Ryuichi Hiroki’s career has been oddly varied, but he’s never been one to avoid straying into uncomfortable areas. Adapted from the novel by Asako Yuzuki, The Many Faces of Ito (伊藤くん A to E, Ito-kun A to E) explores the risks and rewards of modern existence through the prismatic viewpoint of five women messed around by the same terrible man as he seems to breeze through life buoyed up by the sense of superiority he gains through their unwavering appreciation. Then again perhaps his air of ultra confidence is yet another mask for his insecurity as he paints every failure as a conscious rejection, sneering superciliously at the desires of others while wilfully negating his own. Our guide, a blocked TV drama scriptwriter, may have imagined this entire scenario as she attempts to break through her own sense of painful inertia but it remains true that the world she inhabits is far from kind to women seeking the key to their own destinies.

Ryuichi Hiroki’s career has been oddly varied, but he’s never been one to avoid straying into uncomfortable areas. Adapted from the novel by Asako Yuzuki, The Many Faces of Ito (伊藤くん A to E, Ito-kun A to E) explores the risks and rewards of modern existence through the prismatic viewpoint of five women messed around by the same terrible man as he seems to breeze through life buoyed up by the sense of superiority he gains through their unwavering appreciation. Then again perhaps his air of ultra confidence is yet another mask for his insecurity as he paints every failure as a conscious rejection, sneering superciliously at the desires of others while wilfully negating his own. Our guide, a blocked TV drama scriptwriter, may have imagined this entire scenario as she attempts to break through her own sense of painful inertia but it remains true that the world she inhabits is far from kind to women seeking the key to their own destinies.

32-year-old Rio (Fumino Kimura) won a scriptwriting competition which developed into a top TV hit some years previously but has struggled to replicate her success and now makes her living teaching screenwriting and acting as an expert on love for women captivated by the idealised romance of her debut “Tokyo Doll House”. Her longterm editor/producer (and former lover but that’s a problem we’ll get to later) encourages her to mine her romance sessions for possible material through interviewing women with unusual romantic dilemmas on the pretext of helping them find a way out. Rio, now jaded and cynical, is of a mind to make money from other people’s misery and the advice she gives is less in service of her clients and more in that of the story as she tries to engineer “naturalistic” drama but as in all things, her writing becomes increasingly personal and she is in effect in dialogue with herself.

