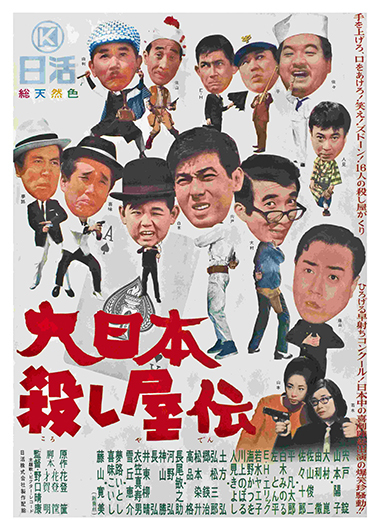

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.

After the amusing Bond style opening, we witness the first victim of Joe of Spades who happens to be one of the five top gangsters in town. Sure enough, the other four then receive a threatening phone call to the effect that they’re next in line for a bullet in the brain. After ringing up an assassins agency and holding a series of auditions, the head honchos wind up with a gang of hitmen bodyguards each of whom have their own theme and wacky back story.

The leader of the gang is Heine Maki – a poetry loving, bowler hatted killer whose signature weapon is a heavy book of poems with a gun hidden inside,. He’s joined by O.N. Kane – an ex-baseball player who missed out on the major leagues through being too good and carries a baseball bat that’s really a gun, “Knife” Tatsu – ex-sushi chef knife thrower with an intense fear of fish, Al Capone III – a midget who claims to be the Japanese grandson of Al Capone and is obsessed with the Untouchables TV show, and of course Komatsu himself whose signature move is to throw his abacus in the air and invite chaos in the process.

The guys are really a little more than this small town can handle though they quickly discover the situation is nowhere near as straightforward as they thought and wind up facing off against some equally eccentric foes. That’s not to mention the mama-san at Bar Joker who turns out to be at the center of the case and a local mechanic who’s suspiciously handy with a pistol.

There really are no words to describe the quick fire, extremely zany universe in which Murder Unincorporated takes place. This is a world ruled by crime in which each of our “heroes” showcase extremely sad backstories which explain why they had absolutely no choice but to turn to killing people to survive. Take “Knife” Tatsu for example, he became a hitman because he was unable to kill the fish gasping away on his cutting board so he decided to kill people instead. O.N. Kane turned murderous after being let down in his baseball dream, Heine has a romantic tale of lost love, Capone III simply has it in the blood, and Komatsu? He wants to be a pharmacist…

This is all inspired by legendary Japanese funnyman Kobako Hanato who is famous for his Southern Japan flavoured absurd comedy routines. Kon Ohmura, who plays Komatsu, was one of his top collaborators for a time and became one of Japan’s all time great comedians. Meta quips such as remarking that the police are about to turn up “for the first time in this film” and involved jokes like the one that sees Komatsu tracking down identical “Joes” in varieties club, diamond, heart (amusingly, dressed as a geisha and playing pachinko), before heading into a punchline it would be a crime to spoil only add to the feeling that absolutely anything could happen and that would be perfectly OK.

Director Noguchi mostly keeps things straightforward but builds a fantastic comedic rhythm managing the quick fire dialogue and general absurdity with ease. Much of the film is told in flashback or reverie but the device never becomes old so much as easily syncing with with general tone of the film. There are some more unusual sequences such the opening itself, keyhole view, and a later sequence where we see directly though Komatsu’s big square glasses but otherwise the deadpan filming approach boosts the inherent comedy in the increasingly surreal situations. Quirky, oddly innocent, absurd, and just extremely laugh out loud funny, Murder Unincorporated is a world away from Nikkatsu’s po-faced crime dramas but exists in a crazy cartoon world all of its own that proves near impossible to resist!

Murder Unincorporated is the third and final film included in the second volume of Arrow’s Nikkatsu Diamond Guys box set.

The bright and shining post-war world – it’s a grand place to be young and fancy free! Or so movies like Tokyo Mighty Guy (東京の暴れん坊, Tokyo no Abarembo) would have you believe. Casting one of Nikkatsu’s tentpole stars, Akira Kobayshi, in the lead, Buichi Saito’s Tokyo Mighty Guy is, like previous Kobayashi/Saito collaboration

The bright and shining post-war world – it’s a grand place to be young and fancy free! Or so movies like Tokyo Mighty Guy (東京の暴れん坊, Tokyo no Abarembo) would have you believe. Casting one of Nikkatsu’s tentpole stars, Akira Kobayshi, in the lead, Buichi Saito’s Tokyo Mighty Guy is, like previous Kobayashi/Saito collaboration

Sometimes, just like an aimless drifter wandering into town, you feel as if you’ve come in during the second reel and missed some vital piece of information leaving you feeling a little at odds with the current situation. So it is with Buichi Saito’s The Rambling Guitarist (ギターを持った渡り鳥, Guitar wo Motta Wataridori) which is, apparently, the first film in a series though feels a little more like the second.

Sometimes, just like an aimless drifter wandering into town, you feel as if you’ve come in during the second reel and missed some vital piece of information leaving you feeling a little at odds with the current situation. So it is with Buichi Saito’s The Rambling Guitarist (ギターを持った渡り鳥, Guitar wo Motta Wataridori) which is, apparently, the first film in a series though feels a little more like the second. Loosely inspired by Julian Duvivier’s 1937 gangster movie Pépé le Moko, Toshio Masuda’s Red Pier (赤い波止場, Akai Hatoba) was designed as a vehicle for Nikkatsu’s rising star of the time, Yujiro Ishihara – later to become the icon of the Sun Tribe generation. On paper it sounds like a fairly conventional plot – young turk of a gangster comes to town to off a guy, sees said guy killed in an “accident”, and shrugs it off as one of life’s little ironies only to accidentally become acquainted with and fall head over heals for the dead guy’s sister. So far, so film noir yet Masuda adds enough of his own characteristic touches to keep things interesting.

Loosely inspired by Julian Duvivier’s 1937 gangster movie Pépé le Moko, Toshio Masuda’s Red Pier (赤い波止場, Akai Hatoba) was designed as a vehicle for Nikkatsu’s rising star of the time, Yujiro Ishihara – later to become the icon of the Sun Tribe generation. On paper it sounds like a fairly conventional plot – young turk of a gangster comes to town to off a guy, sees said guy killed in an “accident”, and shrugs it off as one of life’s little ironies only to accidentally become acquainted with and fall head over heals for the dead guy’s sister. So far, so film noir yet Masuda adds enough of his own characteristic touches to keep things interesting.