The London Korean Film Festival has always made a space for documentary in its packed out programme but for this year’s edition they’ve decided to go a little further and give it a spotlight of its own with two weekends dedicated to the art. On August 11/12, and 18/19, six short and feature lengths films will be screened with directors Kim Dong-won and Song Yun-hyeok making an appearance to present their work.

11th August – Birkbeck Cinema

11.30am: A Slice Room

Song Yun-hyeok examines the social reality behind the prosperous facade of contemporary Korean society through the lives of those living in “slice rooms”. Director Song Yun-hyeok will also be in conversation with Nam In Young following the screening.

2.30pm: The Sanggyedong Olympics / The 6 Day Struggle at the Myeongdong

Kim Dong-won’s 1988 documentary Sanggyedong Olympics follows the resistance movement towards urban regeneration amongst a community north of Seoul who had been unfairly evicted from their homes without proper compensation or adequate time to find new accommodation. Kim planned to stay only one day but ended up living amongst the community for three years.

The 6 Day Struggle at the Myeongdong Cathedral, completed during 1996-7, looks back at the pivotal 1987 sit-in which became a catalyst for the June democracy movement.

Following the two short docs, Kim Dong-won will also be in conversation with Nam In Young.

12th August – Birkbeck Cinema

1.30pm: Repatriation

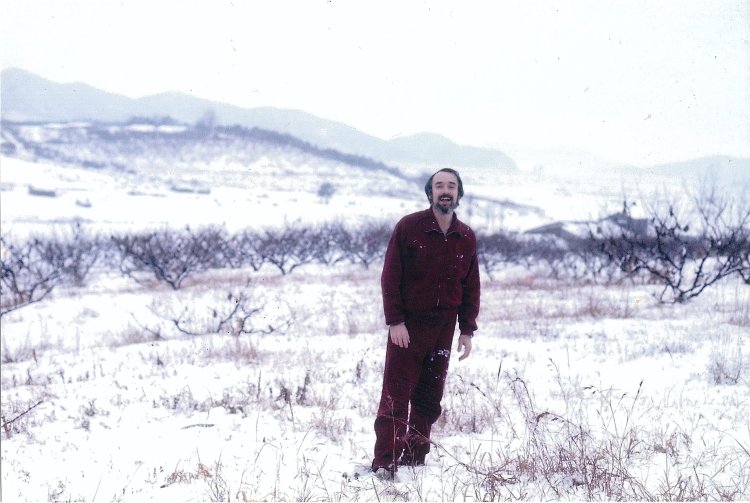

In what many consider his masterpiece, Kim Dong-won examines the lives of the “unconverted” – North Korean “spies” who refuse to renounce their communist beliefs despite longterm imprisonment in the South. Refused the possibility of returning to the North on release, most were left without support in South Korea facing economic hardship and social stigma, dependent on solidarity networks to help them integrate into society. Kim follows two such men over a decade as they try to rebuild their lives in the fluctuating political climate of the ’90s.

The film will be followed by a conversation with Kim Dong-won chaired by Chris Berry.

4.45pm: Roundtable

A roundtable panel discussion chaired by Professor Chris Berry discussing the Korean independent documentary scene from the late ’80s to the present. Nam In Young of Dongseo University will provide an overview of filmmaking collectives within the sociopolitical history of South Korea while directors Kim Dong-won and Song Yun-hyeok will be on hand to offer their personal experiences.

18th August – Korean Cultural Centre

3pm: Soseongri

Park Bae-il’s Soseongri follows a community of elderly farmers facing rural depopulation problems who find themselves in conflict with the police when the decision is taken to place the THAAD anti-aircraft system in their village.

Park Bae-il’s Soseongri follows a community of elderly farmers facing rural depopulation problems who find themselves in conflict with the police when the decision is taken to place the THAAD anti-aircraft system in their village.

19th August – Korean Cultural Centre

3pm: Jung Il-woo, My Friend

Kim Dong-won’s most recent film pays tribute to North American Jesuit priest, Jung Il-woo, who dedicated his life to improving the lives of the poor in South Korea.

All the events are free to attend but tickets must be booked in advance via the links above. Full details for all the films are available via the official website, and you can keep up with all the latest news via the festival’s Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, Instagram and YouTube channels

Following on from the

Following on from the  Lee Byung-hun stars as a conflicted high school teacher who begins to see echoes of a woman he loved and lost years ago in a male student.

