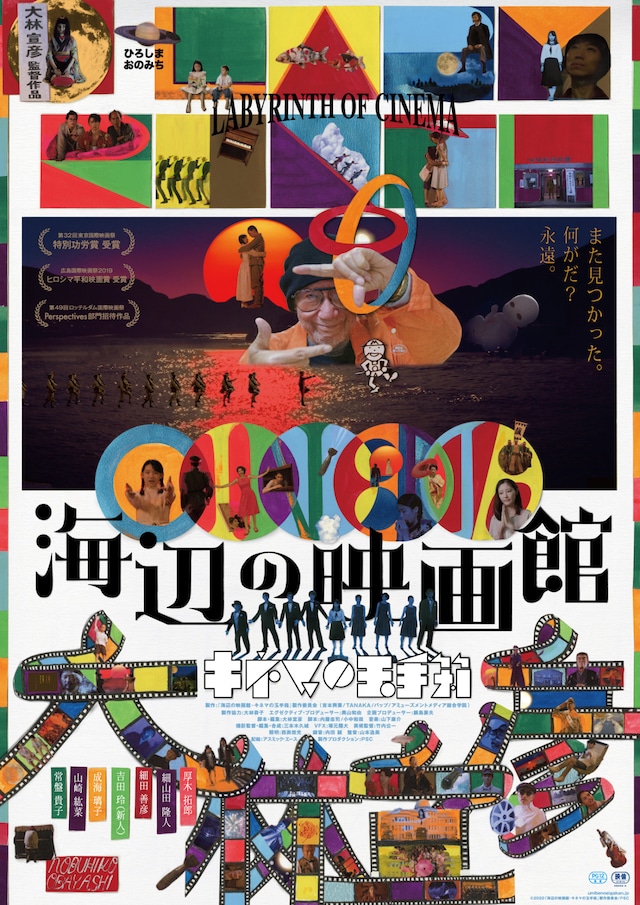

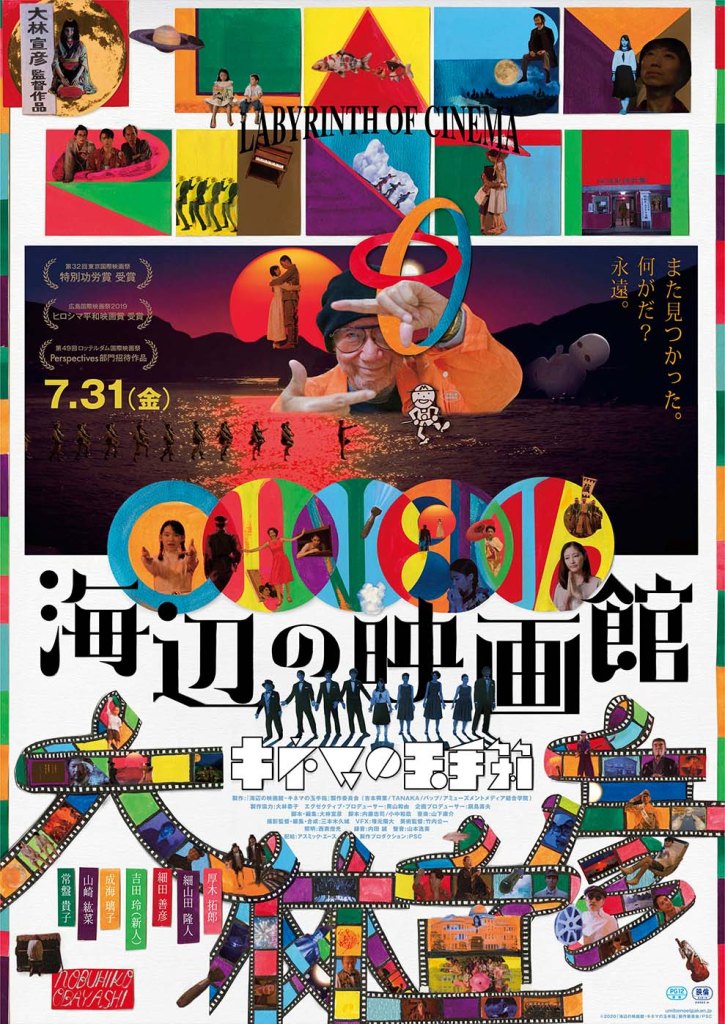

“A movie can change the future, if not the past” according to the newly reawakened youngsters at the centre of Nobuhiko Obayashi’s final feature, Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館-キネマの玉手箱, Umibe no Eigakan – Kinema no Tamatebako). Continuing the themes present in Hanagatami, Labyrinth of Cinema takes us on a dark and twisting journey through the history of warfare in Japan as mediated by the movies with the poet Chuya Nakahara as our absent prophet reminding us that “dark clouds gather behind humanity” but that we need not feel as powerless as Nakahara once did for there are things to which our hands can turn.

As the intergalactic narrator, Fanta G (Yukihiro Takahashi), explains the “present” of this film is our own but we find ourselves once again in Obayashi’s hometown of Onomichi where the local cinema is about to play its final show, a programme dedicated to the war films of Japan. Torrential rain has ensured a good audience, including three variously interested young men – cinephile Mario Baba (Takuro Atsuki), monk’s son Shigure (Yoshihiko Hosoda) who fancies himself a Showa-era yakuza, and “film history maniac” Hosuke (Takahito Hosoyamada). Noriko (Rei Yoshida), a teenage girl in sailor suit who only appears in blue-tinted monochrome, opens the show with a ‘40s folksong but soon disappears into the screen, followed by the three men who become the guardians and protectors of her image as they attempt to safeguard her existence through various scenes of historical carnage.

Noriko, the embodiment of a more innocent Japan, insists that “all you need is movies” and that she wants them to teach her of the things she does not know, most pressingly the nature of war. She enters the movies to find out who she is as we too peek into the soul of the nation, spinning back to the years of peace under the Tokugawa shogunate later juxtaposed with those of wartime nationalism in which “overseas” had become synonymous with adventure and opportunity, if perhaps darkly so in enabling the advance of Japanese imperialism.

