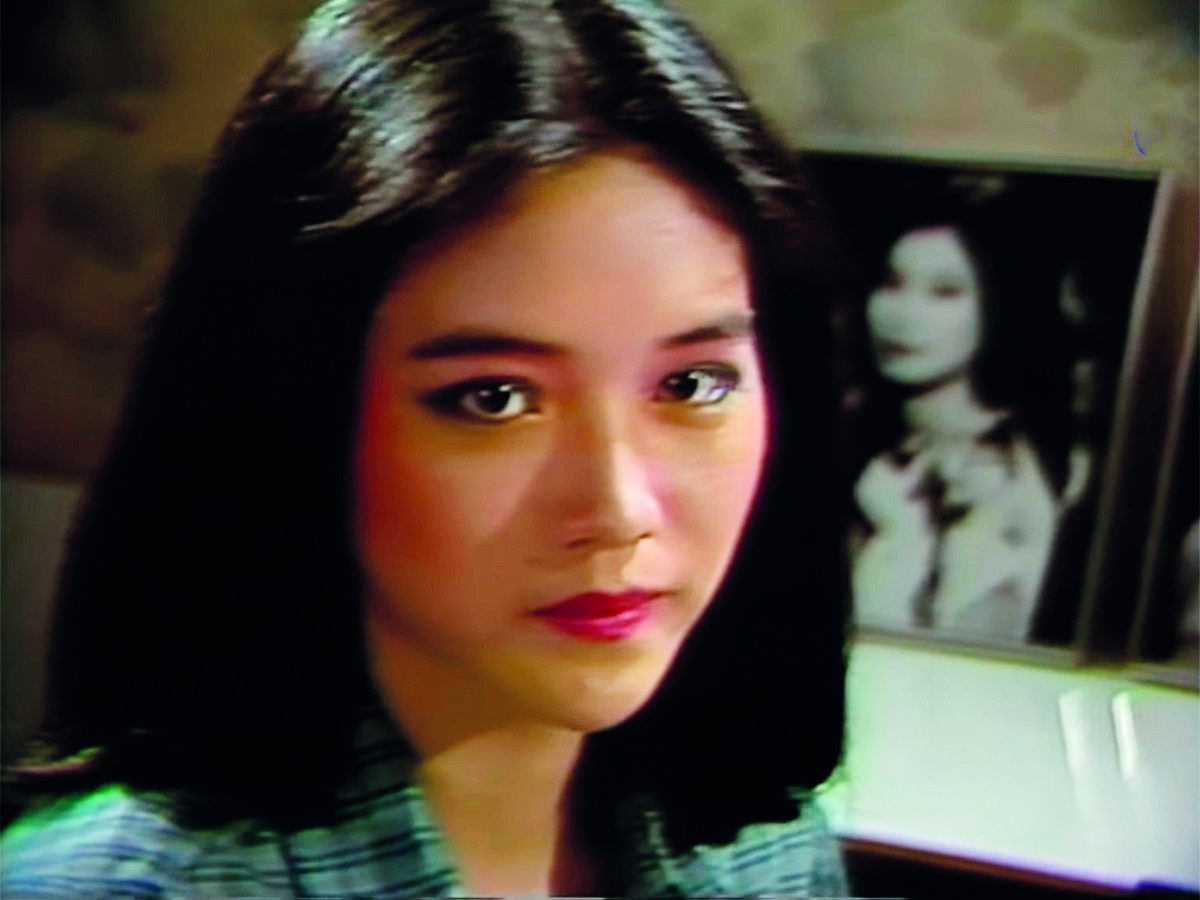

When an already anxious housewife discovers her husband’s affair, she becomes aware of the extent to which she is already trapped by the patriarchal social codes of the contemporary society in Chang Yi’s psychological melodrama, This Love of Mine (我的愛, wǒ de ài). This very messy situation takes on a meta subtext given that This Love of Mine became the last film Chang Yi and his leading actress Loretta Yang would ever make as the pair were hounded out of the Taiwanese film industry after their affair was exposed by the film’s screenwriter, who also happened to be Chang’s wife, the novelist Hsiao Sa.