Lee Byung-hun stars as a conflicted high school teacher who begins to see echoes of a woman he loved and lost years ago in a male student. Kim Ki-young recasts the folly of war as a romantic melodrama in which a Korean conscript to the Japanese army receives harsh treatment from his sadistic superior but later falls in love with a Japanese woman.

Kim Ki-young recasts the folly of war as a romantic melodrama in which a Korean conscript to the Japanese army receives harsh treatment from his sadistic superior but later falls in love with a Japanese woman. Moon Jeong-suk stars as a determined young woman hellbent on becoming a judge in defiance of social convention which views marriage and motherhood as the only paths to female success. Encouraged by her father but forced to dodge her mother’s constant attempts to marry her off, she pursues her dream in spite of intense disapproval.

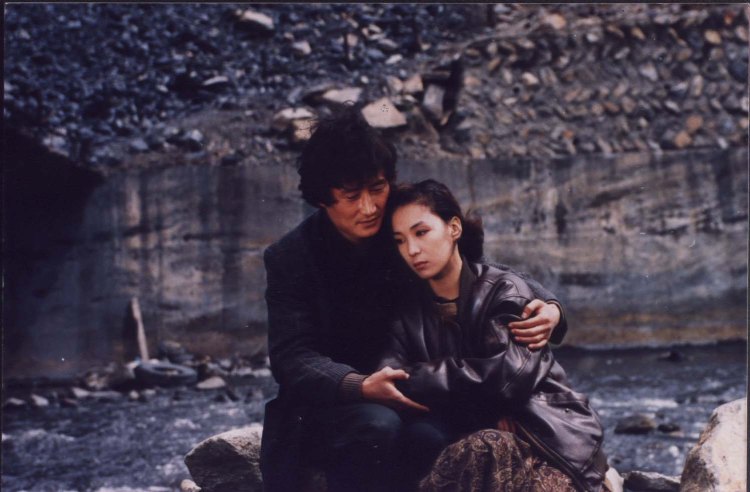

Moon Jeong-suk stars as a determined young woman hellbent on becoming a judge in defiance of social convention which views marriage and motherhood as the only paths to female success. Encouraged by her father but forced to dodge her mother’s constant attempts to marry her off, she pursues her dream in spite of intense disapproval. Kim Ki-duk (the old one!) draws inspiration from Ko Nakahira’s Dorodarake no Junjo for a tragic tale of love across the class divide as poor boy Du-su (Shin Seong-il) and Ambassador’s daughter Johanna (Um Aeng-ran) meet by chance and fall in love. Faced with the impossibility of their “pure” love in an “impure world” the pair find themselves an impasse, unable to reconcile their true feelings with the demands of the society in which they live.

Kim Ki-duk (the old one!) draws inspiration from Ko Nakahira’s Dorodarake no Junjo for a tragic tale of love across the class divide as poor boy Du-su (Shin Seong-il) and Ambassador’s daughter Johanna (Um Aeng-ran) meet by chance and fall in love. Faced with the impossibility of their “pure” love in an “impure world” the pair find themselves an impasse, unable to reconcile their true feelings with the demands of the society in which they live.  Im Kwon-taek’s “artistic breakthrough” stars Ahn Sung-ki as a young man who has abandoned his girlfriend and university studies to become a Buddhist monk but later meets an older man who indulges all of life’s Earthly pleasures such as wine and women.

Im Kwon-taek’s “artistic breakthrough” stars Ahn Sung-ki as a young man who has abandoned his girlfriend and university studies to become a Buddhist monk but later meets an older man who indulges all of life’s Earthly pleasures such as wine and women. Park Kwang-su revisits the democratisation movement in its immediate aftermath as a student who hides from the authorities in a small mining village finds himself at odds with his environment while haunted by the possibility that his longed for revolution will not come to pass.

Park Kwang-su revisits the democratisation movement in its immediate aftermath as a student who hides from the authorities in a small mining village finds himself at odds with his environment while haunted by the possibility that his longed for revolution will not come to pass.

