Perhaps overlooked in comparison with his better known contemporaries, Toshio Masuda was a bankable talent at Nikkatsu directing some of the studio’s biggest box office hits largely thanks to his long association with tentpole star Yujiro Ishihara. Nine years on from their collaborative debut Rusty Knife, however, times had perhaps begun to change. Featuring vibrant colour production design by Tokyo Drifter’s Takeo Kimura, a frequent Seijun Suzuki collaborator, 1967’s Velvet Hustler (紅の流れ星, Kurenai no Nagareboshi, AKA Like a Shooting Star) is a reworking of Masuda’s own Red Pier, itself inspired by Julien Duvivier’s 1937 French thriller Pepé le Moko, with Tetsuya Watari in the role originally filled by Ishihara. Apparently drawing inspiration from Godard’s Breathless, Velvet Hustler is a thoroughly post-modern retake, a parodic tale of gangster ennui and post-war emptiness in which rising economic prosperity has brought with it only despair.

When we first meet petty gangster Goro (Tetsuya Watari), he’s coolly standing by, leaning on a fencepost like a bored gunslinger as he waits for the perfect getaway vehicle. Jumping into a fancy red convertible which it seems has already been stolen by the young man who parked it in this packed car park, the wires handily hanging striped and exposed, Goro barrels along the highway and and performs an infinitely efficient drive-by shooting on a rival gang boss. According to the man who hired him, Goro was only supposed to cause serious injury, not death, but as he points out if the guy insists on dying that’s hardly his problem. Taking his paycheque, Goro agrees to lie low in Kobe for the next six months after which his boss will come and get him. A year later, however, and he’s still there doing not much of anything, hanging out with the local kids and acting as a procurer dragging sailors on shore leave into gang-run clubs where Americans get into fights with Vietnamese émigrés. So desperate for escape are they that Goro’s underling even suggests they go to war, later thinking better of it when he remembers seeing horrific photos from the front.

