Listening cafes are a phenomenon particular to Japan in which the music is the draw rather than the quality of whatever refreshments are available. Indeed, as Nick Dwyer and Tu Neill’s documentary A Century in Sound (百年の音色, Hyakunen no neiro) makes plain, they are spaces of community and identity in which people with similar tastes come together even if, as at classical music cafe Lion, they sit in silence to better absorb the music. Exploring three such cafes which are themselves a dying breed, the film also examines Japan’s complicated 20th century history and the shifting tastes that accompanied it.

This is evident in the first cafe visited, Cafe Lion, which opened in 1926 and catered to a then new interest in European classical music which in Japan was viewed as something new and exciting. The nation was still emerging from Meiji-era transition and at that time, before the war, entering a moment of fierce internationalism and creativity. The current manager is in her 80s and relates her own memories of another Tokyo before the fire bombing along with the ways the city changed afterwards. Cafe Lion was among the first buildings to be rebuilt and they pride themselves on the quality of their sound system, even deciding to stop serving food because it was considered too noisy and got in the way of the customers’ ability to hear the music. Her son will be taking over the business, so she’s hopeful that this tradition will survive and they’ll be able to continue spreading the love of classical music in the wider community.

The reason these spaces originated was that in the beginning records and sound equipment were expensive so people couldn’t afford to buy their own and would request music they wanted to hear at a cafe instead. Jazz Kissa Eigakan didn’t open until 1978, but though it may have arrived earlier, the owner, Yoshida, attributes the popularity of jazz to a desire for freedom in the post-war society as exemplified by the protests against the security treaty with the Americans and subsequent anti-Vietnam War movement. A former film director, he found the same energy in the Japanese New Wave and opened the cafe to share his love of jazz and film even going so far as making it his life’s work to construct his own sound system to get the best possible sound for his customers that won’t leave them feeling tired or overwhelmed. He also hosts film screenings demonstrating the various ways these spaces have become community hubs that provide a refuge for people with similar interests along with a place to relax and be welcomed in an otherwise hectic city.

That seems to be the draw for Atsuko, a regular at rock music cafe Bird Song which mainly plays Japanese music from the 70s and 80s. In her teenage years, she’d been a frequent visitor to famed rock cafe Blackhawk before going travelling and then settling down to have a family. Now regretting that she gave up her love of music, she’s returned to Bird Song to rediscover it along with another community of like-minded regulars. While Yoshida discusses the era of the student protests, the owner of Bird Song cites Happy End’s 1971 album as a turning point in not only in Japanese music but culturally in moving towards the post-Asama-Sanso society and the consumerist victory that led to the Bubble Era. He posits City Pop as the sound of consumerism and while looking back on his time as an ad exec in the era of high prosperity does not appear to think they were particularly good times or at least that they lacked a kind of spirituality that his customers are looking to rediscover in music.

Dwyer and Neill make good use stock footage and films as well as artful composition to compensate for the talking heads while fully conveying the richness and warmth of these spaces along with their welcoming qualities. Though it’s obviously much easier now to access music wherever and whenever one wants, the cafes provide an optimal listening environment that no home system can replicate while simultaneously providing a place where people can come together and shut out the outside world. Though they may be dying out in a society driven by convenience, the owner of Bird Song has to work a second job as a security guard just to keep the lights on, the cafes represent the best of what a city can be in recreating, as one customer describes it, a village mentality of care and community built on the back of a love of music.

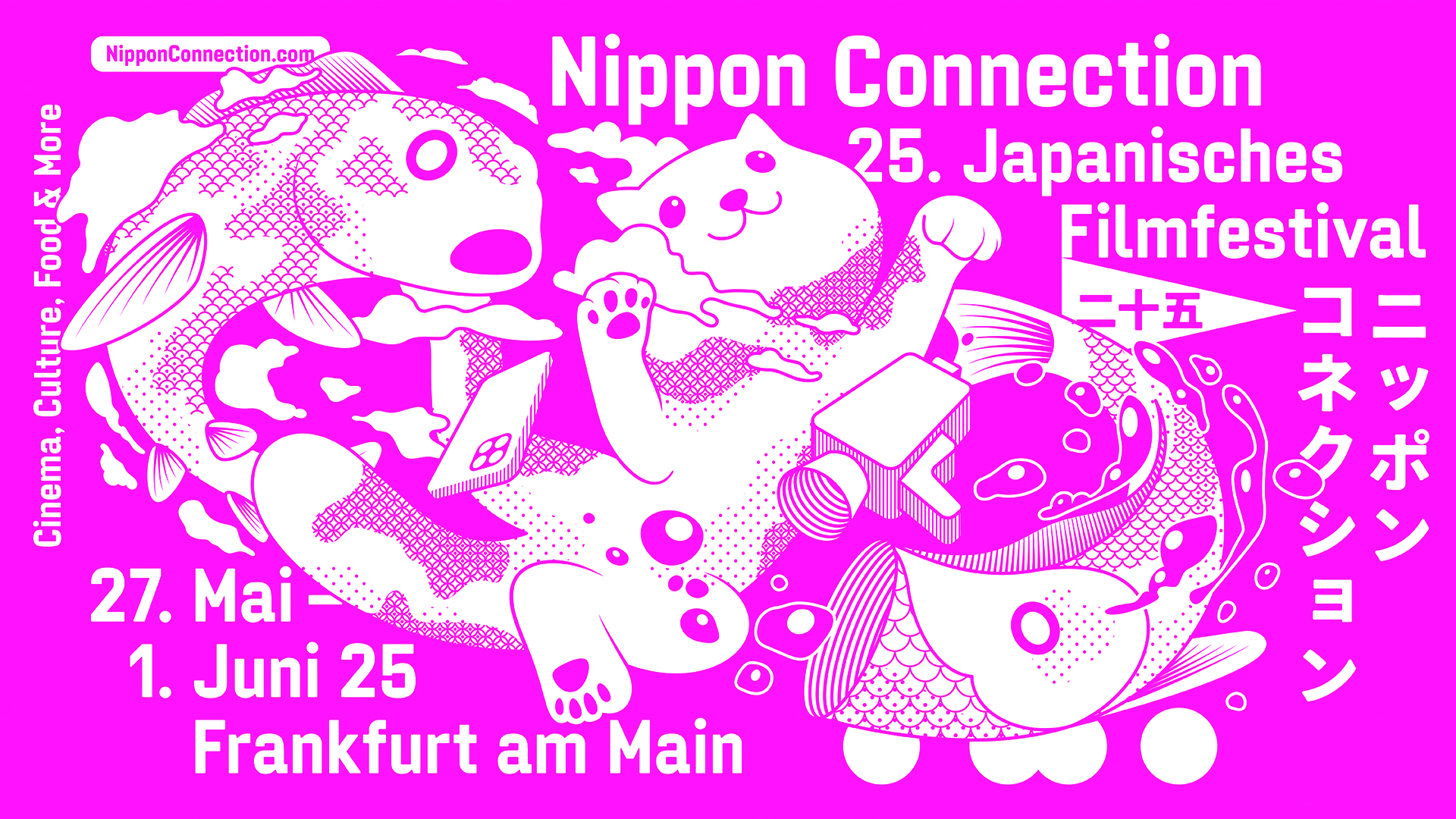

A Century in Sound Escape screened as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Trailer (English subtitles)