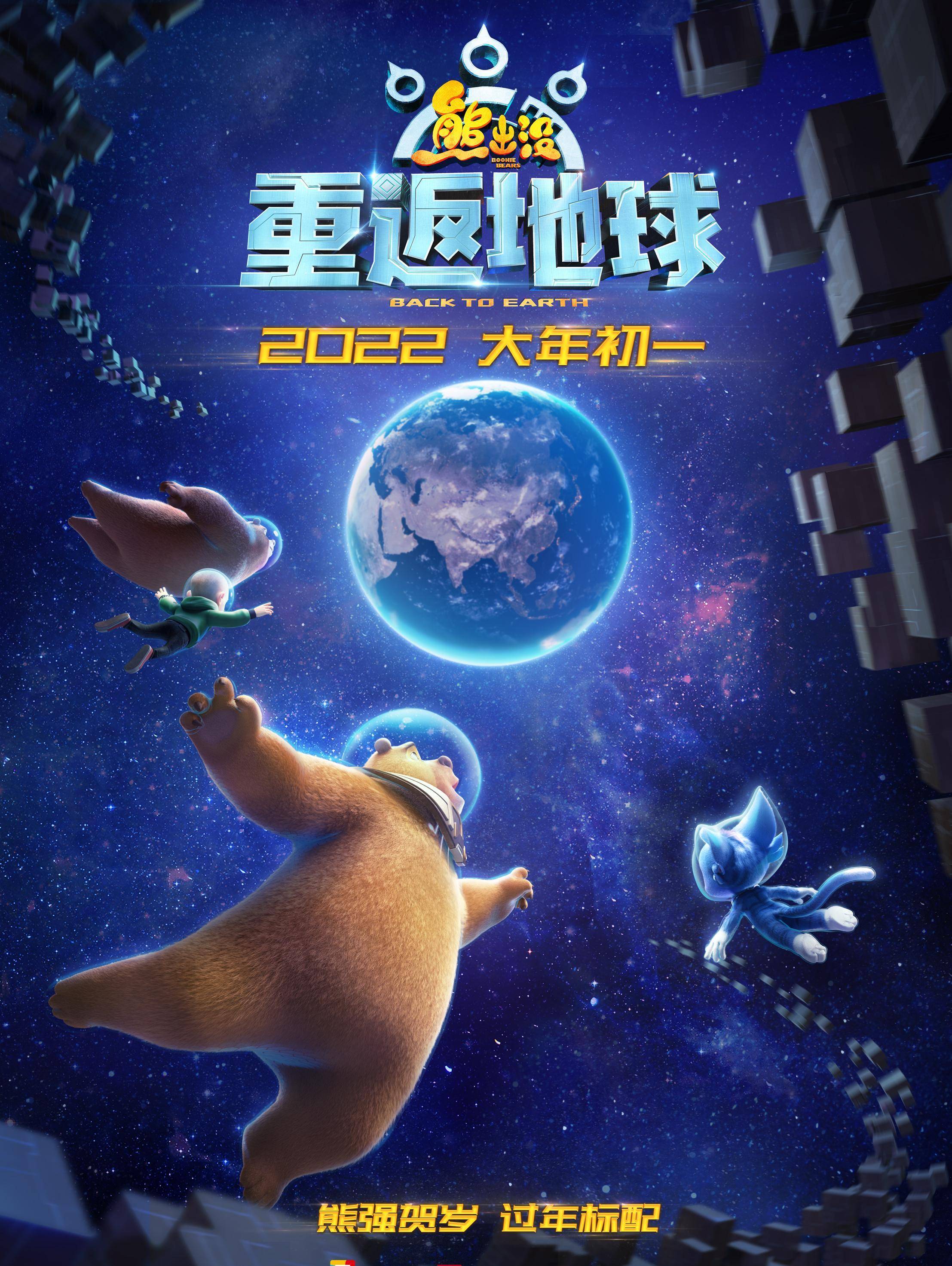

One of the biggest animation franchises in Mainland China, Boonie Bears began airing as a children’s cartoon show back in 2012 and has produced over 600 episodes across 10 seasons. The latest movie, Boonie Bears: Back to Earth (熊出没·重返地球, xióng chūmò: chóngfǎn dìqiú), is the franchise’s eighth theatrical movie and again proved popular at the box office on its Lunar New Year release. As might be expected for a series revolving around woodland creatures, the first antagonist was a logger who later came round and teamed up with the animals to protect the forest, the franchise has a strong if potentially subversive ecological theme which reverberates throughout Back to Earth.

In fact, the chief job of unreliable younger brother bear Bramble (Zhang Bingjun) is sorting rubbish into the appropriate bins to keep the forest tidy. Daydreaming he casts himself as superhero battling a giant trash monster symbolising the destructive effects of the buy now pay later philosophy of the modern consumerist society. In any case Bramble’s cheerful days of chasing ice cream and just generally enjoying life in the forest are disrupted when he’s almost wiped out by bits of a falling spaceship and becomes the repository for all of its knowledge. This brings him to the attention of alien space cat Avi who needs his brain to locate his ship but is also being chased by a gang of nefarious criminals led by an amoral entrepreneur who wouldn’t let a little thing like the survival of the Earth interfere with her desires for untold wealth and power.

As it turns out Avi also has a few lessons to offer as to the costs of irresponsible industrialisation having been born in an ultra-advanced cat society buried deep in the Earth’s core. The over mining of a valuable mineral soon destroyed the environment forcing the cats to flee into space looking for a new home. Avi hopes to return to his home city which lies abandoned as a kind of cat Atlantis accessible only with a valuable necklace which he needs Bramble’s help to retrieve. To begin with, the relationship between the pair is less than harmonious, though they soon bond in their shared quest to stop the evil corporate entities taking over the ancient technology and causing the death of the forest through their insatiable greed.

Then again as one of the other creatures had put it, “you can’t rely on Bramble”, cross that he never pulls his weight and is always off in a daydream or chasing the next tasty treat. While Avi poses as an adorable kitten trying to convince Bramble to use his brain to help get the spaceship back, the others become even more disappointed in him believing that he’s taken against the cat out of jealously and resentment. Yet the lesson that everyone finally has to learn is that it doesn’t matter if Bramble isn’t the smartest or most hard working because he is strong and kind and has plenty to offer of his own. His gentle bear hug eventually saves the world in healing the villainess’ emotional pain so she no longer has any need to fill the void with cruel and ceaseless acquisition.

Aside from the gentle messages of the importance of protecting the forest from the ravages of untapped capitalism, after all “this is our only homeland”, the film packs in a series of family-friendly gags including a surprising set piece in which Bramble dresses up as Marilyn Monroe to recreate the famous subway vent moment from The Seven Year Itch, while a pair of eccentric scrap merchants with a taste for rhyme provide additional comic relief. Even in the villains get a lengthy cabaret floorshow to mis-sell their evil mission to the guys from the forest belatedly coming to Bramble’s rescue. In any case, thanks to everyone’s support and encouragement Bramble finally gets to become the hero he always wanted to be proving that he’s not unreliable and even if he doesn’t always succeed is doing his best. Boasting high quality animation, genuinely funny gags, some incredibly catchy tunes and well choreographed musical sequences along with a warmhearted sense of sincerity, Boonie Bears: Back to Earth is another charming adventure for the much loved woodland gang.

Boonie Bears: Back to Earth is in UK cinemas from 27th May courtesy of The Media Pioneers (screening in a family-friendly English dub).

Original trailer (no subtitles)