Everybody’s looking for something but mostly in all the wrong places in Chen Singing’s spiritually inclined God Man Dog (流浪神狗人, Liúlàng Shén Gǒu Rén). Lonely and disaffected, Chen’s portrait of contemporary Taiwan is of an island set adrift with no clear path to the future and no reliable guides to follow. Many turn to religion, be it Eastern or Western, while others embrace consumerism or literally fight to find a way out while refusing to let those around them drag them down. Cosmic coincidence does perhaps begin to show them the way, but it’s less a matter of faith than chance as they each find opportunity to refocus and reclaim what it is they really wanted out of life.

Everybody’s looking for something but mostly in all the wrong places in Chen Singing’s spiritually inclined God Man Dog (流浪神狗人, Liúlàng Shén Gǒu Rén). Lonely and disaffected, Chen’s portrait of contemporary Taiwan is of an island set adrift with no clear path to the future and no reliable guides to follow. Many turn to religion, be it Eastern or Western, while others embrace consumerism or literally fight to find a way out while refusing to let those around them drag them down. Cosmic coincidence does perhaps begin to show them the way, but it’s less a matter of faith than chance as they each find opportunity to refocus and reclaim what it is they really wanted out of life.

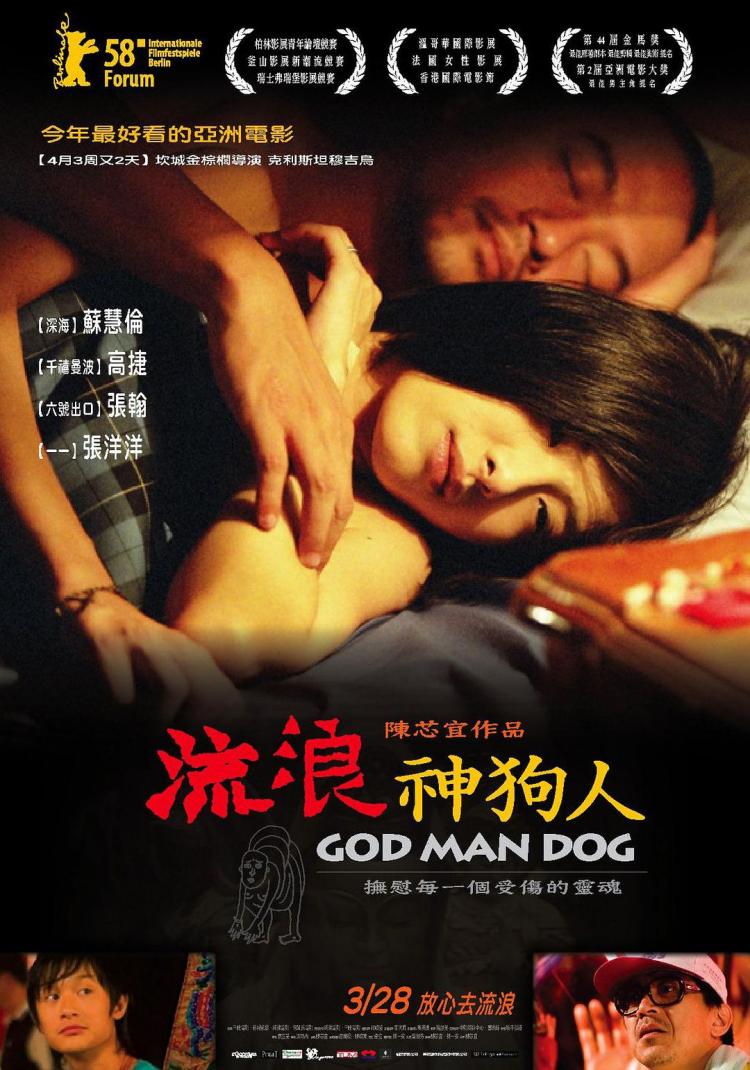

Hand model Ching (Tarcy Su) is suffering from postnatal depression after the birth of her first child but her husband, Hsuing (Chang Han), remains detached and insensitive – running off to new age country retreats to avoid the strain of caring for his delicate wife and baby daughter. Meanwhile, an indigenous couple have lost a child of their own and then suffered the departure of both their daughters because of the father’s persistent alcoholism. Their daughter, Savi (Tu Hsiao-han), is living in Taipei with a beauty obsessed friend who’s doing dodgy modelling to pay for a boob job while Savi works hard on her martial arts as a possible path out of rural poverty. A chance encounter brings her into contact with mysterious Buddha bus driver Yellow Bull (Jack Kao) who is saving money to pay for a new prosthetic leg while making a point of rescuing and reviving the many broken and abandoned Buddha statues which seem to call out to him from around the island, adopting a stray child, Xian (Jonathan Chang), in the process.

Everybody here wants something that they aren’t convinced they can have. The upper middle class couple Ching and Hsuing might seem comfortable enough but are filled with spiritual emptiness and feel trapped by conventionality. They’ve started to drift, and the baby far from bringing them together has only forced them further apart in thinly veiled mutual resentment. Hsuing refuses to play any role in caring for his daughter, or in trying to care for Ching whose dangerously deteriorating mental state seems to be receiving almost no support from family or medical personnel even when she tries to ask for it. In desperation she turns to Christianity, creating a further rift between herself and the intensely Buddhist Hsuing (not to mention his fortune telling obsessed mother).

Christianity is also a dominant force in the life of the indigenous couple who have been participating in AA meetings led by the local church in an effort to get their daughters to return though their faith is beginning to wane thanks to constant setbacks and the lingering conviction God has it in for them. Only through an improbable encounter with the Goddess of Mercy sitting beatifically on the back of Yellow Bull’s truck does the drunken father begin to wake up in making a symbolic act of sacrificial recompense in the hope of being forgiven for a transgression he did not perhaps wholly make. Guanyin, apparently, is there for them even if God was sleeping.

The indigenous couple, whose land is being infringed on by those like Hsuing who want to repurpose it to turn the beautiful natural surroundings into man made spas and thereby turn spiritual peace into a marketable commodity, tried to escape their troubles via alcohol and then turned to religion to save them from drink only to find it not quite as supportive as they’d hoped. Then again, kindly Yellow Bull stuffs his fortune telling box full of positive fortunes because, after all, people looking for fortunes are looking for hope so perhaps it’s not so much that Buddhism is “better” than Christianity, as it is that people are basically good and in the end that’s what you ought to have faith in. On the other hand, Savi and her friend end up making extra pennies through a fake dominatrix double act during which the girls rob their sleazy johns in a potentially dangerous piece of societal revenge that is, ironically, her friend’s plan to save money for a boob job to conform to those same patriarchal conventions they were just superficially rebelling against.

In any case, some kind of cosmic force eventually pulls them all together through the intervention of the many “abandoned” stray dogs who run free across the landscape, as does one supposedly million pound pedigree pup after making a break for freedom as the sole survivor of a nasty car wreck. “Freedom” might mean different things to different people at different times, but each of these lonely souls is in a sense trapped by their own sense of disconnection and the anxiety of feeling abandoned by those around them. Dogs, or maybe gods, bring them back together and accidentally reawaken their faith in themselves and each other to send them back out into the world with slightly lighter hearts if in acceptance more than hope.

God Man Dog was screened as part of the Taiwan Film Festival UK 2019. Also available on DVD in the UK courtesy of Terracotta Distribution.

UK Terracotta release trailer (English subtitles)