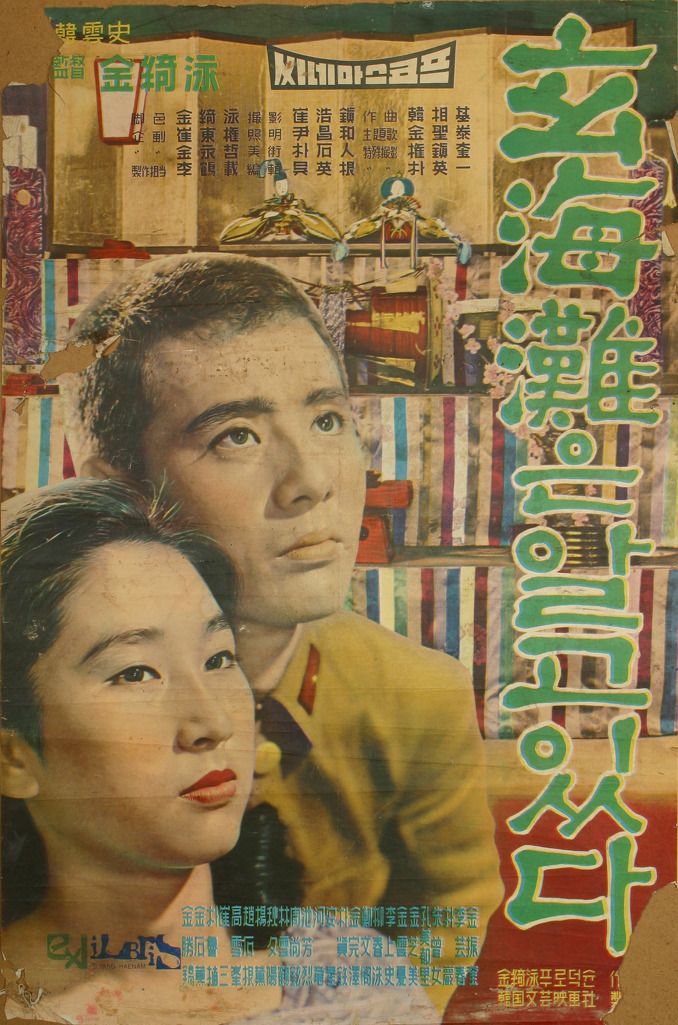

Released two years earlier, Kim Soo-Yong’s The Seashore Village had focused on the lives of women left behind while their husbands went to sea. Full Ship (滿船 / 만선, Manseon), meanwhile, more closely examines the lives of the men themselves along with the increasing pull towards modernity as this very traditional way of life becomes ever more precarious. Based on a play and another of Kim’s literary films, it nevertheless flies close to the wind in subtly challenging the effect that feudalistic capitalism has on each of these men’s lives as they find themselves dependent on the whims of the shipowner.

As Gom-chi (Kim Seung-ho) says, he’s fifty years old and he’s spent his life captaining someone else’s boat. Yet, he’s spent a lot of it toadying for the shipowner and justifying his reluctance to pay the fisherman by citing the shipowner’s expenses which include fuel for the boat, paying the union, and mending nets. The shipowner claims that he lives off debts and the fishermen actually owe him because he’s been lending them money and expects them to pay him back. Some of the other men suggest holding a gut ritual in his honour, but it’s unclear whether the shipowner is really as strapped as he says or merely hoarding all the money for himself. He dresses in fancy hanbok and looks more like a feudal lord than a contemporary business owner. When the fishermen do indeed come in with full boats and expect they’ll finally be getting what they’re owned, they receive only sacks of rotten hulled barely rather than rice. Still, most of them feel they have no choice than to suck up to the shipowner with even Gom-chi agreeing there are expenses to pay while drunkenly letting slip that he has savings and plans to buy his own boat only for the shipowner to find out and ban him from going to sea until he pays up what he owes.

Which is all to say, they’re between a rock and a hard place though “sea-crazy” Gom-chi holds tight to this way of life and has become estranged from his oldest surviving son Do-sam (Namkoong Won) who refuses to become a fisherman while Gom-chi’s wife, who has just given birth to a late baby though already in middle age, is opposed to letting their newborn grow up to go sea. They’ve already lost two sons to the waves, while Gom-chi’s father and grandfather were taken by the waters. To his mind, a fisherman dying at sea is merely going home and Do-sam is a failure and a coward for not following the tradition.

He blames this on the fact that Do-sam left the island to do his military service and has become corrupted after seeing a different way of life on land. Another man who escaped the island, Beom-soe (Park Noh-sik), has returned wearing a suit and looking like a successful businessman, though as we later discover he’s on the run for a crime committed in the city, symbolising what the end results of this urban corruption may be. Seul-seul (Nam Jeong-im), Gom-chi’s daughter, is also tempted by the city while travelling there to sell goods though almost run over by a bicyclist on her arrival demonstrating its many dangers. People stare and laugh at them, as if the island women with their old-fashioned hanbok had emerged from another world. They laugh at Seul-seul too when she gives in to temptation and gets her hair set and styled into a beehive paid for by her boyfriend Yeon-cheol (Shin Young-kyun) who has also resisted the sea in favour of starting an innovative pearl farming business which is starting to pay off, though Gom-chi still seems resistant to their marriage. Beom-soe is taken with Seul-seul’s island innocence and tries to convince her to come with him with fancy presents from the city of soaps, perfumes, and silk, but she continues to resist him as if sensing that his urban success is not to be trusted.

But, on the other hand, some seem to think it would be better to take their chances on land than continue with this harsh way of life. The film opens with a funeral in which a half-crazed old woman asks why they’re burying her son when he told her in a dream that he was alive just lost at sea. After a storm, Gom-chi comes back shouting of full boats, but they’re full of dead men drowned by the shipowner’s greed though he only complains about the damage to his vessel. Even the shamaness is a little bit corrupt, telling Do-sam’s mother that it would be inauspicious for him to marry because she’s having an affair with him herself, though prayers and rituals to the Dragon King are all they really have to protect them. Trapped between the sea and encroaching modernity that promises only more exploitation and misery, they have, as the poetic bookending narration suggests, only the life-giving, life-taking waters to turn to.