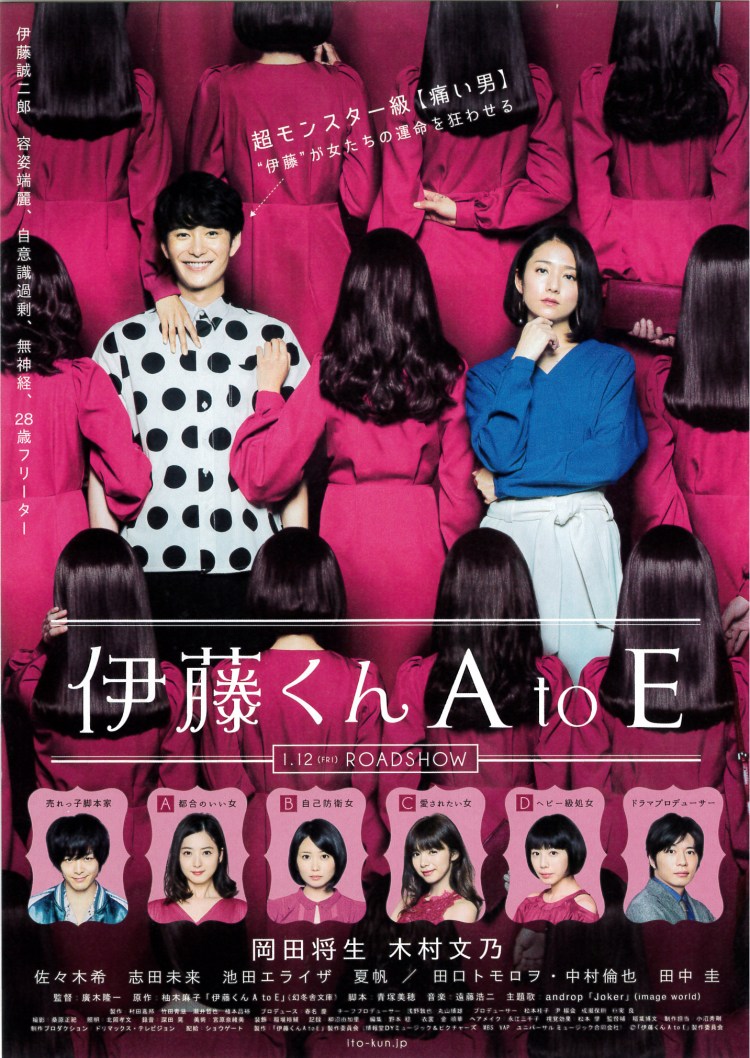

Unbeknownst to Rio, each of the four women she decides to interview is involved with the same man – Ito (Masaki Okada), who is, because coincidence is real, a student in her screenwriting class. With his patterned black and white shirts and handsome yet somehow anonymous appearance, Ito is earnest but superior, shifting from over eager puppy to dangerously possessive stalker. 28-year-old Tomomi (Nozomi Sasaki) has been carrying a torch for him for five years longing for an intimacy that will never develop while Ito insensitively tells her about his crush on a workplace colleague, Shuko (Mirai Shida). Shuko is in no way interested in his advances but Ito refuses to take no for an answer, eventually forcing her to leave the company because of his constant harassment. Wounded, he retreats to university “friend” Miki (Kaho) who he knows has been nursing a long time crush and is shy and naive enough for him to push around without much resistance. Luckily (in one sense) Miki has a devoted roommate, Satoko (Elaiza Ikeda), who is keen to look out for her friend but there is perhaps more to this relationship than meets the eye and Satoko’s jealously eventually pulls her too into Ito’s web of romantic destruction.

The question Rio finds herself asking if each of these women, and she herself in her failure to get over the betrayal of her producer Tamura (Kei Tanaka) who eventually broke up with her to marry someone else, is in a sense complicit in their own inability to move forward. It’s almost as if their collective sense of low self-esteem and fear of rejection has conjured up its own mythical monster in the figure of Ito who displays just about every male failing on offer. He uses and abuses and when rejected proudly states that he never wanted that anyway because he’s simply far too good for whatever it is that you might prize. Yet through battling his cruelty and emotional violence, each of the women is able to cut straight through to the origin of all their problems, correctly identifying what it is that ails them and committing to moving forward in spite of it even if the part of themselves they most feared was the one the saw mirrored in Ito’s insecurities.

The “battle” between Ito and Rio comes out as a draw which sees them both lose but only provokes a final confrontation which is as much with Rio herself as it is with the Itos of the world. Ito rejects his failure, sneers at the TV industry and claims to have loftier goals but Rio has figured him out by now and correctly assesses that his life philosophy is to back away from the fight to avoid the humiliation of losing. Pushed by the unexpectedly profound interventions of fellow writer KazuKen (Tomoya Nakamura) who reminds her that she was once a writer unafraid to bare her soul, Rio realises that a life without risk is mere emptiness and the soulless (non)existence of a man like Ito is no way to live. To be alive to is open yourself up to pain, but if you refuse to engage in fear of getting hurt you might as well be dead and if what you want is to make art you’ll have to lift the lid on all that personal suffering or you’ll never be able to connect. Each of our timid ladies finds themselves ready to stand tall, no longer willing to afford the likes of Ito the esteem which allows him to sail on through papering over his lack of self-confidence by sapping all of theirs. The masks are off, and the game is on.

Currently streaming on Netflix in most territories along with the companion TV drama.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

A relatively rare phenomenon, a lucid dream is one in which the dreamer is aware they are asleep and “awake” enough to influence the outcome. Rather than using the ability to probe some kind of existential question, Korean science fiction thriller Lucid Dream (루시드 드림) focusses on the evidence gathering possibilities, going one step further than hypnotic regression to revisit old memories and zoom in on previously missed details.

A relatively rare phenomenon, a lucid dream is one in which the dreamer is aware they are asleep and “awake” enough to influence the outcome. Rather than using the ability to probe some kind of existential question, Korean science fiction thriller Lucid Dream (루시드 드림) focusses on the evidence gathering possibilities, going one step further than hypnotic regression to revisit old memories and zoom in on previously missed details.