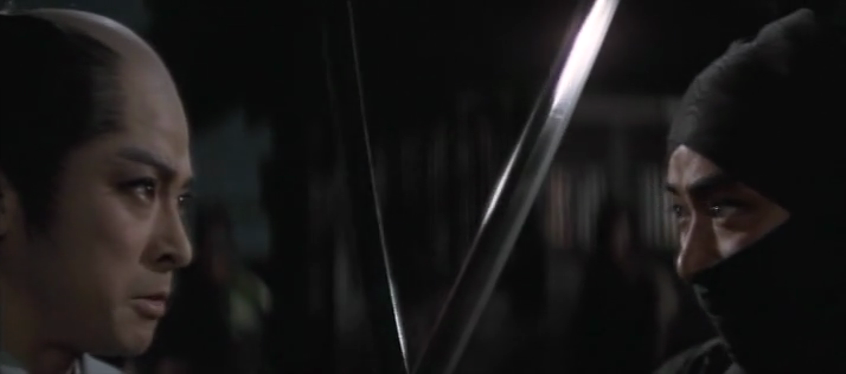

A bunch of corrupt monks get a lesson in business ethics from one of their own in the aptly titled Wicked Priest (極悪坊主, Gokuaku Bozu). The first in a series of five films starring Tomisaburo Wakayama as a rogue Buddhist monk who enjoys fighting, drinking, and women but deep down has a powerful sense of moral righteousness, Wicked Priest is in its own way another take on classic ninkyo only this time it’s temples acting like yakuza clans rather than actual gangsters with “wicked priest” Shinkai the ironic symbol of nobility.

Set in early Taisho, the film opens with a prologue set five years before the main action in which Shinkai breaks up a fight between another violent monk, Ryotatsu (an incredibly gaunt Bunta Sugawara), and some yakuza he challenged while they were hassling a young man for supposedly messing with the wrong girl. Predictably, it’s Shinkai who ends up in trouble. Relieved of his duties, he’s exiled to another temple and sentenced to spend a whole year in isolation thinking about what he’s done. Five years later we can see that the conclusion he’s mostly come to is that the religious world is full of hypocrisy anyway and he might as well live his life to the full while he can.

Indeed, the opening scene sees him ironically reciting a sutra with his head between a woman’s legs and preparing to drink holy water from her belly button. The problem here seems to be one of inter-temple politics that sees Shinkai hassled by officious monk Gyotoku (Hosei Komatsu) who objects to Shinkai’s behaviour and to the leniency which is shown to him by head priest Donen (Kenjiro Ishiyama). Of course Gyotoku is later discovered to be the source of corruption, wanting to depose Donen and take control of the temple in part to facilitate a sex ring he’s running that involves live peep shows literally on temple grounds. Shinkai, meanwhile, has a particular dislike for abusers of women and especially for pimps eventually rescuing some of the women indentured by a local brothel and unfairly kept on after redeeming their contracts with bogus loans, and starting a women’s refuge in the temple where they can find “honest” work and eventually lead “normal lives” as farmers or waitresses free of the abuse and oppression they faced in the “hell” of indentured sex work.

Wandering around the town, he saves one young woman newly arrived in Tokyo from falling victim to a scam and being forced into sex work by getting her a waitressing job at a local restaurant. To keep her safe, he jokes with the cafe owner that he’s already slept with her which in the bro codes of the time makes her his woman and owing to his famously violent nature no one else is going to bother her. For what it’s worth, women young and old come to admire him greatly for his gallantry though he never abuses his position. All of his sex partners are at least of his own age and fully consenting even if he is not exactly faithful in love.

Meanwhile there’s some minor commentary more familiar from post-war gangster films that sees the temple as a refuge for orphaned men. The fatherless Shinkai finds a beneficent paternal authority in Donen and is, he says, “reformed”, if living to a code that seems to be mostly his own but informed by a kind of moral righteousness not found in others at the temple. Having discovered that a wayward young man Shinkai is attempting to save from his life of petty crime exploiting women for his own gain is a son he never knew existed, Donen would have left the temple to fulfil his familial role but is prevented from doing so by the intrusion of temple politics. Unless undertaking specific vows, Buddhist priests are not necessarily expected to practice celibacy and are permitted to marry yet Donen’s father objected to his choice of bride and she left not wanting to disrupt his temple career. Shinkai entrusts the boy to Donen, talking him into accepting a new paternal authority as a means of returning him to the “proper” path while himself swearing that he will leave the temple in order to ensure justice is served against the true “wicked priest” Gyotoku. Directed by ninkyo specialist Kiyoshi Saeki, the film ends in an outburst of bloody violence as Shinkai takes revenge on institutional corruption but once again leaves its hero a lonely wanderer in an unjust world.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.