“Isn’t this style called surrealism?” a little girl asks, watching a WWII GI giving John Ford’s Monument Valley a post-modern makeover depicting John Lennon and a Martian in preparation for a live concert by hip girlband ZELDA. Arriving at the beginning of the Bubble era, Naoto Yamakawa’s 35mm commercial feature debut The New Morning of Billy the Kid (ビリィ★ザ★キッドの新しい夜明け, Billy the Kid no Atarashii Yoake) was the first film to be produced by the entertainment arm of department store chain Parco (along with record label Vap) which also distributed and draws inspiration from several stories by genre pioneer Genichiro Takahashi who at one point appears on screen proclaiming singer-songwriter Miyuki Nakajima, a version of whom appears as a character, as one of the three greatest Japanese poets of the age. What transpires is largely surreal, but also a kind of post-modern allegory in which the world is beset by the “anxiety and destruction” of salaryman society.

Yamakawa opens in black and white and in Monument Valley in which only the figure of a young man in a cowboy outfit is in vivid colour while a voiceover from the American President warns that a savage band of gangsters is currently holding the world to ransom. Yet “Monument Valley” turns out to be only an image filling the wall of Bar Slaughterhouse, the cowboy, Billy the Kid (Hiroshi Mikami) stepping out of the painting having lost his horse and apparently in search of a job. The barman (Renji Ishibashi) is reluctant to give him one, after all he has six bodyguards already ranging from the legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi to an anthropomorphism of Directory Enquiries, 104 (LaSalle Ishii). Nevertheless, after threatening to leave (through the front door) Billy asks for a job as a waiter instead in return for food and board while collecting the bounty for any gangsters he kills in the course of his duties.

The bar is in some senses an imaginary place, or at least a space of the imagination, the sanctuary of “construction and creation” where half-remembered pop culture references mingle freely. In that sense it stands in direct opposition to the salaryman reality of Bubble-era Japan where everyone works all the time and the only interests which matter are corporate. Billy takes a liking to a young office lady, “Charlotte Rampling” (Kimie Shingyoji), who complains that she’s overcome with a sense of anxiety in the crushing sameness of her life, often woken by the sound of herself grinding her teeth that is when she’s not too tired to fall asleep. The “gangsters” which eventually crash in (literally) are businessmen and authority figures, one revealing as he raids the till that he’s a dissatisfied civil servant who determined that in order to become the best of the salarymen you need an “interesting” hobby so his is being in a gang. Another later gives a speech remarking again on this sense of inner anxiety that in their soulless desk jobs they’re moving further and further away from this world of “creation and construction”, and that the sacrifice of their individuality has provoked the kind of violent madness which enables this nihilistic “terrorist” enforcement of the corporatist society against which Miyuki (Shigeru Muroi), another of the bodyguards dressed as a retro 50s-style roller diner waitress, rebels through her poetry.

Envisioned as a single set drama (save the bookending Monument Valley scenes apparently filmed on location in Arizona) Yamanaka’s drama is infinitely meta, in part a minor parody of Seven Samurai featuring a Miyamoto Musashi inspired by Kurosawa’s Kyuzo who was himself inspired by Miyamoto Musashi as the seven pop culture bodyguards stand guard over a saloon-style cafe bar beset by the forces of “order” turned modern-day bandits intent on crushing the artistic spirit in order to facilitate the rise of a boring salaryman corporate drone society. Yet for all of its absurdist humour, Harry Callahan (Yoshio Harada) telling a strange story about being a race horse, there is something quietly moving in Yamakawa’s ethereal transitions, the camera gently pulling back as a little girl who wanted to travel is suddenly surrounded by snow or the face of anxious young office lady fading into that of a prairie woman telling a bizarre tale of her life with a venomous snake. Equally a vehicle for girlband ZELDA whose music recurs throughout, the first stage number a hippyish affair set in a summer garden and the second an emo goth aesthetic more suited to what’s about to happen, Yamakawa’s zeitgeisty, post-modern drama is an advocation for the importance of the creative spirit if in another meta touch itself a rebellion against the corporate and consumerist emptiness of Bubble-era Japan.

The New Morning of Billy the Kid streams worldwide 3rd to 5th December with newly prepared English subtitles alongside two of Yamakawa’s earlier shorts courtesy of Matchbox Cine.