After a brief pause, the

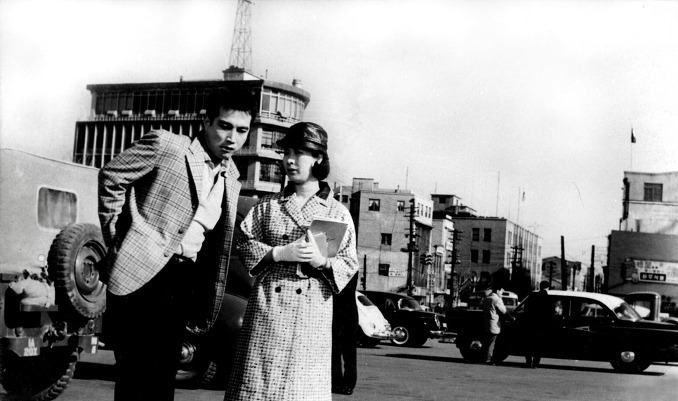

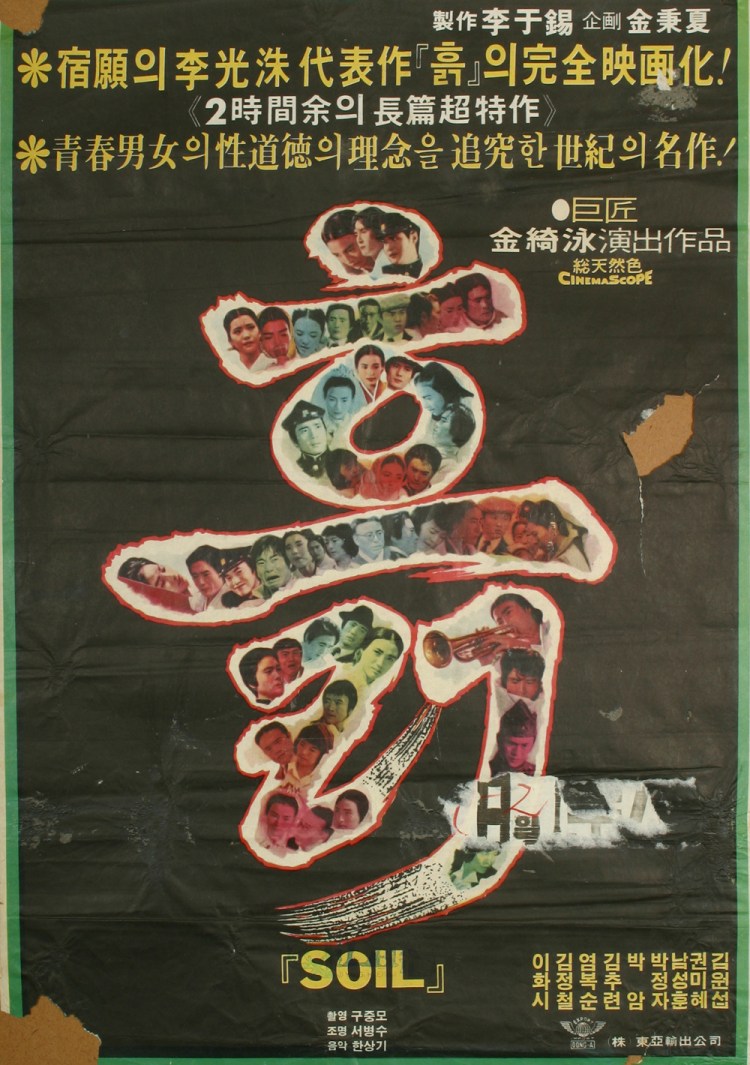

After a brief pause, the  Housemaid director Kim Ki-young adapts Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel of resistance in which a poor boy studies law in Seoul and marries the daughter of the landowner he once served only to decide to return and help his home village suffering under Japanese oppression.

Housemaid director Kim Ki-young adapts Yi Kwang-su’s 1932 novel of resistance in which a poor boy studies law in Seoul and marries the daughter of the landowner he once served only to decide to return and help his home village suffering under Japanese oppression.

Directed by Chung Ji-young, White Badge adapts Anh Junghyo’s autobiographical Vietnam novel in which a traumatised writer (played by Ahn Sung-ki) is forced to address his wartime past when an old comrade comes back into his life.

