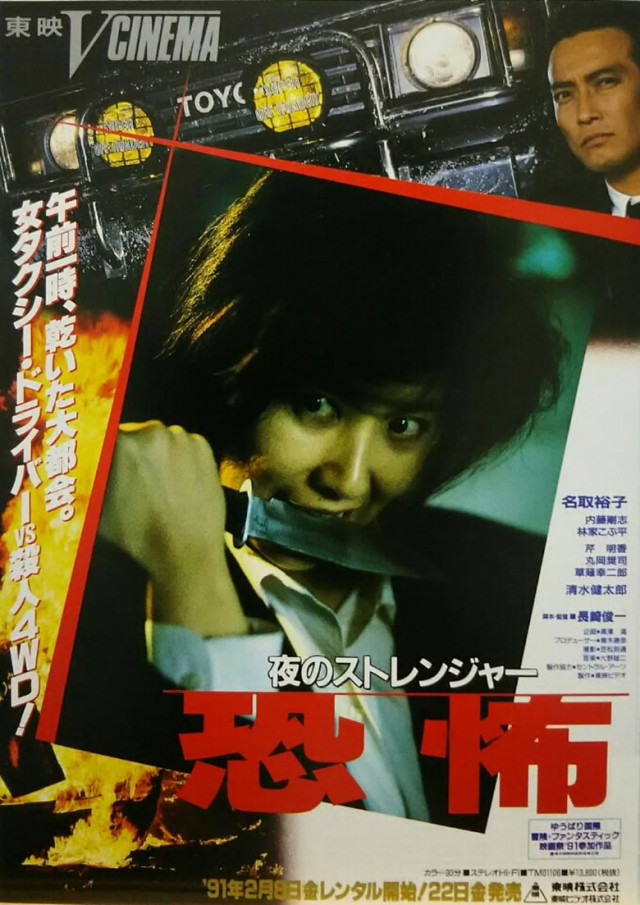

Driving through the city by night, a young woman finds herself plagued by a mysterious force while struggling to break out of her self-imposed inertia in Shunichi Nagasaki’s moody thriller, Stranger (夜のストレンジャー 恐怖). The film’s Japanese title, “night stranger terror”, perhaps more clearly hints at a sense of urban threat while surrounded by so many unfamiliar people, yet it is in many ways Kiriko’s (Yuko Natori) mistrust and suspicion that isolates her from the surrounding society and keeps her trapped in a kind of limbo unable to escape her past.

It might be tempting to read her aloofness as a direct consequence of her experiences, but in an early scene when she was still a bank employee we hear a colleague criticise her for being “anti-social” while Kiriko’s rejection of her seems born more of contempt than shyness or a preference for solitude. Working as a cashier at the bank at the tail end of the bubble is a pretty good job, especially given the still prevailing sexism of the working environment, that positions Kiriko firmly within an aspirant middle-class. She still lives at home surrounded by her family, but is in a relationship with a man who pressures her for money to invest in the stock market. She begins embezzling and lives as if there’s no tomorrow, splashing out on fancy sunglasses before meeting her boyfriend having left work early feigning illness. Unfortunately for her, she gets caught and her boyfriend predictably abandons her.

Just like the asset bubble, her life implodes and plunges her into a lower social stratum as a woman with a criminal conviction for financial impropriety and a hefty debt in needing to pay back the money she stole from the bank for her ex’s harebrained stock speculation schemes. All in all, you could say she’s been betrayed by economic forces, but also as she later admits, but her own uncertain desires in being wilfully deceived by Akiyama (Takashi Naito) and making a clear choice to defraud the bank. She realises that it might not have been a desire to please Akiyama that led her to do it, but the illicit thrill she felt in tapping away on her keyboard stealing the money and otherwise being in a position of economic power over a man, buying him things and taking him out for fancy food. Her sense of malaise is only deepened when she meets Akiyama by chance and tries to tell him all this, but he isn’t really interested. He seems to have moved on and planning to marry another woman.

Kiriko tries to look at his hands to see if he has burn scars like the man who attacked her in her taxi, but he doesn’t. Perhaps there was a small part of her that wanted it to be him. At least if it was, it would mean he still felt something for her, which would also prove that he ever did. And it would make sense, which is less frightening than her stalker just being a nutty fare, another irate man with a nondescript grudge wandering the city. Taxi driver is one of the few jobs open to her with a criminal record, but it’s also an unusual profession for a woman which further isolates her in her working environment. Her boss keeps calling her “little lady,” while patronisingly offering to put her on the day shift because it’s less dangerous. Kijima (Kentaro Shimizu), an obnoxious colleague, picks at Kiriko for thinking everyone who strikes up a conversation must be sexually interested in her. But the truth is that they are and like Kijima demand her attention. When they don’t get it they’re pissed off. The cab is perhaps the place she feels the most safe, though she faces her fair share of weird fares from drunk men trying to flirt to religious maniacs proselytising from the back seat.

Now living alone in an apartment, her aloofness is both a personal preference and means of punishing herself. When her brother calls, he encourages her to come home but she says she can’t even though she wants to because she hasn’t yet dealt with her past or taken steps towards being able to forgive herself. She tells Kijima, who in truth behaves in an incredibly creepy way that suggests she’s right to avoid him, that she wonders if she isn’t the only one who can see the mysterious Land Cruiser, as if she were really imagining it. The Land Cruiser does indeed come to stand in for the buried past by which Kiriko is haunted and her eventual besting of it is a symbolic act that suggests she’s finally managed to overcome her guilt and shame to be able to leave the past behind.

As she told Kijima, this was something only she could do by her own hand or none. Akiyama’s dismissiveness of her reflects the fact that he couldn’t give her this absolution either, she needed to find it for herself. Kijima accused her of still being hung up on the guy that scammed her, but that wasn’t quite it. The resolution might hint at his being right when he told her that she needed to learn to trust people more in that it seems to lead to a greater willingness to open herself up to the world. Once again, her sunglasses get broken as a new truth becomes visible to her. A lonely little boy she meets who, like her, enjoys driving in circles and going nowhere, probes her lack of human connection by suggesting that she doesn’t know what it’s like to love someone which is why she can’t understand his obviously inappropriate love for her, though it’s a fact that Kiriko has to acknowledge is truth in interrogating the reality of her relationship with Akiyama.

Nevertheless, in the end, she saves herself and embraces her solitude and independence looking out at the peaceful bay in a city that no longer seems so threatening even if the unseen threat in this case did turn out to be random and have no rational explanation. Nagasaki never again worked in the realms of V-Cinema and his entry is fairly atypical in starring an older, established actress as an action lead while requiring no nudity or sexual content, instead quite literally allowing her to grab the wheel and take control of her life to claim freedom and independence rather than solely romantic fulfilment.