Following his ultramodern Buddhist Trilogy, Akio Jissoji casts himself back to the Kamakura era for a tale of desire and misuse in It Was a Faint Dream (あさき夢みし, Asaki Yumemishi, AKA Life of a Court Lady). Taking its name from a Heian era Buddist ode to transience, Faint Dream follows its melancholy heroine on a fleeting path of love, loss, romantic disappointment, and finally spiritual rebirth while the nation faces the external threat of putative invasion by warlike imperialists hellbent on domination and conquest.

Following his ultramodern Buddhist Trilogy, Akio Jissoji casts himself back to the Kamakura era for a tale of desire and misuse in It Was a Faint Dream (あさき夢みし, Asaki Yumemishi, AKA Life of a Court Lady). Taking its name from a Heian era Buddist ode to transience, Faint Dream follows its melancholy heroine on a fleeting path of love, loss, romantic disappointment, and finally spiritual rebirth while the nation faces the external threat of putative invasion by warlike imperialists hellbent on domination and conquest.

Shijo (Janet Hatta), an orphaned young woman taken as a concubine by the lord Tameie (Kotobuki Hananomoto), has returned home to await the birth of her child. The baby she is carrying, however, is not Tameie’s but that of another young noblemen, Saionji (Minori Terada), with whom Shijo had fallen in love before being taken by the lord. Hoping to pass the baby off as merely premature, Shijo has been deceiving Tameie and remains fearful she will be found out. Meanwhile, Saionji’s wife is also pregnant. When Saionji’s legitimate child is stillborn, an obvious solution presents itself and Shijo loses the first of her children.

A young woman without means or protectors, Shijo finds herself forced to indulge the whims of men in order to survive. Yet Tameie, falling ill, apparently thinks only of her when he pushes Shijo towards sleeping with other men in order to keep the peace, so that their resentment doesn’t become an all consuming evil. Thus it is that Tameie’s own brother, the high priest Ajari (Shin Kishida), falls for Shijo with a burning passion which Tameie fears could drag her down to hell with its implacable intensity. Reluctant and half disgusted, Shijo follows her lord’s advice, falling for the priest as she goes, and becoming pregnant with another child she must also lose.

Ajari’s radical Buddhist philosophy insists that chanting sutras is enough for salvation. It doesn’t matter if you’re high born or low or whether you believe or not, simply saying the words gets you into paradise. It’s a philosophy that appeals to Shijo for obvious reasons, but still she finds it near impossible to reconcile herself to her position of powerlessness within the court. A figure of desire, she is “courted” by just about every man she meets but has little right to refuse their attentions, especially as they often hold financial as well as social power over her. Tameie’s warning, ironic as it is in insisting that hell hath no fury like a man scorned, has its merit in bearing out the intensely destabilising properties of romantic love in a highly regimented society.

For all of that, however, Tameie is a romantic man, himself embittered by the disappointments of his life. Born to be a king, he prefers music and poetry to the sword but still laments his “betrayal” at the hands of the older generation who crowned him at three only to depose him at 16 and hand power to his 10-year-old brother with only a promise, apparently now broken, that his son would inherit the throne. Abandoned as a child, he has little sympathy for Shijo’s maternal pain on repeatedly having her children taken from her because of social propriety, merely reminding her that children and parents walk different paths and hers is evidently here, with him, at court.

Even so, men are content to have it both ways. Romance is a transient thing, Shijo is told, a flower which blooms in an instant of truth but then scatters. Attachment is the enemy of love, the wise man admires the flower as its falls but does not mourn its loss forever. Shijo finds this hard to understand, but continues to live her life as an object of desire rather than an active participant until she finally stops and makes a firm decision of her own in choosing to reject it. She becomes a nun and wanders the land looking for serenity despite being told that no woman can become a Buddha because of the five obstacles in her way no matter how nobly she might seek it.

Ironically enough, Shijo’s life is in itself a “faint dream”. She chooses to reject her desires, but admires other women for embracing theirs, and remains seemingly ageless while the fleeting loves of her youth grow old and fade. The lords sit around perfecting their poetry while boys are pulled off their farms to combat a Mongol invasion, and a deadly disease ravages the country. Shijo turns to ask her former lover about the child they conceived together, but it’s as if she were asking about someone else in another time. Having received her answer, she walks off into the distance, a nameless nun, free of the cares of the world and no longer burdened by desire.

