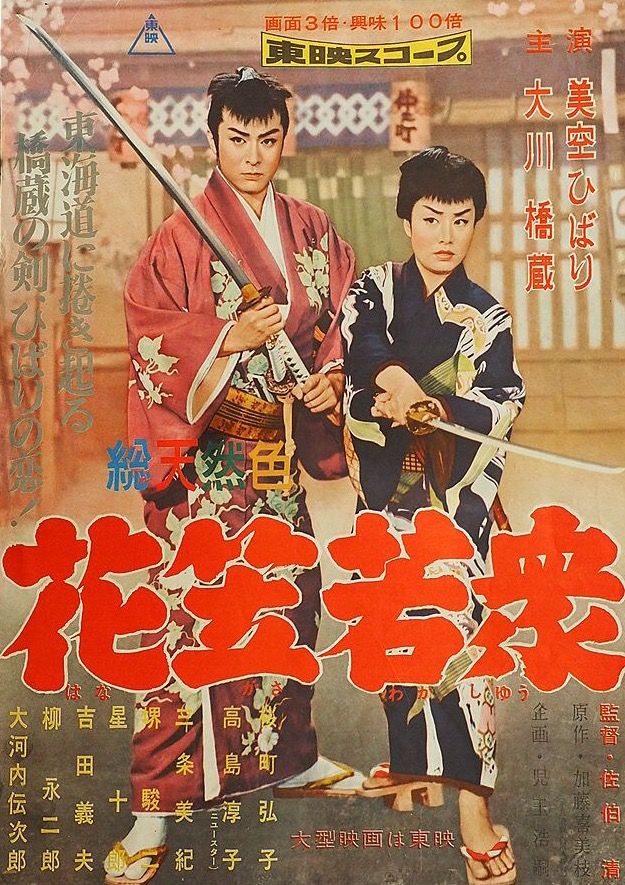

Hibari Misora takes on yet more Edo-era corruption in Kiyoshi Saeki’s musical adventure, The Young Boss (花笠若衆, Hanagasa Wakashu, AKA A Martial Crowd, Twin Princesses). A program picture director at Toei, Saeki mainly worked on jidaigeki and ninkyo eiga launching the Brutal Tales of Chivalry series, though he also became a frequent collaborator with Misora ironically enough mostly working on her contemporary films in which she often starred opposite Ken Takakura, representative actor in the noble gangster genre. Young Boss, however, is a jidaigeki musical adventure very much typical of those Misora was making at Toei at the time and once again finds her playing dual roles as a pair of twins separated at birth because of superstition and social stigma.

Opening and closing at a local Edo festival, the film introduces us to the second generation of Edoya Kichibei, Kichisaburo (Hibari Misora), as he steps in to protect a young woman who has accidentally annoyed a bunch of yakuza fulfilling his sidekick’s introduction that he “helps the weak and crushes the strong”. Kinpachi (Juro Hoshi) also describes him as a “man’s man”, though as we discover Kichisaburo is not a man at all but the niece/adopted daughter of a prominent merchant apparently raised as a boy. Kichisaburo, however, only learns this when a pair of samurai turn up to badger Kichibei about the whereabouts of his younger sister, Sano, who apparently served as a maid to the Ogiyama clan 18 years previously but was cast out with her younger daughter Yuki after giving birth to twin girls fathered by the lord. The other twin, Chiyo (also Hibari Misora), was raised in luxury in the palace and in the absence of a male heir and the lord’s failing health is in line to inherit the clan. As usual, however, courtly intrigue has led some to conclude that Yuki’s is the proper the claim. Kichibei attempts to convince them that Yuki passed away in infancy shortly after her mother and that he burnt her birth certificate, but the resemblance between the effete Kichisaburo and the lady Chiyo has not gone unnoticed both by the visiting samurai and the handsome Matanojo (Hashizo Okawa) who joins in with Kichisaburo’s battle against the yakuza and is in fact the betrothed husband of Chiyo.

Lady Chiyo appears only briefly but is the soul of courtly kindness, hugely regretting what has befallen her absent sister and affirming that should she return she would instantly surrender her claim to the clan in guilt that she has been raised in such luxury when Yuki was cast out to live with strangers. The dual roles in a sense reflect a perfect whole, Lady Chiyo’s feminine elegance contrasted with the rough Kichisaburo who has not been raised as a samurai but a merchant’s son like his sister set to inherit the family business. He is very attached to his adopted father, but also possesses a strong sense of justice often ignoring his pleas to stop getting into fights. Other than perhaps to disguise her true identity, there is no real explanation for why Kichisaburo has been raised as a boy though it seems that there would have been a time the ruse came to an end, Kichibei sadly lamenting that perhaps he has been jealously attempting to keep the child he loved so much with him against her better interests but explaining that he would have found her a nice husband in time, perhaps like that gallant samurai Matanojo.

Teaming up with him for purposes of revenge and justice, Kichisaburo begins to develop feelings for Matanojo though Kichibei reminds him that a townsperson would be “unfit to be a samurai’s wife”. Most of Misora’s films in which she stars as a feisty young woman see her undergoing a softening, drawing closer to conventional femininity often with marriage or at least a romance with a manly man on the horizon. The Young Boss meanwhile flirts with just this conclusion as Kichisaburo becomes Yuki while out on the road with Matanojo, dressing as an elegant princess and experiencing a vivid dream sequence in which she becomes his wife, but ultimately highlights the class rather than gender barriers between them in allowing to Yuki to return to her previous life as Kichisaburo while Chiyo remains a samurai noblewoman in a seemingly perfect mirroring which also represents a return to order.

Nevertheless, Misora finds numerous occasions for a cheerful song even in her manly guise finally even beating a taiko drum at the closing festival while joining in with several elaborately choreographed sword fights along the way with her customary gusto. A bittersweet ending, perhaps, but one in which Misora makes division of herself and unusually is allowed to remain feisty, defiant, and independent helping the weak and crushing the strong in an ever duplicitous Edo.

Musical number (no subtitles)