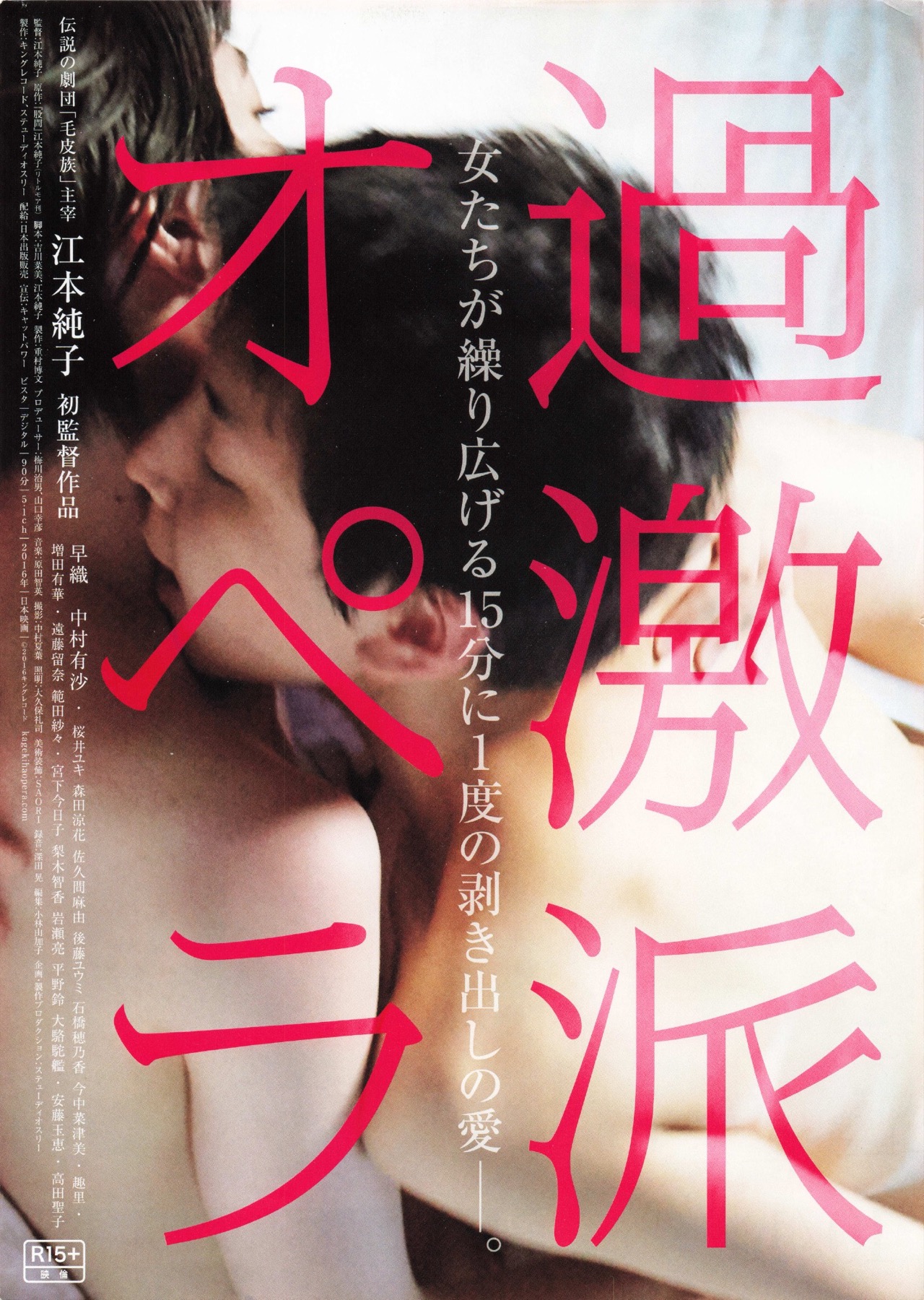

Junko Emoto ironically explores Tokyo’s fringe theatre scene in adapting her semi-biographical novel. Shot with a roving, handheld camera, The Extremists’ Opera (過激派オペラ, Kagekiha Opera) situates itself within an all female, avant-garde experimental theatre company but quickly makes plain that even those with high-minded artistic intentions are not free of the usual human flaws as the borderline abusive, womanising female director finds herself sabotaging everything she’s built through a mix of hubris and wandering desire.