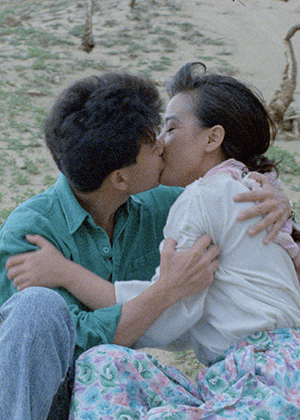

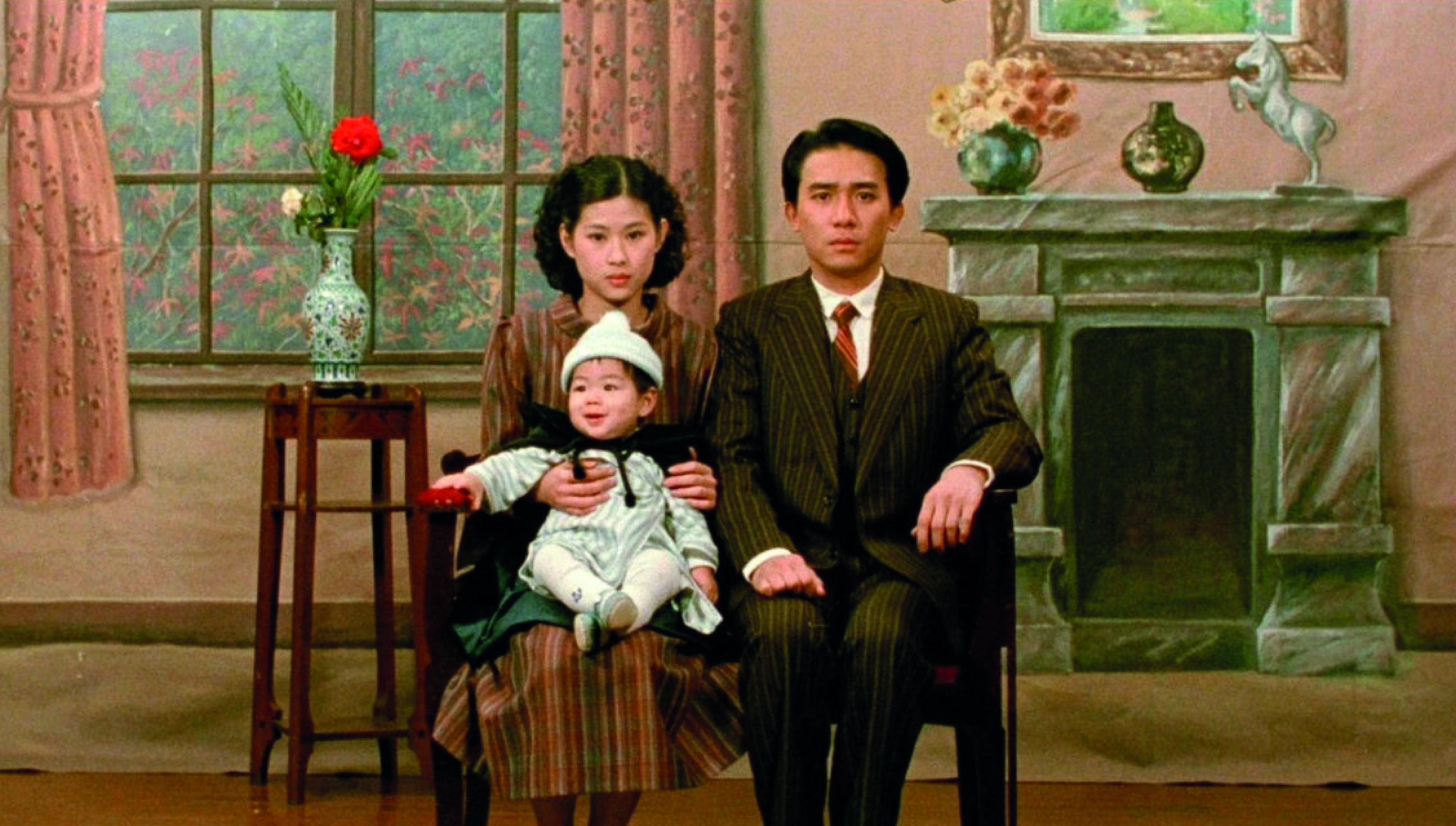

Wei-liang (Loretta Yang Hui-shan) is a typical housewife who’s devoted herself entirely to her husband and children, but she’s approached one day by a childhood friend, An Ping (Elten Ting), who tells her that her husband Wei-ye (Wang Hsia-Chun) is having an affair with her sister, An Ling (Cynthia Khan). The news comes as a shock to her and profoundly destabilises her world. When she confronts Wei-ye, he admits everything but makes no real excuses or promises to end the affair. In fact, he does not really do anything but only seems resigned to the situation as if he had no agency over it.

Wei-liang takes the children to her mother’s and decamps to Kaohsiung to look at apartments but soon realises the impossibility of her situation. She can’t afford the deposit on a flat that she doesn’t like anyway and has no real income nor savings because she poured everything into Wei-liang’s business. Approaching an old friend about a job, she’s told that she’s just too old to re-enter the workforce and will struggle to find anyone who’ll hire her. Even if they do, it won’t be worth her while. The simple fact is that she’s trapped. She’s done everything “right” but has been betrayed and is now left with the realisation that she is powerless. Her husband can do as he pleases because she is economically dependent on him and therefore cannot leave. Wei-liang’s only option is to accept her humiliation and tolerate her husband’s affair.

Her anxieties had begun long before with the early death of her father. Wei-liang resented her mother for remarrying, but she too was faced with this same economic impossibility in the wake of widowhood rather than divorce. Her mother points out that without her stepfather, who does not seem to have treated Wei-liang particularly badly even if he is also a very patriarchal man and expects her mother to wait on him hand and foot, Wei-liang would not have finished her education and what else really could she have done in her situation? It may have been this sense of precarity that most frightened Wei-liang and explains her fixation on the children’s health, panicking about her son eating grapes with the skin on because of the pesticides and insisting on apple juice rather than the sugary drinks and junk food that Wei-ye buys for them.

