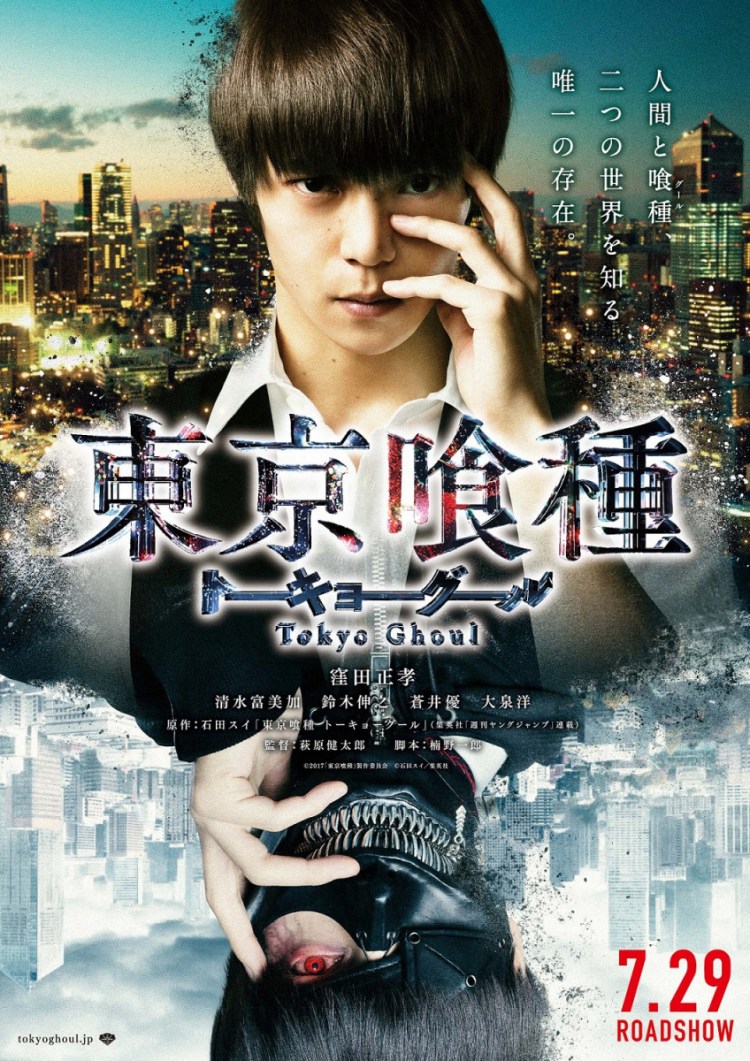

In Tokyo Ghoul, regular university student Ken Kaneki (Masataka Kubota) had to learn to accept the parts of himself he didn’t like in order to become the kind of man he wanted to be. Of course, the situation was more complicated than that faced by most young men because Ken Kaneki’s darkness was born of being seduced by a beautiful woman who turned out to be a “ghoul” – a supernatural being craving human flesh, something he later became himself when they were both injured in a freak accident after which he got some of her organs. The sequel, Tokyo Ghoul S (東京喰種 トーキョーグール【S】) finds him in a more centred place, having accepted his new nature as neither human nor ghoul but a bridge between the two. Now he has a series of different questions to face in trying help others accept themselves in the same way as they too wonder if there are some parts of themselves so dark that if they revealed them they could never be loved.

In Tokyo Ghoul, regular university student Ken Kaneki (Masataka Kubota) had to learn to accept the parts of himself he didn’t like in order to become the kind of man he wanted to be. Of course, the situation was more complicated than that faced by most young men because Ken Kaneki’s darkness was born of being seduced by a beautiful woman who turned out to be a “ghoul” – a supernatural being craving human flesh, something he later became himself when they were both injured in a freak accident after which he got some of her organs. The sequel, Tokyo Ghoul S (東京喰種 トーキョーグール【S】) finds him in a more centred place, having accepted his new nature as neither human nor ghoul but a bridge between the two. Now he has a series of different questions to face in trying help others accept themselves in the same way as they too wonder if there are some parts of themselves so dark that if they revealed them they could never be loved.

While Ken goes about his regular student life working part-time at ethical ghoul cafe Anteiku, a ghoul serial killer known as “The Gourmet” (Shota Matsuda) has been making the news after targeting a high profile model (Maggy) whom he stalked and killed simply to taste her heterochromatic eyes. Tsukiyama, as we later learn his name to be, is a dandyish fopp living in a Western-style country house complete with servants who serve him only the finest meals well presented to hide their dark genesis. On catching a whiff of Ken’s unique human/ghoul scent, he knows he must taste him and puts a nefarious plan in motion in order to lure him to a mysterious ghoul-only restaurant where humans are butchered live for show while the clientele salivate over scenes of intense cruelty.

That’s all too much for poor Ken. He can’t understand how anybody could act with so little regard for life. The cafe owner pointedly asks him if he feels pity when looking at the butchered flesh of an animal, which he of course does not. The ghouls feel much the same, humans are their prey – they can’t help what they are, but living under the intense fear of discovery in an obviously hostile world has made them cruel and resentful to the extent that they no longer understand the value of life. The ghouls that Ken knows, the ones which frequent Anteiku, are different. They have resolved to live ethically and respect lives both human and ghoul equally.

