In many ways, the underlying theme in Akira Kurosawa’s films of the 1950s is that we are incapable of knowing ourselves and are, as a forest spirit remarks in Throne of Blood (蜘蛛巣城, Kumonosu-jo), afraid to look into our own hearts and admit our darkest desires. In adapting Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Kurosawa is less interested in the pull of ambition than the insecurity that drives it along with the inability to transcend himself that precipitates the hero’s decline.

Indeed, after Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) and his best friend Miki (Minoru Chiaki) ride into the misty forest domain of the witch-like seer who ominously turns her spinning while offering a moral lesson that neither of them heed, they sit on the ground and laugh about what they’ve heard. Yet as Washizu partly admits the old woman revealed something of himself to him in that she echoed a dream of which he was unwilling to speak. Miki asks what warrior would not want to be placed in charge of a castle, but for Washizu it’s almost a primal need to prove himself in surpassing other men. Miki, by contrast, is not so nakedly ambitious but he doesn’t really need to be because he has a son. Washizu has no heir, his line will end with him and so he has only this life to make something of his name.

Having no heir also undermines his sense of masculinity, just as it undermines the femininity of his wife, Lady Asaji (Isuzu Yamada), who as a woman now likely too old to bear a child may fear for her position. Kurosawa styles Yamada’s face as a perfect noh mask while she delivers her lines with the intonation of noh theatre all of which lends her a fairly eerie presence which only deepens as she descends into the darkness and back out again hovering like a ghost. She is in a sense perhaps already dead if not otherwise possessed by some malignant spirit as she urges her husband on in their dark deeds like a demon on his shoulder even going so far as to present him with the spear he will use to murder his lord, the ultimate act of samurai transgression.

Yet as Lady Asaji points out, the present lord killed the lord before him for the right to sit on the dais. When the lord comes to stay with them on a pretext of hunting while preparing to launch an attack on a potential rival, the couple are moved into a room previously inhabited by a retainer who’d tried to mount a rebellion but was defeated. He took his own life and the room is still stained with his blood which covers both walls and floor. Washizu ought to realise that this is his fate too, but deep down he wants the prophecy to be true, which it is if more in the letter than the spirit. Would he have done it if he had not met the forest spirit, or would he only idly have thought of it but never followed through? It’s not something that can be known, but his eventual failure is born more of his inability to accept this side of himself than it is the price of ambition in itself. “If you’re going to choose ambition choose it honestly with cruelty” the forest spirit later advises, and Washizu might have been more successful if had he done so earlier.

Then again, the world he lives in is as Lady Asaji describes it a wicked one in which betrayal is an all but inevitable certainty. Washizu insists that Miki is his friend, and that making Miki’s son his heir satisfies the prophecy while binding him to him so that he cannot rebel even if he were minded to. But Lady Asaji assumes that Miki is ambitious too, suggesting that he may strike first or report his treachery in the hope of personal advancement. For the prophecy to come true, someone has to betray the lord though it need not have been either of them but there can be no trust or friendship in this world of fierce hierarchy and internecine violence.

Both men should perhaps have realised that when they were trapped riding around the eerie lair of the forest spirit with its mists and cobwebs not to mention heaps of piled skeletons still in their armour all victims of ambition and the spirit’s false promises if also echoing the legacy of wartime folly. “Look upon the ruins of the castle of delusion” the noh chant that opens and closes the film intones, warning of illusionary riches and the price of deluding oneself along with the destruction wrought by those unable to break free of the spider’s web of human desire.

Throne of Blood screens at the BFI Southbank, London on 21st February 2023 as part of the Kurosawa season.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

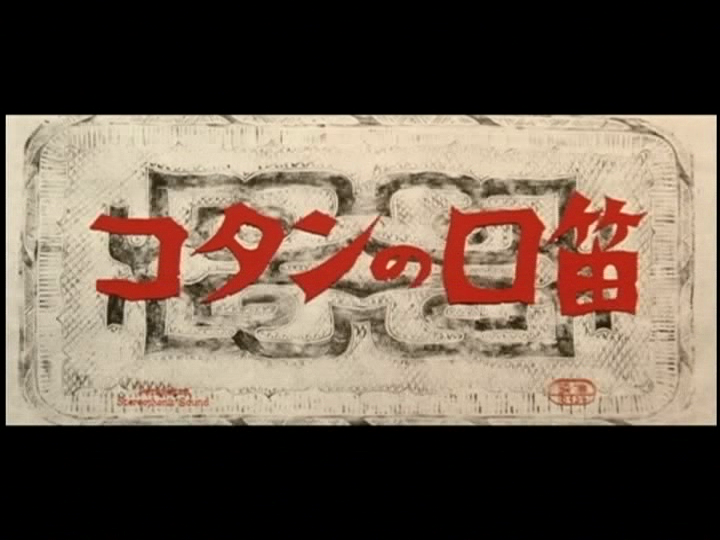

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes.

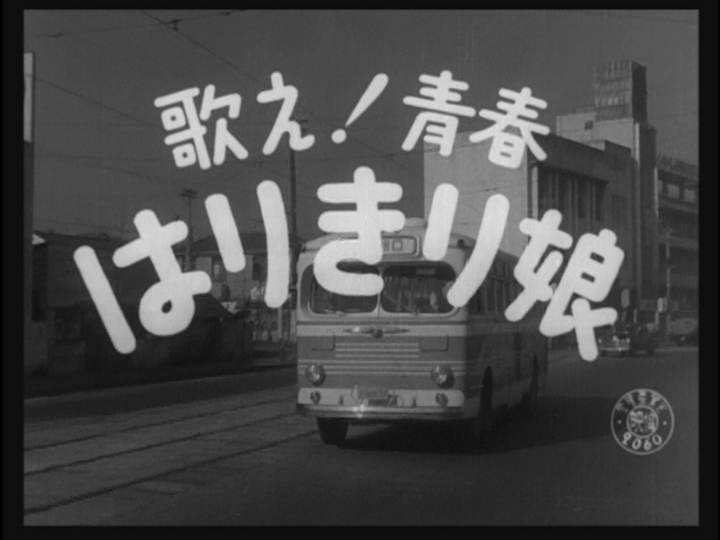

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes. Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the

Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the