Blanket Cult are a popular company on the fringe theatre scene with a small following devoted to their art. Former banker Ayako bursts into their office determined on an audition and subsequent career change precisely because she can’t get enough of director/playwright Nao’s experimental plays which, she explains, she believes can stop wars. Nevertheless, it’s not Ayako the team are struck by, but the intense young woman who came in behind her, Haru, who more or less demands to be taken on. Nao is captivated, hiring both women on the spot and vowing to write a new piece with Haru in the lead. Of course, she does this partly for not altogether altruistic reasons. Immediately after the first script meeting she asks Haru to stay behind and then propositions her, directly declaring her love with the justification that she’d rather be upfront rather than waste time during the rehearsal process. Haru tells her that she’s not into women, but Nao doesn’t take no for an answer seemingly oblivious to the fact that what she’s doing is harassment and really she’s no better than any other sleazy male director handing out parts to women she wants to sleep with.

Nevertheless, her persistence even with its undignified pleading eventually pays off. Haru relents, either because she’s fed up of fending off Nao’s advances or discovering that she is on some level receptive, finding that she does in fact enjoy sex with another woman. She agrees to start dating Nao who declares Haru her muse and the pair move in together but their relationship is threatened by their working environment with its petty jealousies and temptations. Emoto opens the film with a graphic sex scene of two naked women 69-ing, rolling around in the empty environment of the garage the troupe uses to rehearse. The two women are Nao and her previous squeeze, a former leading lady she throws over because of her attraction to Haru whose own desire is perhaps signposted after she walks in on them going for a second round and makes a passive aggressive scene that leads the other woman to warn her that Nao is a heartless womaniser with a habit of bedding her leading ladies, sometimes in the wings.

Yet it’s not only Nao’s misplaced desire that endangers the troupe but her arrogance and abusive directing style. After their play proves a success, she unwisely gives in to ambition and sells out by allowing a mainstream professional actress, Yurie, to join the troupe, a move which disrupts their dynamic while also inflaming Haru’s jealousy as she begins to wonder if she’s already being replaced. Nao snaps at her team and stops giving them proper direction in favour thinly veiled insults. She repeatedly instructs an actress to lose weight while increasingly allowing Yurie to dominate the rehearsals, accepting all of her ideas even while the other members sceptical. She even goes so far as to abandon her usual thriftiness, purchasing elaborate props such as a large vertical tank which leads her into another possibly inappropriate relationship with an older woman who had been pursuing her. Needless to say, the whole thing blows up in her face, ruining not just her relationship with Haru but that with her theatre company who are now all thoroughly fed up with her mistreatment and have entirely lost respect for her as a person and an artist.

“If you want to pick a fight with society live in it first,” her benefactor irritatedly tells Nao after she’s thoughtlessly caused offence, reminding her that she lives in a kind of bubble that is the fringe theatre scene. Her only real interaction with someone outside of it is with the estate agent who finds her and Haru a flat and is extremely confused as to why they only need one room if they’ll be living together, concerned that female roommates are a liability because sooner or later one gets a boyfriend and leaves the other in the lurch unable to make the rent alone. Unable to learn her lesson, Nao has furiously energetic sex with an apparently wealthy starstruck fan and then immediately asks for money, perhaps getting a taste of her own medicine when she assures her there’s plenty more where that came from as long as she sees her again and also gives her a part in a play. Playfully ironic with its whimsical score and slightly detached gaze, Emoto’s refreshingly explicit drama is both a mild satire of the avant-garde fringe theatre scene and a takedown of its self-involved director whose inability to separate the creative from the carnal proves her downfall both artistic and emotional.

Trailer (English subtitles)