Ken’s friend and colleague Touka (Maika Yamamoto), however, is beginning to have her doubts. In the first film we saw her pursue a touching friendship with classmate Yoriko (Nana Mori) whose cooking she made a point of eating solely as a means of connection despite the fact that human food makes her ill. Now she fears she’s doing the wrong thing, that it will only hurt more if her friend finds out her secret and rejects her, or worse that she may put her in danger. Therefore, she counsels Ken to distance himself from his overly cheerful friend Hide (Kai Ogasawara) and the human world in general, threatening that she herself will kill Hide if he discovers that Ken is a ghoul. As expected, Ken ignores her advice but is mildly shaken by it. Deciding to intervene when his sometime enemy Nishiki (Shunya Shiraishi) is being beaten up in the street, he discovers a better future on learning that Nishiki is living with a human woman who knows he is a ghoul, but loves him anyway.

Though Kimi’s (Mai Kiryu) justifications that she can live with the fact her boyfriend kills people and eats them so long as he leaves her friends and family alone is a little worrying, it is a touching example of the film’s positive message that there is no secret so terrible that it means someone can’t be loved. Kimi accepts Nishiki’s nature as a ghoul, aware of the fact he can’t help what he is and that if she had been born a ghoul she would be the same. Touka fears rejection, but on catching sight of her bright red wings Kimi utters the single word “beautiful”, seeing only goodness without fear or hate.

Tsukiyama meanwhile seems to have gone in the opposite direction, pursuing his desires to the point of obsession in a quest for ever greater sensation. He stalks and murders the model to devour her eyes in an especial piece of irony, while his pursuit of Ken takes on an intensely homoerotic quality. Using the same tactics as Tokyo Ghoul‘s Rize, Tsukiyama picks Ken up through bonding over books, invites him to “dinner” and later sends him an invitation accompanied by a single red rose. Despite the romanticism, however, he soon reverts to type in blaming Ken for his actions. “You’re making me this way”, he insists, “take responsibility”, like every abuser ever simultaneously accepting that his behaviour is inappropriate and justifying it as a consequence of someone else’s actions. In the end, Tsukiyama’s illicit desires consume him, while Ken’s act of self-sacrifice once again allows him to be the human/ghoul bridge combatting Tsukiyama’s rapacious cruelty with an open-hearted generosity which pushes Touka to the fore so that she too can learn that peaceful co-existence is possible when there is trust and understanding on both sides.

Nishiki tells Ken his problem is that he’s too nice, but that’s not a bad thing to be because he just might “save somebody someday”. Niceness as a superpower might be an odd message for a movie about flesh eating monsters almost indistinguishable from regular humans, but perhaps that’s what will save us in the end, a generosity of spirit that makes it possible for us each to accept each other’s darkness in acknowledgement of our own. Less stylistically interesting than the first instalment, Tokyo Ghoul S may be a kind of bridge movie in a possible trilogy (a sequel is teased in a brief mid-credits sequence featuring a mysterious character who makes several unexplained appearances throughout the film), but nevertheless does its best to further the Tokyo Ghoul mythology as its hero finds his strength in difference and mutual understanding.

Tokyo Ghoul S screens in the US for three nights only on Sept. 16/18/20 courtesy of Funimation. Check the official website to find out where it’s playing near you!

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Despite the potential raciness of the title, The Liar and his Lover (カノジョは嘘を愛しすぎてる, Kanojo wa Uso wo Aishisugiteru) is another innocent tale of youthful romance adapted from a shojo manga by Kotomi Aoki. As is customary in the genre, the heroine is cute yet earnest, emotionally honest and fiercely clear cut whereas the hero is a broken hearted artist much in the need of the love of a good woman. Innocent and chaste as it all is, Liar also imports the worst aspects of shojo in its unseemly age gap romance between a 25 year old musician and the 16 year old high school girl he picks up on a whim and then apparently falls for precisely because of her uncomplicated goodness.

Despite the potential raciness of the title, The Liar and his Lover (カノジョは嘘を愛しすぎてる, Kanojo wa Uso wo Aishisugiteru) is another innocent tale of youthful romance adapted from a shojo manga by Kotomi Aoki. As is customary in the genre, the heroine is cute yet earnest, emotionally honest and fiercely clear cut whereas the hero is a broken hearted artist much in the need of the love of a good woman. Innocent and chaste as it all is, Liar also imports the worst aspects of shojo in its unseemly age gap romance between a 25 year old musician and the 16 year old high school girl he picks up on a whim and then apparently falls for precisely because of her uncomplicated goodness. In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not.

In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not. The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with.

The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with. Jellyfish Eyes (めめめのくらげ, Mememe no Kurage) is the feature film debut of the internationally popular Japanese artist, Takashi Murakami. Well known for his cutesy character designs which are as likely to turn up in the world’s best regarded art galleries as they are on a kid’s backpack, Murakami is one of Japan’s most highly regarded art exports. Having unsuccessfully tried to raise interest in the more obvious totally CG animation, Murakami has enlisted the help of gore master Yoshihiro Nishimura for some director’s chair tips in creating a live action/CGI hybrid. Jellyfish Eyes is very definitely a kids’ movie, calling it a “family film” seems unfair when the age cut off is most likely around seven or eight years old but those who meet the (lack of) height requirement are sure to lap it up.

Jellyfish Eyes (めめめのくらげ, Mememe no Kurage) is the feature film debut of the internationally popular Japanese artist, Takashi Murakami. Well known for his cutesy character designs which are as likely to turn up in the world’s best regarded art galleries as they are on a kid’s backpack, Murakami is one of Japan’s most highly regarded art exports. Having unsuccessfully tried to raise interest in the more obvious totally CG animation, Murakami has enlisted the help of gore master Yoshihiro Nishimura for some director’s chair tips in creating a live action/CGI hybrid. Jellyfish Eyes is very definitely a kids’ movie, calling it a “family film” seems unfair when the age cut off is most likely around seven or eight years old but those who meet the (lack of) height requirement are sure to lap it up.