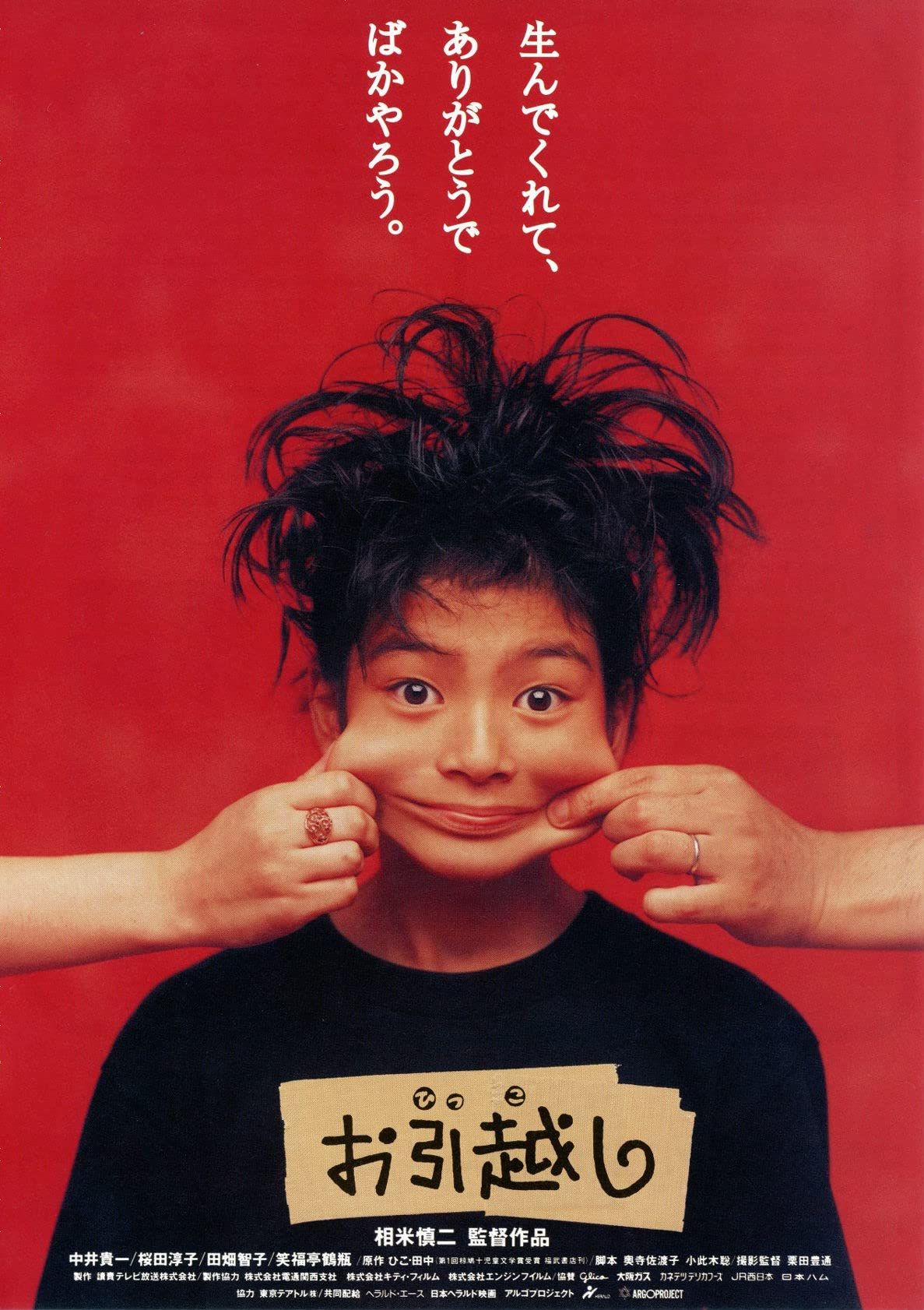

The title of Shinji Somai’s 1993 coming-of-age drama Moving (お引越し, Ohikkoshi) quite literally refers to the process of vacating one space in order to inhabit another but also to the heroine’s liminal movement into a space of adulthood while caught in the nexus of a recently destabilised society itself in a state of flux. Not only must she process the disruption of her father’s decision to leave the family home, but its wider implications that will one day leave her orphaned while coming to accept that such partings are only a part of life to borne with stoicism and sympathy.

At around 12 or so, Renko (Tomoko Tabata) finds herself on the brink of change. Not only is she beginning to grow up, soon to be changing schools, but is also facing a further destabilisation of her home as her parents prepare to separate. The tension in the household is clear from our first meeting with the family as they sit around an almost violent, green triangular table the point aimed straight at us with Renko at the opposite end and her near silent mother and father on either side. As she often will, Renko attempts to parent her parents, repeatedly criticising her father for his poor table manners wondering if he’ll be able to take care of himself when living alone while later remonstrating with her mother for having had too much to drink while cautioning her to mind what the neighbours might think.

Already unbalanced by the economic shock of the bubble bursting, the Japanese society of the early 90s was also changing evidenced in part by the separation itself. Divorce is still a minor taboo, even Renko herself had taken part in the shunning and bullying of another girl who’d transferred to their school after returning to her mother’s hometown following her parents’ separation, but this is perhaps the first era in which it becomes acceptable to end a marriage solely because one or both parties is unhappy rather than there being some additional pressure that endangers the family. “Marriage is survival of the fittest”, Renko’s mum Nazuna (Junko Sakurada) later exclaims during a heated exchange but we can also see that the marriage itself was already unusual perhaps uncomfortably suggesting an altered power balance and shifting gender roles led to its breakdown. Father Kenichi (Kiichi Nakai) had previously worked from home completing many of the domestic tasks while Nazuna had become the breadwinner with a successful career earning higher salary. She complains that when she was pregnant with Renko Kenichi sniped at her for not contributing to the household financially but changed his tune when her economic success undercut his sense of masculine pride.

Despite apparently embracing her freedom Nazuna nevertheless seems to resent Kenichi for leaving, accusing him of deserting his family while he later floats the idea of trying again but only perhaps because he is feeling the ache of the loss of the home he previously hinted suffocated him in responsibility. Meanwhile, Renko is also forced to process the fact that a family friend, Yukio (Taro Tanaka), on whom she’d had an innocent childish crush, is engaged to be married. Overhearing their conversation she also learns that his fiancée is pregnant but unsure about having the baby. Given all of these changes, she begins to wonder why it is she was born, intensely anxious in potential parental abandonment while witnessing the remaking of her home.

Yet to cure her of her anxiety Somai removes her from her environment, Renko once again taking on a parental role in borrowing her mother’s credit card to book a hotel and train tickets to a familiar destination they’d previously travelled to as a family. It’s in this liminal space that Renko begins roam, eventually encountering an old man with some important life lessons while undergoing a spiritual odyssey of her own as she weaves through a summer festival towards an ethereal encounter with her past self and the spectre of her future orphanhood. Somai’s characteristically lengthy tracking shots add to the sense of destabilisation, Renko’s world constantly in motion yet as she tells us herself she’s on her way to the future, moving on but on a more equal footing and discovering at least a sense of equilibrium in an ever shifting society.

Moving screens at the BFI on 29 December as part of BFI Japan.