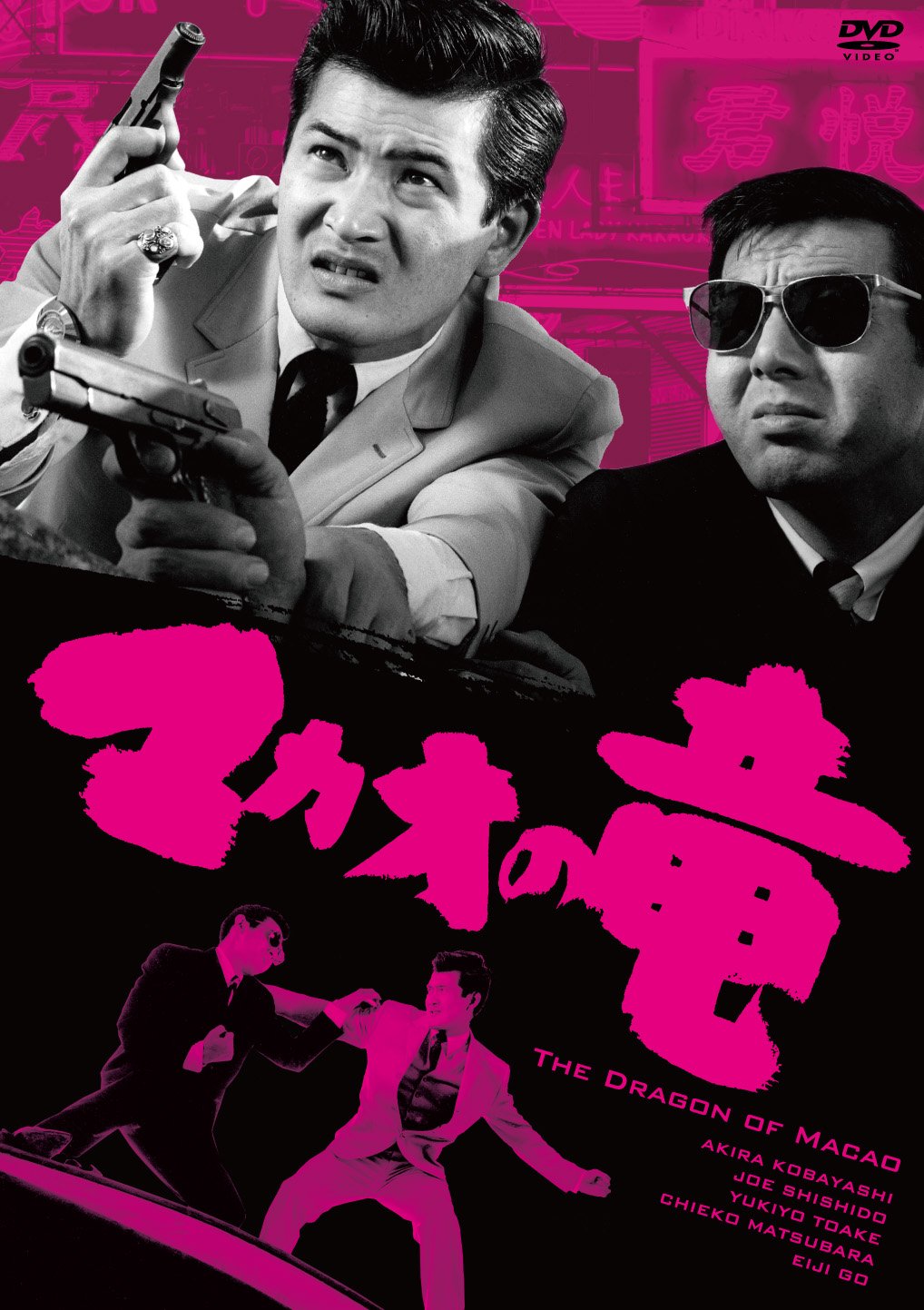

In a convenient but unsatisfying relationship with bar hostess Yukari (Kayo Matsuo), Goro explains that it’s not that he doesn’t like her, but he’s bored, “bored with fooling around with women”, but also of the business of living. The sun comes up, the sun goes down, and then it comes up again, every day all the same. His life has become completely meaningless and he has no idea what to do about it. He longs to go back to Tokyo, but is trapped in this strange Kobe limbo land, an end of the line sea port in which there is ironically no sense of escape. He doesn’t know it yet, but there’s a killer (Jo Shishido) on his trail, a killer who eventually reminds Goro that even if he kills him first another man will come. The bullets you fire are aimed squarely at yourself, Goro’s destiny is already set. There is only one way out of Kobe and it doesn’t lead back to Tokyo.

Meanwhile, another possibility presents itself in the beautiful Keiko (Ruriko Asaoka), a temporary visitor from the capital looking for her missing fiancé presumed to have done a bunk with her father’s money. Keiko is a distinctly cool yet self-assured figure, generating an instant connection with the affable gangster at once reassured by a sympathetic mama-san that Goro is good but also warned that he’s still a yakuza and as such no good for a smart young woman like her. Keiko thinks that Tokyo is pretentious and boring, confused by Goro’s insistence on getting back there but like him perhaps in waiting. “I love you to death” she later ironically confesses while simultaneously insisting that men and women are different. There is no escape for her. Goro is tired of running but refuses to be handcuffed, choosing perhaps the only path to freedom presented to him.

A nihilistic tale of gangster ennui in which life itself no longer has value, Velvet Hustler is a curiously cheerful affair despite its essential melancholy, Goro and Keiko sparring in a romantic war of attrition while he almost flirts with the dogged detective (Tatsuya Fuji) determined to bring him down. The kitschy production design gives way to Antonioni-esque shots of a strangely empty city while an ethereal sequence of dissolves eventually leaves the pair alone on the dance floor as if to imply their single moment of romance is but a brief dream of emotional escape. The trappings of post-war success are everywhere from Keiko’s elegant outfits to the cute red sports car and the weird club where Goro dad dances in front of his minions, not so much older than them but clearly out of place in this distinctly unhip seaside bar, but finally all there is is a dead end and an infinite emptiness the embrace of which is, perhaps, the only viable path to freedom.

If Nikkatsu Action movies had a ringtone it would probably just be “BANG!” but nevertheless you’ll have to wait more than three rings for the Kaboom! in the admittedly cartoonish slice of typically frivolous B-movie thrills that is 3 Seconds Before Explosion (爆破3秒前, Bakuha 3-byo Mae). Once again based on a novel by Japan’s master of the hard boiled Haruhiko Oyabu, 3 Seconds Before Explosion is among his sillier works though lesser known director Motomu Ida never takes as much delight in making mischief as his studio mate Seijun Suzuki. What he does do is make use of Diamond Guy Akira Kobayashi’s boyish earnestness to keep things running along nicely even if he’s out of the picture for much of the action.

If Nikkatsu Action movies had a ringtone it would probably just be “BANG!” but nevertheless you’ll have to wait more than three rings for the Kaboom! in the admittedly cartoonish slice of typically frivolous B-movie thrills that is 3 Seconds Before Explosion (爆破3秒前, Bakuha 3-byo Mae). Once again based on a novel by Japan’s master of the hard boiled Haruhiko Oyabu, 3 Seconds Before Explosion is among his sillier works though lesser known director Motomu Ida never takes as much delight in making mischief as his studio mate Seijun Suzuki. What he does do is make use of Diamond Guy Akira Kobayashi’s boyish earnestness to keep things running along nicely even if he’s out of the picture for much of the action. Before Seijun Suzuki pushed his luck too far with the genre classic

Before Seijun Suzuki pushed his luck too far with the genre classic

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.