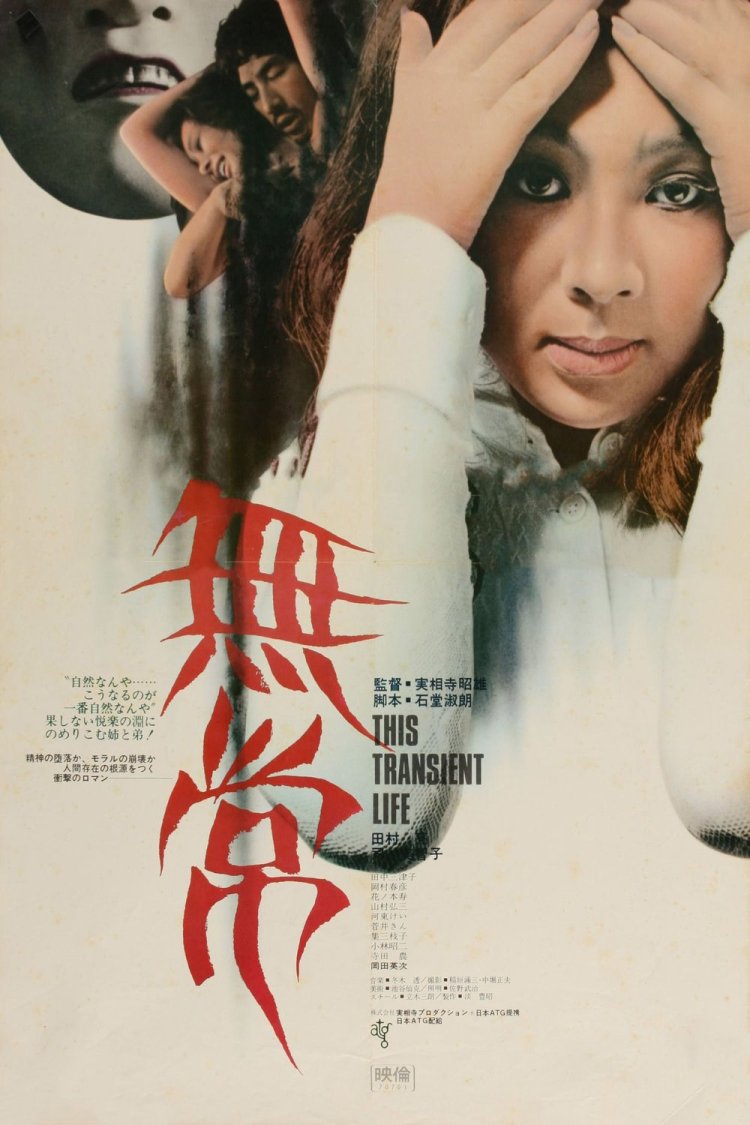

It Was a Faint Dream is the fourth of four films included in Arrow’s Akio Jissoji: The Buddhist Trilogy box set.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

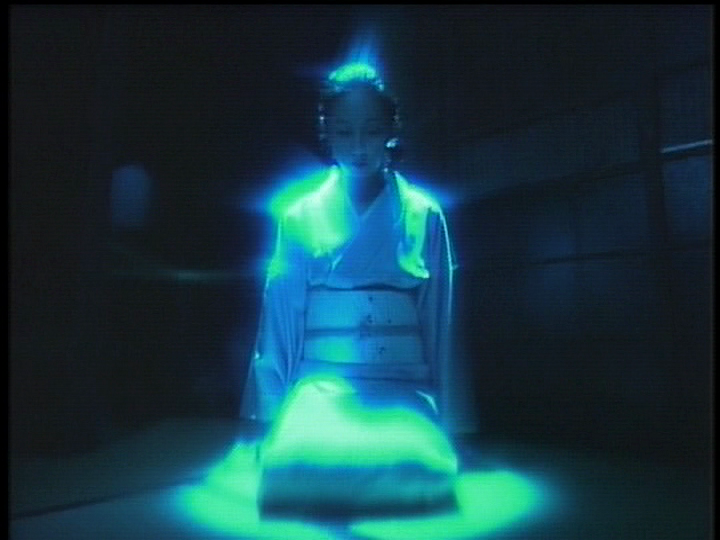

Akio Jissoji had a wide ranging career which encompassed everything from the Buddhist trilogy of avant-garde films he made for ATG to the Ultraman TV show. Post-ATG, he found himself increasingly working in television but aside from the children’s special effects heavy TV series, Jissoji also made time for a number of small screen movies including Blue Lake Woman (青い沼の女, Aoi Numa no Onna), an adaptation of a classic story from Japan’s master of the ghost story, Kyoka Izumi. Unsettling and filled with surrealist imagery, Blue Lake Woman makes few concessions to the small screen other than in its slightly lower production values.

Akio Jissoji had a wide ranging career which encompassed everything from the Buddhist trilogy of avant-garde films he made for ATG to the Ultraman TV show. Post-ATG, he found himself increasingly working in television but aside from the children’s special effects heavy TV series, Jissoji also made time for a number of small screen movies including Blue Lake Woman (青い沼の女, Aoi Numa no Onna), an adaptation of a classic story from Japan’s master of the ghost story, Kyoka Izumi. Unsettling and filled with surrealist imagery, Blue Lake Woman makes few concessions to the small screen other than in its slightly lower production values.