Original trailer (English subtitles available via CC button)

Miyuki Nakajima’s debut single, Azami-jo no Lullaby (1975)

ZELDA’s Ogon no Jikan

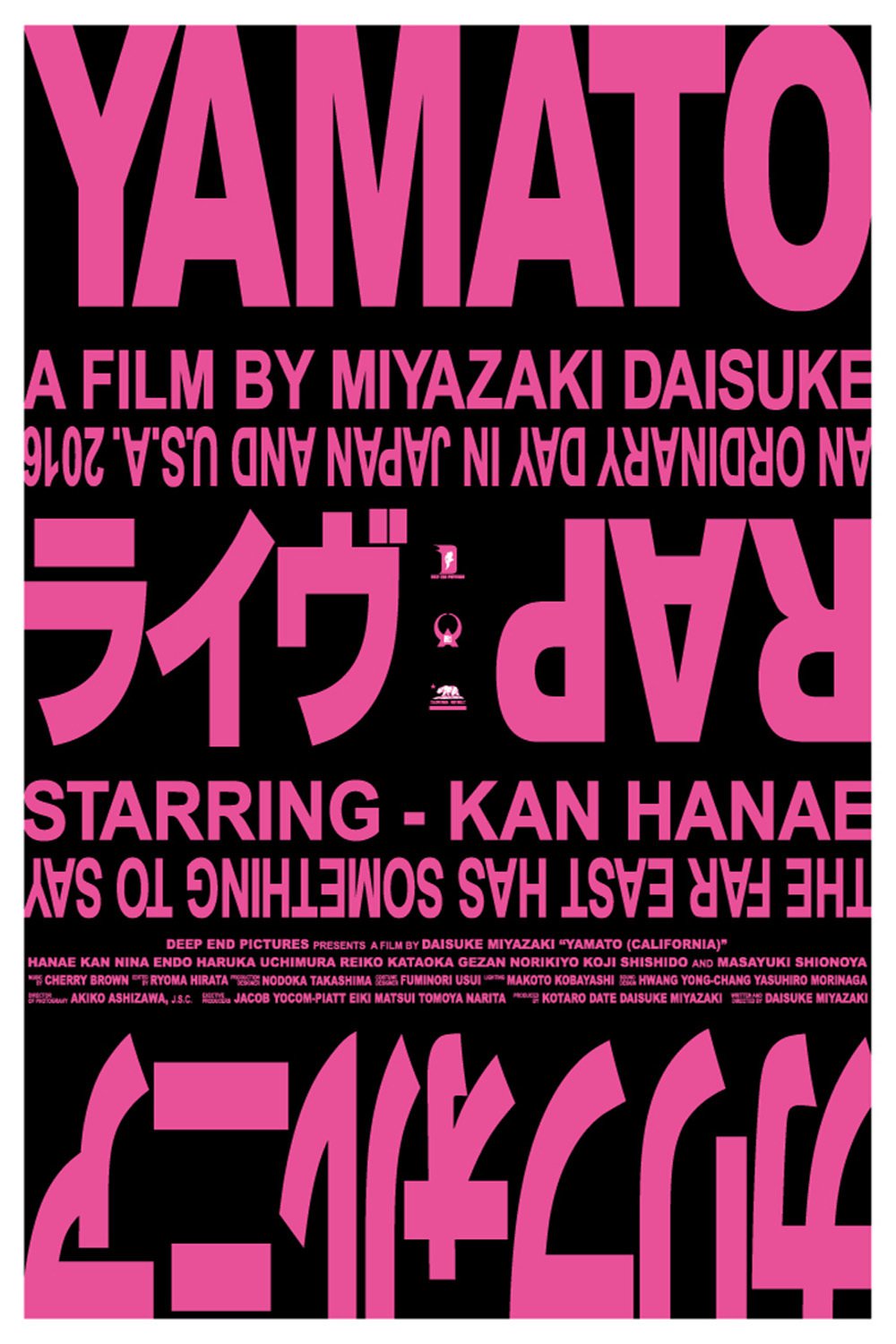

When you think of the American military presence in Japan, your mind naturally turns to Okinawa but the largest mainland US base is actually located not so far from Tokyo in a small Japanese town called Yamato which is also the ancient name for the modern-day country. The US has been a constant presence since the end of the second world war prompting resistance of varying degrees from both left and right either in resentment at perceived complicity in American foreign policy, or the desire to reform the pacifist constitution and rebuild an independent army capable of defending Japan alone. Daisuke Miyazaki’s second feature, Yamato (California) (大和(カリフォルニア) dramatises this long-standing issue through exploring the life of hip-hop enthusiast and Yamato resident Sakura (Hanae Kan) who idolises an art form born of political oppression in a country which she also feels oppresses her as a Japanese citizen living on the other side of the fence from land which technically still belongs to the US government.

When you think of the American military presence in Japan, your mind naturally turns to Okinawa but the largest mainland US base is actually located not so far from Tokyo in a small Japanese town called Yamato which is also the ancient name for the modern-day country. The US has been a constant presence since the end of the second world war prompting resistance of varying degrees from both left and right either in resentment at perceived complicity in American foreign policy, or the desire to reform the pacifist constitution and rebuild an independent army capable of defending Japan alone. Daisuke Miyazaki’s second feature, Yamato (California) (大和(カリフォルニア) dramatises this long-standing issue through exploring the life of hip-hop enthusiast and Yamato resident Sakura (Hanae Kan) who idolises an art form born of political oppression in a country which she also feels oppresses her as a Japanese citizen living on the other side of the fence from land which technically still belongs to the US government.