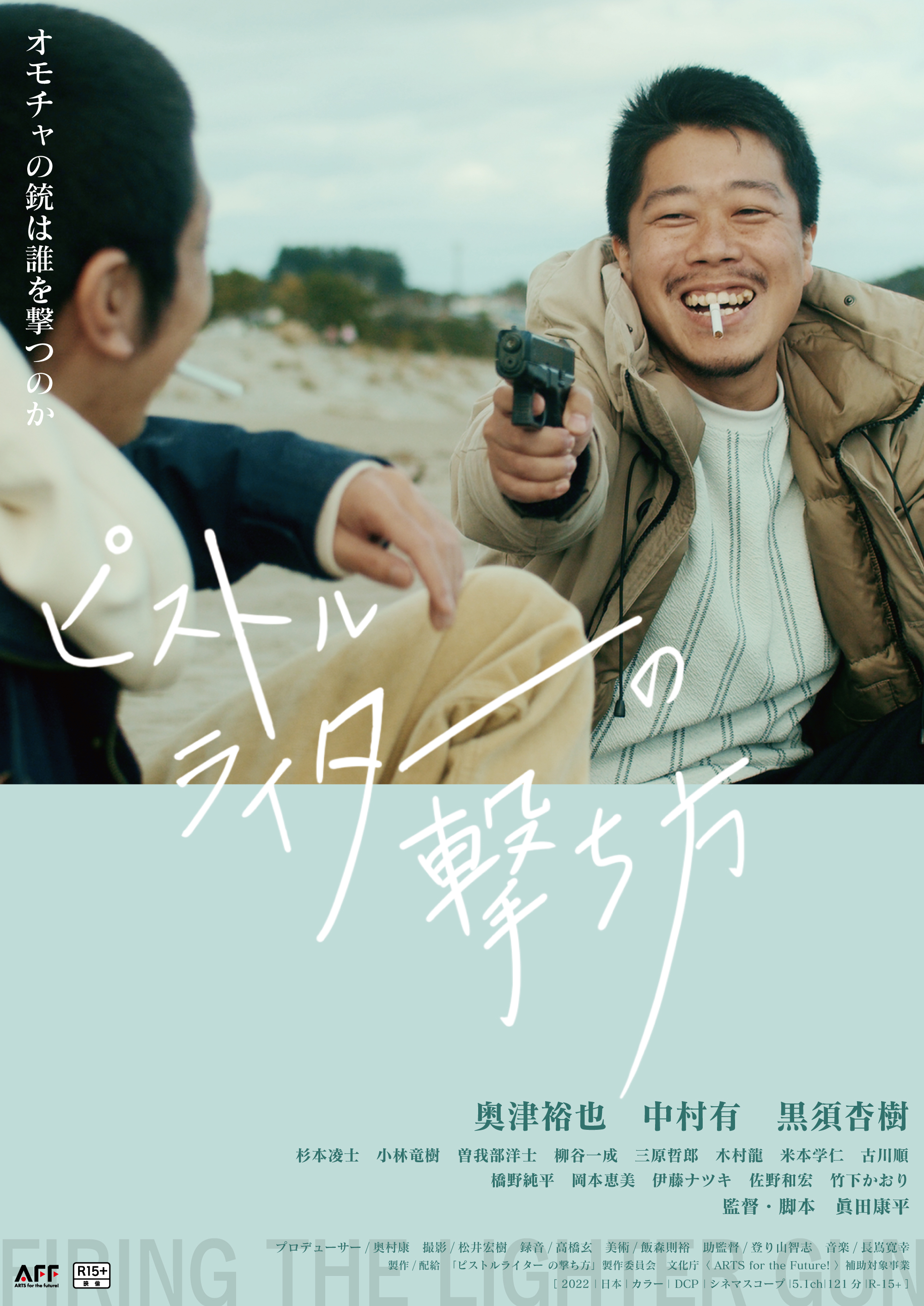

“Whatever got you here, it can’t be any good” a resident of a flophouse reflects on their moribund circumstances suckered to into debt bondage by exploitative yakuza who force them to risk their lives doing clean up in a nuclear exclusion zone. Kohei Sanada’s bleak indie drama Firing the Lighter Gun (ピストルライター の撃ち方, Pistol Lighter no Uchikata) takes place after second nuclear disaster has left even more of the land unsurvivable. The heroes have been quite literally displaced, left without a place to return to or call a home, but are also emotionally alienated unable to envisage an escape for themselves from this otherwise hopeless existence.

Having recently been released from prison, Ryo (Yu Nakamura) remarks that the area has changed since he’s been away but his friend Tatsuya (Yuya Okutsu) counters that he doesn’t really think so. In any case, Tatsuya lives with a huge inferiority complex most evident on his attendance at a school reunion he didn’t want to go to where he sits sullen and dejected among those who’ve moved up in the world not least his ex, Shoko (Emi Okamura), who left him for a guy with a steady government job but still drops by to care for his ageing mother who suffers from dementia and the legacy of domestic abuse. Tatsuya is not a yakuza but his work is yakuza adjacent in that he drives a van full of equally hopeless men recruited for a dodgy operation offering cleanup services in the nuclear exclusion zone.

Though the jobs are supposed to pay well with a bonus for the hazardous nature of the work, most of it is being skimmed by the yakuza bosses who deduct vast amounts from the men’s pay-packets for “expenses” such as the right to sleep in a communal flophouse where they charge them exorbitant amounts for snacks and drinks which they have to buy because they aren’t allowed to go out. Nor are they allowed to quit the job, trying to run incurs a 50,000 yen fine on top of any debts they’re supposed to be working off. An unexpected addition to Tatsuya’s van one day is Mari (Anju Kurosu), a sex worker, who’s been forced to work for the gang to pay off a debt incurred by an ex who’s since run off.

As she later says, it’s a waste of time dreaming about a home, life is easier when you no longer expect one. But despite themselves a gentle bond soon arises among the trio of dispossessed youngsters who each feel trapped by their circumstances but are uncertain if they still have the strength to contemplate escape. Tatsuya’s sense of impotence is embodied by the cigarette lighter he carries around which is shaped like a pistol and realistic enough to cause a yakuza bodyguard a moment of concern but of course of no real use to him. As Ryo puts it, Tatsuya’s problem is that he still cares about those around him and is not heartless enough to treat the flophouse men like the “disposable tools” others regard them to be. He is constantly belittled by grinning boss Takiguchi (Ryoji Sugimoto) who blames him for everything that goes wrong and calls him useless and ineffectual, while the flophouse boss also regards him as soft for refusing to beat one of the men who had tried to escape.

Ryo meanwhile swings in the opposite direction, giving in to a sense of hopelessness that sees him shift towards yakuza violence but perhaps eventually allows him to bounce back and take a chance on escape even if it maybe short-lived or spent in constant hiding. Tatsuya may feel trapped by responsibility to his mother, but is otherwise psychologically unable to move forward staking all his hopes on the rumour of a new power plant hoping it will ignite the town in the way the construction of the last one did despite knowing its attendant risks. Unlike Ryo, he says there’s no point in running, despite himself still yearning for a home. The flophouse men are no different, the few who escape are soon drawn back to other similar kinds of work because there is no other hope for them. Still, once the final shots have been fired there is a kind of clearing of the air and the light of a new dawn even if few seem to be able to see it.

Firing The Lighter Gun screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Original trailer (no subtitles)