Hired to find a missing person no one really wants found, a detective begins to chase his own tail amid the impersonal vistas of the contemporary city in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Man Without a Map (燃えつきた地図, Moetsukita chizu). The fourth and final in his series of Kobo Abe adaptations and the only one in colour, the film’s Japanese title “burned-up map” may also, in its way, refer to the city of Tokyo which appears blurred out and indistinct in the sepia-tinted opening and is thereafter frequently shot from above as a depersonalised space where anonymous cars shuttle along highways like so many ants moving in rhythm with the momentum of the metropolis.

We follow a nameless detective (Shintaro Katsu) as he’s charged with investigating the disappearance of a 43-year-old salaryman, Hiroshi Nemuro, who turns out to have myriad other personalities and hasn’t been seen for six months. The man’s wife, Mrs Nemuro (Etsuko Ichihara), is not terribly helpful and the detective comes to wonder if the investigation itself is intended to further disguise the man’s whereabouts and prove that he really is a “missing person”. Yet this Tokyo is full of “missing people” including the detective who, we later learn, is a kind of fugitive himself. He apparently walked out on his wife (Tamao Nakamura), the owner of a successful boutique, because he couldn’t find his place there any more. He was once a salaryman too, and became a detective because it was the furthest thing he could think of from a regular job.

It confuses him that no one really seems to be interested in where Nemuro is or if he’s alright, only in the reason behind his disappearance. The more he chases him, the more he begins to take on Nemuro’s characteristics as if he were intended to slide into the space Nemuro has vacated. Toru Takemitsu’s eerie harpsichord score only seems to add to the hauntingly gothic quality of this quest. The question is whether such a thing as identity even exists any more. The detective puts on Nemuro’’s jacket, though it’s too small, and is mistaken for him, while a colleague of Nemuro’s insists that he’s seen him in the street and is sure it was Nemuro simply because of the unusual colour of his suit without ever seeing his face. Tashiro (Kiyoshi Atsumi) tells the detective that Nemuro had a secret hobby taking nude photos at a specialist club that caters to such things. The two of them are confident they’ve identified the woman in the picture based on her haircut, but the girl they speaks laughs and takes off her wig explaining that she was merely asked to wear it, so the woman in the photo could be anyone, including Nemuro’s own wife.

Nemuro apparently had a series of hobbies for which he’d obtained certificates because he said that having them helped him to feel anchored in his life, though he’s apparently unmoored now. Like the detective, he may have been trying on different personalities from car mechanic to school teacher looking for the right fit and a place he felt he belonged in rebellion against the depersonalisation of the salaryman society in which one man in a suit is as good as another. The detective finds an opposite number in the missing man’s brother-in-law (Osamu Okawa), a very modern, apparently gay gangster connected with a network of male sex workers sold on to influential elites, and a commune of similarly displaced people working as casual labourers that is overcome with corporate thugs and eventually trashed.

The trashing of the commune may have something to do with a man named Maeda who is a councillor in a town no one’s heard of, but was possibly involved in some shady business over which Nemuro may have been intending to blackmail him or blow a whistle with the assistance of his brother-in-law who helped him land a big contract at work. The more the detective investigates, the more confused he becomes. It’s impossible to follow the case as we might expect in a conventional noir thriller, but we’re not supposed to be looking at Nemuro’s disappearance so much as the detective’s gradually fracturing sense of self as he becomes lost in the anonymous city. He sees himself bury Mrs Nemuro in leaves only for her body somehow reduce itself to its component parts and sink into the street. Later her face is superimposed on the buildings as if she were looking down on him while he is lost and alone. Nemuro’s face also appears on buildings, though more as a metaphor as if the salaryman and the office building were one and the same and the reason the detective can’t find him is because he doesn’t really exist as a concrete identity. The detective spots a dead cat in the road and laments that he never thought to ask its name, but will try to think up a good one later. He might as well be talking about himself, now displaced, unmoored, and pursued among the city streets, a man without a map lost amid the simulacrum of an imaginary city.

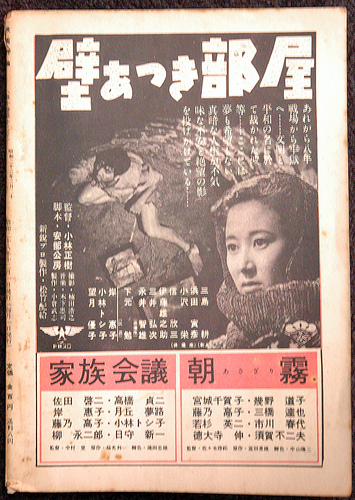

There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.

There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.