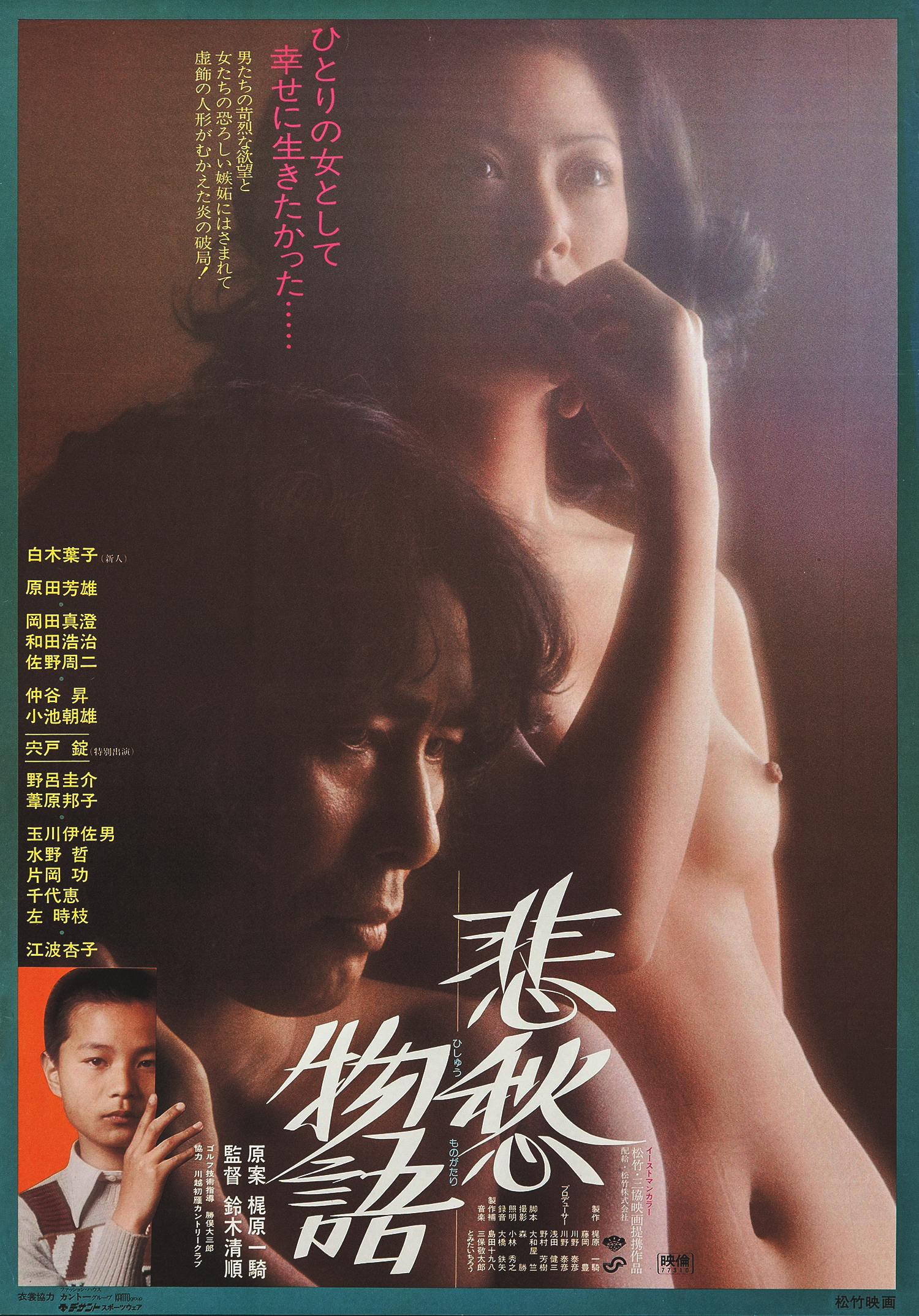

Famously, Seijun Suzuki was let go by Nikkatsu in 1968 after studio bosses became fed up with his apparently “nonsensical” filmmaking. Exiled from the film world, Suzuki made do with TV work before making his comeback with, rather surprisingly, a media satire based on a manga by Ashita no Joe’s Ikki Kajiwara. A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness (悲愁物語, Hishu Monogatari) is at once a dissection of the fluctuating class and social systems of a nation entering an era of high prosperity and a condemnation of the consumerist corruptions of a society increasingly ruled by celebrity.

It is in the corporate that the corruption begins. With mild overtones of cold war paranoia, Nichei Fabrics is alarmed that a rival firm has brought on a top Russian gymnast as a brand ambassador and is convinced they need to find someone who can steal her thunder. Fashion co-ordinator Tadokoro (Masumi Okada) comes to the conclusion that they need a homegrown star and decides to make one by grooming a promising lady golfer to become both a champion and a minor celebrity after achieving an underdog victory in a prestigious tournament.

