Hibari Misora returns as Oshichi in another adventure for the Edo detective, this time becoming embroiled in a conspiracy against the Shogunate which she continues to serve. By this third instalment in the Detective Hibari series, Hidden Coin (ひばり捕物帖 ふり袖小判, Hibari Torimonocho: Furisode Koban), Oshichi is no longer hiding her noble birth as an esteemed princess, but is living as a singer/law enforcement officer under her “common” name, and upholding the interests of “common” people suffering under “corrupt” samurai oppression but, paradoxically, very much upholding the system which enables it.

The conspiracy in which Oshichi becomes involved this time around is concerned with the plot to overthrow the Shogunate. Rebel forces manage to ambush a convoy carrying tax money to the government, hoping to use the money to buy guns from the Dutch to aid their revolution. As only one of the retainers survives, he will be held responsible for the loss of the money and almost certainly asked to commit ritual suicide, but the Ota clan and most particularly retainer Kennoshin (Kotaro Satomi), are worried about the man’s daughter, Misuzu (Atsuko Nakazato), to whom he was very close. Oshichi becomes involved when she hears of an entire household being murdered and their funds stolen, while a lone pickpocket is found dead with a precious gold coin lying nearby.

Before discovering the crime, Oshichi and her trusty sidekick Gorohachi (Takehiko Kayama) are talking to a kabuki actor who is about to undergo a succession ceremony which will cost a significant amount of money – 1000 Ryo. Gorohachi is mystified, wondering how many years he’d have to work in order to find that kind of money, while the two pickpockets outside wonder something much the same. The older of the two, Oshima (Keiko Yukishiro), wants to make sure the actor gets his money and has been desperately trying to get in touch with him but he is too snooty to see her. Oshichi starts connecting the dots between the pickpockets and the conspiracy to find a vital clue, but once again is keen to stress that “the law can be merciful too” as she both ensures that Oshima faces justice and allows her to find emotional fulfilment in revealing her true identity and finally seeing the show.

Meanwhile, despite outwardly dressing in manly, action friendly outfits, this Oshichi is one more romantically inclined, fretting over the fate of her brother’s retainer Hyoma (Chiyonosuke Azuma) who, she thinks, has left his employ and become a drunkard. The drunken downward spiral of his life turns out to be a kind of undercover assignment, but provokes a little jealousy in Oshichi as she sees him “protecting” other women at a nearby restaurant, one of whom turns out to be Misuzu who holds a few more pieces of the puzzle. Vowing to save Misuzu and stop the conspiracy, Oshichi adopts a male persona complete with top knotted wig and takes on an entire boatload of sailors who stupidly tell her that they’re shipping out that very night.

Oshichi rescues Misuzu and gets the money back, saving her father and “restoring” the status quo, but it’s difficult to see which side she should be on in this fight. As Gorohachi perhaps implies, it’s not exactly fair or responsible for the samurai class to be hoarding all these vast amounts of money, or for it to be necessary to spend the annual salaries of several ordinary people on an extravagant celebration for an actor’s promotion. We’re told that the rebels are “evil” and villainous, and they do indeed seem to be cruel and self-interested, willing to sacrifice anyone and everyone to achieve their goal, but it’s difficult to argue with the desire to stand up to this inherently oppressive system in which samurai corruption is the expected norm.

Insisting that “the law can be merciful”, Oshichi serves a kind of moral justice, rescuing the innocent Misuzu and saving her wrongfully abused father while unmasking samurai corruption, but she remains a loyal servant of the Shogunate and a part of the system into which she was born. Oshichi has been permitted escape from her own oppression thanks to her “compassionate” brother who has allowed her to live freely in the city rather than pressuring her to marry and conform to the feminine norm, but living outside it herself seemingly has no sympathy for those who wish to reform the system and seeks only to preserve it. Having successfully solved the mystery, she reassumes her femininity and retreats into the cheerful festival atmosphere arm in arm with a clean shaven Hyoma finally embracing her romantic dream in an Edo freed from immediate strife.

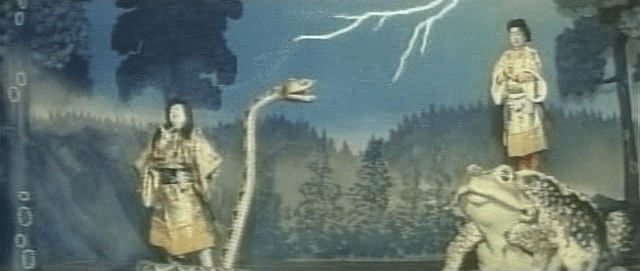

Short clip (no subtitles)

In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not.

In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not. As you read the words “adapted from the novel by Kanae Minato” you know that however cute and cuddly the blurb on the back may make it sound, there will be pain and suffering at its foundation. So it is with A Chorus of Angels (北のカナリアたち, Kita no Kanariatachi) which sells itself as a kind of mini-take on Twenty-Four Eyes (“Twelve Eyes” – if you will) as a middle aged former school mistress meets up with her six former charges only to discover that her own actions have cast an irrevocable shadow over the very sunlight she was determined to shine on their otherwise troubled young lives.

As you read the words “adapted from the novel by Kanae Minato” you know that however cute and cuddly the blurb on the back may make it sound, there will be pain and suffering at its foundation. So it is with A Chorus of Angels (北のカナリアたち, Kita no Kanariatachi) which sells itself as a kind of mini-take on Twenty-Four Eyes (“Twelve Eyes” – if you will) as a middle aged former school mistress meets up with her six former charges only to discover that her own actions have cast an irrevocable shadow over the very sunlight she was determined to shine on their otherwise troubled young lives.