The three heroes find themselves literally immersed in cinema, pulled in by the great empathy machine to experience for themselves that which they could only previously imagine. Yet like the narrator of Nakahara’s poem they find themselves powerless, defined by their status as “members of the audience” even as their identities begin to blur with those of the various protagonists with whom they are being asked to identify. They attempt to protect the image of Noriko wherever they find her, even as a young Chinese woman orphaned by Japanese atrocity, but largely fail, unable to alter the course of history as mere spectators bound by the narrative rules of cinema.

Yet sitting in front of the cinema screen convinces them that “movies demand I do something with my life”. Fanta G explains away the Meiji-era mentality with the claim that “people in power always punish freedom with death”, concluding that one man cannot change the system in the various assassinations of the revolutionaries trying to determine the future course of a nation, but insists on the right of all to be free to live their present and their future. The men learn that though they are powerless in the face of history, they have the power to craft their own happy ending but only if they abandon their identities as “members of the audience” in the knowledge that “if we just watch nothing will change”.

With a deliberately theatrical artifice, trademark colour play, and surrealist imagery Obayashi wanders through 100 years of Japanese cinema with jidaigeki silents giving way to Masahiro Makino musicals and they in turn to the Hollywood-influenced song and dance of the immediate post-war era which was itself in the eyes of Fanta G an attempt to avert ones eyes from the horrors of the recent past but also a “lie” which carried its own kind of truth. The image of “Noriko” remains burned into the cinema screen, the movies the sole repository of the soul of Japan, though perhaps a Japan which no longer knows itself. “As long as I remember you, you’ll live” another bystander claims, “that’s why I have to be here”, waiting in a movie theatre existing outside of time and home to the labyrinths of cinema in which are to be found the vaults of human empathy. “To young people who want a future where no one knows wars, we dedicate this movie with blessing and envy”, run the closing lines, “in order to achieve world peace there are many things our hands can turn to” if only we rediscover the will to turn them.

Labyrinth of Cinema is available to stream in the US until July 30 as part of this year’s Japan Cuts.

Original trailer (English subtitles)