One might ask weather society at large is likely to take much interest in who wins the Japanese Women’s Golf Tournament, but then everyone loves an underdog victory and Tadokoro seems to think he can make them care through carefully managed media manipulation. Golf is also, of course, thought of as an upperclass pursuit beloved by a new class of salaryman despite its origins, as sportswriter Miyake (Yoshio Harada) describes them, as a pastime invented by farmers to stave off boredom. Reiko (Yoko Shiraki), Miyake’s girlfriend whom he is in a way agreeing to sell to Tadokoro, is ostensibly a working class woman raising her orphaned little brother who discovered a natural talent for golf while working as a caddy for veteran male golfer, Takagi (Shuji Sano), now her mentor. She is not, however, a natural media star, something not helped by the brand’s decision to photograph her wearing wedge shoes and eventually a bikini on the green to showcase their leisurewear which she otherwise would not necessarily be wearing during a regular golfing tournament.

The colour green ironically becomes a kind of harbinger of doom, caught in the reflection of psychotic stalker housewife Kayo (Kyoko Enami) and later that of Reiko herself while she is otherwise offered sickly green cocktails or projected against predominantly green backgrounds. The house that Nichiei build for her comes with a tiny putting green that more resembles the catwalk it eventually becomes in the crazed bacchanal organised by Kayo in which she orders the other neighbourhood housewives to strip a near catatonic Reiko of the few clothes she is still permitted to wear. The early photo shoot marked the beginning of a gradual erasure of her identity and its replacement by Reiko the star, to Tadokoro, and Reiko the champion golfer to Miyake.

Much of Reiko’s golfing technique seems to centre on a kind of cosmic ordering, insisting that she is one with the ball which will land exactly where she envisages it while ignoring her competitor’s attempts to make conversation with her warning that a golfer’s career is long and it’s a bad idea to offend ones seniors. A moment with her stylist is chilling its similarity as she’s told to believe herself happy so that she can smile for the cameras with the otherwise vacant look of a manufactured celebrity. She repeats these mantras to herself constantly even as her own personality is overwritten in part by Nichei fabrics and in part by Kayo who jumps in front of her car while Miyake is driving and thereafter blackmails her into almost total servitude.

The other housewives had objected to Reiko’s presence in describing her as “low-class” and suggesting that she must be some man’s mistress because it seems unlikely to them that a pro golfer could earn the kind of money to buy a house in their neighbourhood. Their opinion of her is confirmed in their complaints about her noisy garage door, though in truth Reiko doesn’t own the house it almost owns her given that it is provided for her by Nichiei so she can get to the studio to film the daytime show they’ve created for her which mainly seems to be about fashion rather than golf which she now has almost no time to practice despite Tadokoro’s plan for her to participate in a high profile contest against a top American golfer. A classic curtain twitcher, Kayo is taken with the idea of having a celerity living next door and, already ostracised by the other housewives for being a little odd, worms her way into her life eventually deriving a quasi-sexual thrill in being able to manipulate a famous face. “I’m the only one who knows her hair’s not real!” she squeals watching Reiko on TV with her new wig after hacking her hair off as a means of punishment for hitting her with the car.

Kayo might be, in another way, the true victim of this system. Her life is obviously materially comfortable, but she’s trapped in the role of the conventional housewife while largely ignored by her salaryman husband and, as they have no children, left on her own all day with nothing to do. When she tells Reiko that she’s lonely and just wants a friend, it goes someway to explaining her otherwise bizarre behaviour as it also does for Reiko who later chuckles when Kayo randomly asks her to sleep with her husband as a favour replying that’s it’s fine “because we’re friends”. Reiko’s body, often caught by Suzuki naked in classical poses, is misused by just about everyone from Kayo to Nichei to Miyake, leaving her little more than a grinning mannequin completely hollowed out and devoid of all individuality.

In some ways, Kayo’s decision to invite the neighbourhood women into Reiko’s home, letting them try on her clothes, drink her booze, and generally jump all over her nice new life, could be seen as an attack on everything she represents by these otherwise conservative women who resent her class transgression and independent success. Yet it’s also a very personal act of self-destruction in erasing this image of herself through that of Reiko which she has equally created. It’s another kind of self-destruction that ends the film and may be another kind of bid for freedom, an attempt to free Reiko from psychological disintegration at the hands of the consumerist society until it all quite literally goes up in smoke. A tale of sorrow and sadness indeed, Reiko is eventually consumed by the consumerist society, a little ball hit into its hole and unable to climb out, while the flames rise all around her.

A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness Japan Society New York on Feb. 11 as part of the Seijun Suzuki Centennial.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Looking from the outside in, the Tokyo of 1960 seems to have been one of rising economic prosperity in which post-war anxiety was beginning to transition into a relentless surge towards modernity, but there also seems to have been a mild preoccupation with the various dangers that same modernity might present. Like

Looking from the outside in, the Tokyo of 1960 seems to have been one of rising economic prosperity in which post-war anxiety was beginning to transition into a relentless surge towards modernity, but there also seems to have been a mild preoccupation with the various dangers that same modernity might present. Like