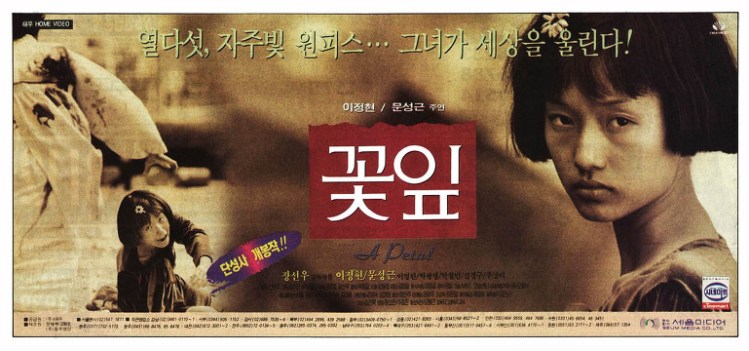

Directed by Chung Ji-young, White Badge adapts Anh Junghyo’s autobiographical Vietnam novel in which a traumatised writer (played by Ahn Sung-ki) is forced to address his wartime past when an old comrade comes back into his life. Adapting the novel by Choe Yun, Jang Sun-woo examines the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre through the story of a little girl who refuses to leave the side of a vulgar and violent man no matter how poorly he treats her.

Adapting the novel by Choe Yun, Jang Sun-woo examines the legacy of the Gwangju Massacre through the story of a little girl who refuses to leave the side of a vulgar and violent man no matter how poorly he treats her. Adapted from a novel by writer and activist Hwang Sok-young, Im Sang-soo’s The Old Garden follows an activist released from prison after 17 years who cannot forget the memory of a woman who helped him when he was a fugitive in the mountains.

Adapted from a novel by writer and activist Hwang Sok-young, Im Sang-soo’s The Old Garden follows an activist released from prison after 17 years who cannot forget the memory of a woman who helped him when he was a fugitive in the mountains. The debut feature from Kim Sung-je, the Unfair is an adaptation of Son Aram’s courtroom thriller which draws inspiration from the Yongsan Tragedy in which residents protesting redevelopment were forcibly evicted and several lives were lost including one of a police officer.

The debut feature from Kim Sung-je, the Unfair is an adaptation of Son Aram’s courtroom thriller which draws inspiration from the Yongsan Tragedy in which residents protesting redevelopment were forcibly evicted and several lives were lost including one of a police officer. An adaptation of the novel by Kim Ae-ran who will also be present for a Q&A, E J-yong’s My Brilliant Life stars Gang Dong-won and Song Hye-kyo as teenage parents raising a son who turns out to have a rare genetic condition which causes rapid ageing.

An adaptation of the novel by Kim Ae-ran who will also be present for a Q&A, E J-yong’s My Brilliant Life stars Gang Dong-won and Song Hye-kyo as teenage parents raising a son who turns out to have a rare genetic condition which causes rapid ageing.

Following a long series of teaser screenings which culminated with Cannes hit

Following a long series of teaser screenings which culminated with Cannes hit  The

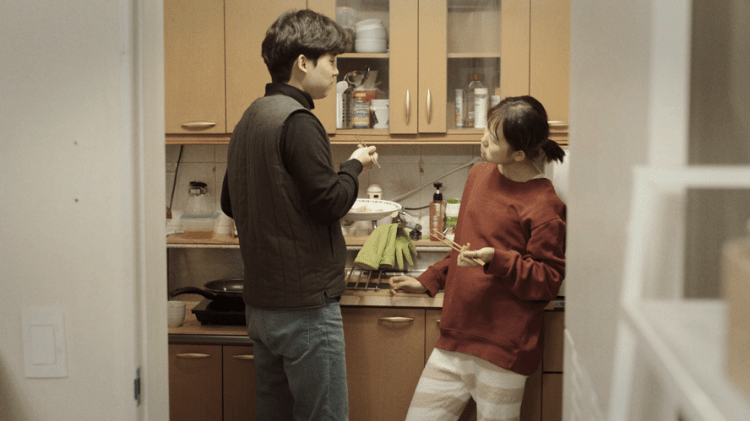

The  Closing the festival will be the second film from Kim Dae-hwan who picked up the best new director award at Locarno for this awkward tale of familial disconnection.

Closing the festival will be the second film from Kim Dae-hwan who picked up the best new director award at Locarno for this awkward tale of familial disconnection.  The special focus for this year’s festival is Korean Noir and Korean cinema has certainly had a long and proud history of gritty, existential crime thrillers. Running right through from the ’60s to recent Cannes hit The Merciless, the Korean Noir strand aims to illuminate the dark side of society through its compromised heroes and conflicted villains.

