A trio of actors undergo a coming-of-age tale of their own when a baby is suddenly abandoned on their doorstep in Shuichi Okita’s charming slice of life dramedy, Our Dear Don-chan (おーい!どんちゃん, Oi! Don-chan). A take on Three Men and a Baby, the film stars the director’s own daughter and follows her over a period of three years as the actors attempt to adjust to fatherhood and the new kind of family that has arisen between them.

As the film opens, Michio (Tappei Sakaguchi), Ken (Hirota Otsuka), and Gunji (Ryuta Endo) are struggling actors working in slightly different media but having about the same amount of luck and continually dejected about their lack of career success. Ironically while playing the game of life, Ken has a baby girl in the game but is surprised to hear one crying for real on the street below. On reading a note in her pushchair, Ken realises that the baby has been left by a previous girlfriend, Kaori, with the instruction that he raise it.

Of course, the situation gives rise to a degree of panic, Ken wondering not only if he is the father but if he can be while supported by the other two guys, along with former houseman Sakamoto and his girlfriend Akari, taking care of more practical matter likes getting nappies and baby food. Then again, some of the practical details are already overcome by virtue of their occupations which allow them to be home during the day taking shifts to watch the baby they christen “Don-chan” on account of not knowing her real name.

As they struggle with the demands of fatherhood, the three men each commit themselves to Don-chan’s well being, mindful of the memories she’ll make in the future and wanting to make her present as happy as possible. At one point they decide to take a camping trip in order to show her that they can be “manly dads”, but otherwise entertain her at home or take her on trips to the aquarium acting as a trio even if Ken is technically the primary dad forming a new kind of family that makes it easier to care for a small child than it might otherwise have been. If Ken had been on his own, he may not have been able to raise her. Michio and Gunji both complain at the precarious state of childcare facilities, lamenting that you can’t get a place unless you work full-time but you can’t work full-time if you can’t get childcare for when you’re at work.

Meanwhile, they continue to struggle in their professional lives. A humiliating audition for a TV commercial causes Ken to rethink his career plans, stopping off to buy new toys for Don-chan on the way home lamenting that he “danced like an idiot for no reason.” Michio continues to go full method over researching all his roles for seconds of screen time in TV and movies, while Gunji’s stage career is disrupted when the manager of his troupe decides to admit himself to a psychiatric facility for long term care. Through their interactions with Don-chan, however, they all begin to grow up gaining further life experience which enhances their performance ability and gives them a greater goal to work towards aside from mere career success.

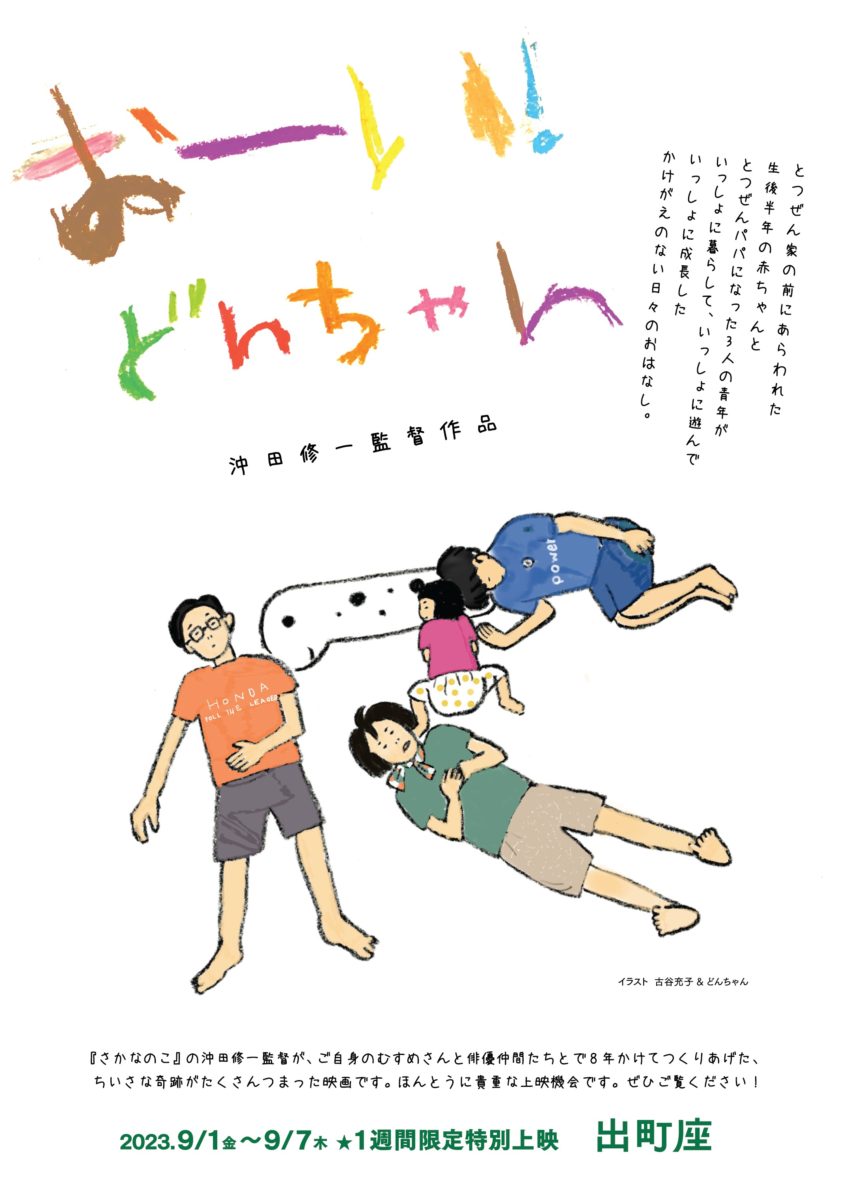

A heartwarming familial drama, the film doesn’t gloss over how difficult it can be to raise a child in contemporary Japan especially as a single-parent but rather embraces a larger idea of the word family which centres platonic friendship and community while simultaneously understanding of Kaori’s position in the knowledge that none of this is easy and she may not have had access to the kind of support that made it possible for Ken to care for Don-chan with so much love and attention. In any case, little Don-chan is certainly lucky to have so many people around her all invested in her happiness and future whose lives she has also enriched just by her existence. A truly happy film, Okita adds small doses of absurdity to the already surreal events along with a nostalgic sense of childhood comfort right down to the childish font of the film’s titles complete with corrections and crossings out that are, much like life, evidence of joyful trial and error.

Trailer (English subtitles)