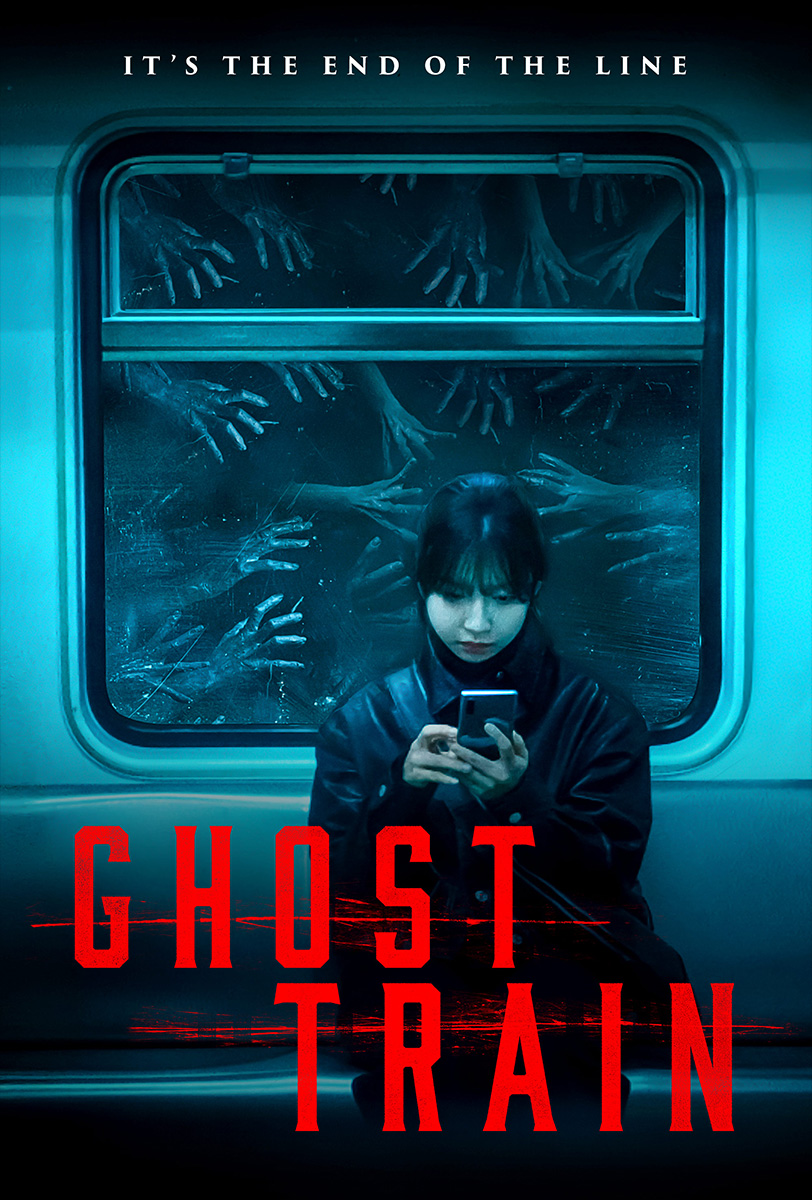

Why are there so many stories about haunted stations? Perhaps it’s their liminal status that gives them an eerie quality. By definition, you’re not supposed to stay here. To that extent, they’re a kind of purgatorial space between one destination or another. We leave so quickly it’s like a part of us is left behind, hovering, and never able to find the exit. In any case, Gwanglim seems to have its fair share of ghost stories as investigated by “horror queen” Da-kyung (Joo Hyun-young) in an attempt to boost the fortunes of her failing YouTube channel.

She herself admits that her problem is she’s run out of content, which is why she’s badgering the stationmaster (Jeon Bae-soo) for information on this supposedly haunted spot. The funny thing is that the stationmaster seems to know a lot more than you’d expect about these cases, including their full backstories, which have nothing to do with the station or his job. You’d think that would give Da-kyung pause for thought, but she’s already drunk on the promise of a scoop and has ironically convinced the stationmaster to talk with the gift of alcohol. As she continues to listen to his stories and the ratings of her channel improve, she takes on an increasingly vampiric appearance while the stationmaster seems to become ever sicker. Nevertheless, Da-kyung only becomes thirstier for gruesome tales even as the stationmaster tries to warn her off by asking what the real reason behind her animosity to rival beauty influencer Lina (Jung Han-bit) might be.

In this, her story parallels that of a young girl on the train who is insecure in her appearance and contemplating plastic surgery only to be haunted by a woman in bandages seemingly jealous of the beauty the young girl doesn’t know she already has. Da-kyung has a crush on her boss, Woo-jin (Choi Bo-min), but thinks he prefers Lina and not just because her channel pulls in millions of viewers. Lina is a classic mean girl who endlessly puts Da-kyung down as a means of asserting her own superiority while Da-kyung secretly looks down on her for her vacuity. As her channel improves and she grows in confidence, Da-kyung sheds her dowdy outfits for something a little more stylish but is still consumed by resentment towards Woo-jin in her, it seems possibly mistaken, belief that he prefers Lina because she aligns more closely with socially defined ideas of typical femininity in her tendency to behave like a silly girl who can’t do anything for herself except look pretty around men.

It is, as the stationmaster says, foolish to chase after what you think you’re missing and end up losing what you already had instead of learning to happy just with that. The other stories too are about overreaching greed, such as that of a homeless man who discovers a magic vending machine that disappears people and allows him to pick up their clothes and wallets to enrich himself though he never escapes the station despite his increasing desire to disappear random people until the point he realises he has consumed himself. Da-kyung is urged to delete her videos by someone who encountered something dangerous at the station, explaining that it’s built on the former site of a chapel that belonged to a cult where a mass suicide took place, further suggesting that the location itself is greedy for the souls of those who were, in a way, trying to turn away from this hyper-capitalistic vision of the world only to fall victim to it.

The stationmaster too dislikes those who profit from the misery or misfortune of others, which is what he assumes Da-kyung to be doing in her voracious appetite for ghost stories. In the very first tale, a young woman repeatedly bangs her head into a glass door, but no one attempts to help her. Everyone just moves to another carriage or generally away from her. These stories are only interesting for their gore and strangeness, no one really cares about the victims or learning from the past, which is to say we’re stuck in the station reliving the same trauma and unable to progress to a better a place. Da-kyung is stuck here most of all, and in her way, also hungry for souls lured in by lurid tales of untold horrors.

Ghost Train is released on Digital in the US on February 17 courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)