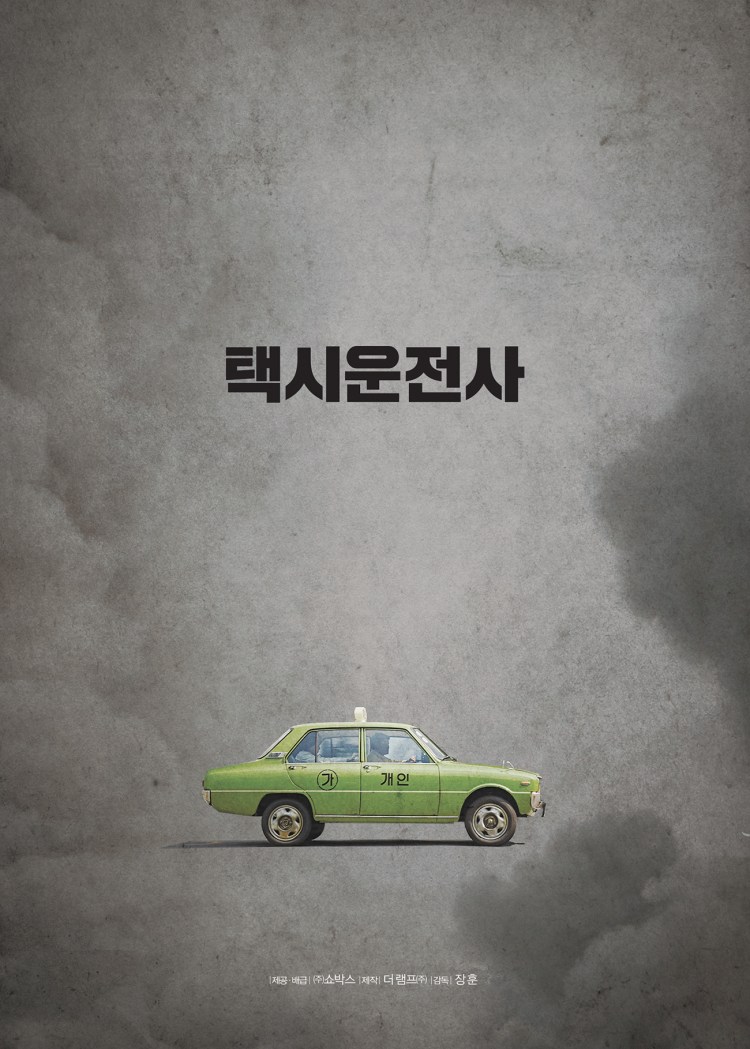

The special focus for this year’s festival is Korean Noir and Korean cinema has certainly had a long and proud history of gritty, existential crime thrillers. Running right through from the ’60s to recent Cannes hit The Merciless, the Korean Noir strand aims to illuminate the dark side of society through its compromised heroes and conflicted villains. The best in recent cinema across the previous year ranging from period drama to financial thriller, gangland action, social drama, and horror.

The best in recent cinema across the previous year ranging from period drama to financial thriller, gangland action, social drama, and horror. Programmed by Tony Rayns, this year’s indie strand has a special focus on documentary filmmaker Jung Yoon-suk who will be attending the festival in person to present his films.

Programmed by Tony Rayns, this year’s indie strand has a special focus on documentary filmmaker Jung Yoon-suk who will be attending the festival in person to present his films. Focussing on female viewpoints this year’s Women’s Voices strand includes one narrative feature and four short films.

Focussing on female viewpoints this year’s Women’s Voices strand includes one narrative feature and four short films. Three films from legendary director Bae Chang-ho each starring Ahn Sung-ki.

Three films from legendary director Bae Chang-ho each starring Ahn Sung-ki. Workers’ rights and examinations of the Yongsan tragedy in which five civilians and one police officer lost their lives during a protest against redevelopment dominate the feature documentary strand.

Workers’ rights and examinations of the Yongsan tragedy in which five civilians and one police officer lost their lives during a protest against redevelopment dominate the feature documentary strand. Two charming yet very different animated adventures aimed at a younger/family audience.

Two charming yet very different animated adventures aimed at a younger/family audience. A selection of shorts from the