Wei-liang taking the children to KFC might be the clearest sign of her despair. Taking a razor blade to her hair, she hacks it all off and gives herself a slightly deranged look while directly attacking her femininity. Thereafter she falls into a depression, increasingly unable to see any kind of solution. Wei-ye says that their problem cannot be solved by divorce, but it’s unclear what kind of solution he favours. The implication is that Wei-liang should pretend to ignore his affair and allow him his desires while continuing to play the role of the perfect housewife. An Ling, meanwhile, has her own degree of intensity in insisting that Wei-liang is trapping her husband in obligation and that she is “cruel” for not letting him go so they can be together. Wei-ye hasn’t even really said whether he wants to leave his wife for An Ling or she’s just a casual thing, though it’s unlikely she wants to raise his children too.

Nevertheless, when An Ling says the only way Wei-liang can win is if she dies, it opens the door to something darker as An Ling later manipulatively attempts to take her own life in romantic frustration. It becomes obvious that the only “solution” is that one of these women will have die for there are no other ways out of this situation, especially as Wei-ye refuses to make any decisions or play an active part until finally admitting that the status quo is “unfair” to Wei-liang, which just makes it sound as if he has rejected domesticity in favour of the freedom to pursue his desires with An Ling. Wei-liang points out that she had “desires” too, which were largely unmet by Wei-ye, but that she devoted herself to the family as society expected her to do with nothing left for herself, which might also explain her already fragile mental state. While Wei-liang’s daughter plays with a doll’s house in an echo of the Ibsen play, Wei-liang begins to see that her life has been a lie and her family a kind of illusion. There is only really one way out, and Wei-liang must put herself to sleep in one way or another in order to accommodate herself with it.

This Love of Mine screened as part of the BFI’s Myriad Voices: Reframing Taiwan New Cinema.

Trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)