A selection of shorts from the

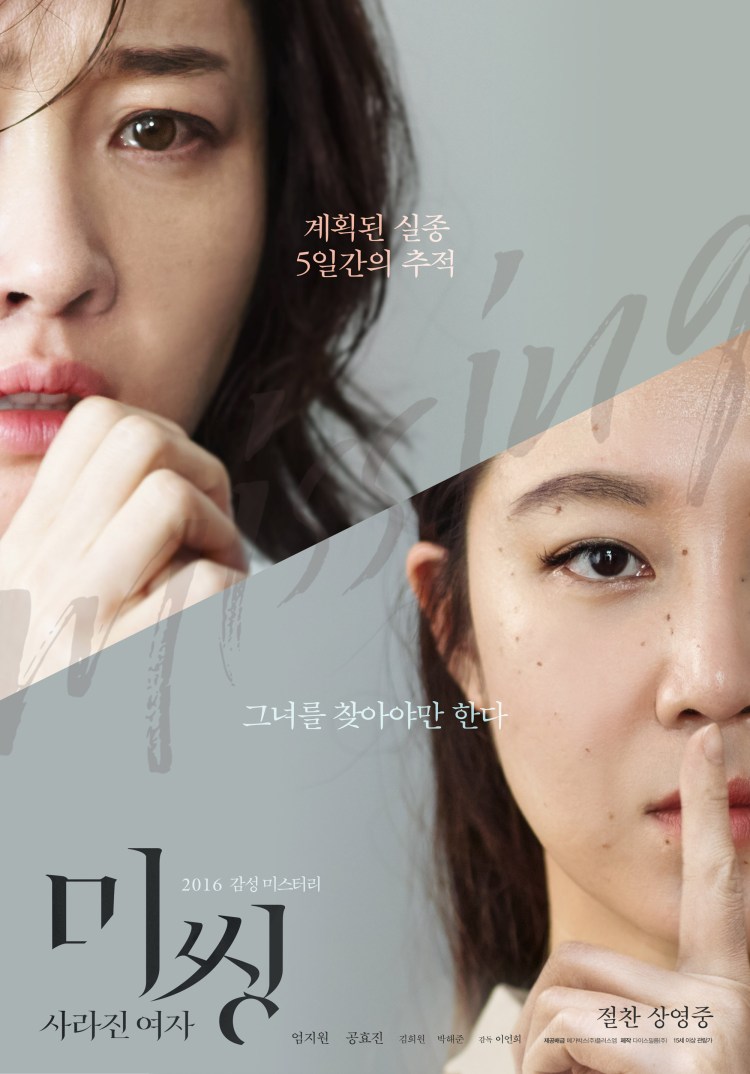

Since ancient times drama has had a preoccupation with motherhood and a need to point fingers at those who aren’t measuring up to social expectation. E Oni’s Missing plays out like a Caucasian Chalk Circle for our times as a privileged woman finds herself in difficult circumstances only to have her precious daughter swept away from her just as it looked as if she would be lost through a series of social disadvantages. Missing is partly a story of motherhood, but also of women and the various ways they find themselves consistently misused, disbelieved, and betrayed. The two women at the centre of the storm, desperate mother Ji-sun (Uhm Ji-won) and her mysterious Chinese nanny Han-mae (Gong Hyo-jin) are both in their own ways tragic figures caught in one frantic moment as a choice is made on each of their behalves which will have terrible, unforeseen and irreversible consequences.

Since ancient times drama has had a preoccupation with motherhood and a need to point fingers at those who aren’t measuring up to social expectation. E Oni’s Missing plays out like a Caucasian Chalk Circle for our times as a privileged woman finds herself in difficult circumstances only to have her precious daughter swept away from her just as it looked as if she would be lost through a series of social disadvantages. Missing is partly a story of motherhood, but also of women and the various ways they find themselves consistently misused, disbelieved, and betrayed. The two women at the centre of the storm, desperate mother Ji-sun (Uhm Ji-won) and her mysterious Chinese nanny Han-mae (Gong Hyo-jin) are both in their own ways tragic figures caught in one frantic moment as a choice is made on each of their behalves which will have terrible, unforeseen and irreversible consequences. The era of hero priests might be well and truly behind us but at least when it comes to the exorcism movie, the warrior monk resurfaces as the valiant men of God face off against pure evil itself risking both body and soul in an attempt to free the unfortunate victim of a possession from their torment. To many, the very idea sounds as if it belongs in the medieval era – what need have we for demons now that we posses such certain, scientific knowledge? There are, however, things far more ancient than man which are far more terrifying than our ordinary villainy.

The era of hero priests might be well and truly behind us but at least when it comes to the exorcism movie, the warrior monk resurfaces as the valiant men of God face off against pure evil itself risking both body and soul in an attempt to free the unfortunate victim of a possession from their torment. To many, the very idea sounds as if it belongs in the medieval era – what need have we for demons now that we posses such certain, scientific knowledge? There are, however, things far more ancient than man which are far more terrifying than our ordinary villainy.