A true patriot squares off against a series of duplicitous nationalists in Norifumi Suzuki’s Red Peony Gambler spin-off, Silk Hat Boss (シルクハットの大親分, Silk Hat no Oooyabun) starring Tomisaburo Wakayama as top hat-wearing yakuza Komatora. Set in the world of 1905 in which Japan had just emerged victorious from the Russo-Japanese war, the film on one level attacks the rising militarism of late Meiji in which corrupt and arrogant military officers collude with venal yakuza to further the course of empire while lining their own pockets, but stops short of rejecting it outright.

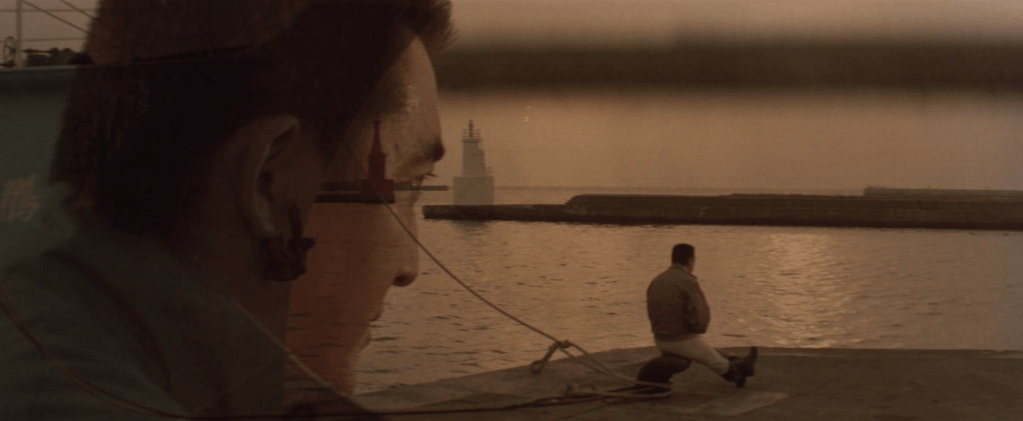

Kumatora is about to return home in glory after taking his guys to the front to defeat the Russians and is expecting to receive a hero’s welcome when the boat docks in Kobe. Unfortunately, he is met only by his sister and an underling, Hansuke, who he immediately berates for the affront of having grown a magnificent moustache in his absence which is even bigger than his own. It turns out that evil yakuza rival Chindai has stolen all the credit for the work done by those like Kumatora and the ordinary foot soldiers who lost their lives defending Japan’s interests.

Chindai has teamed up with corrupt military officer Kito who wastes no time throwing his weight around. Having fallen her during a brawl but been rebuffed, Kumatora searches for Osakan geisha Choko only to find her running away after Kito tried to assault her. Running around in his underwear, Kito rudely demands that Kumatora “return” Choko to him, but true to form Kumatora only tells him that he’s being unreasonable and the choice of whether to return or not belongs to Choko herself. Something similar occurs when Kumatora visits the family of a fallen comrade and discovers that his wife has been forced into sex work while the daughter, Satsuki, is seriously ill. Noticing the pock marks on her face which remind him of his own, Kumatora immediately decides to take the girl to a hospital at his own expense and, in fact, throws Kita out of a rickshaw in which he was riding because the girl’s need is greater.

Kumatora is, perhaps unexpectedly, a great defender of the rights of women. After taking his guys to a brothel, he finds out that the girl assigned to him is only 14 and ends up cleaning her ears and singing a lullaby. Eventually he discovers that Chindai and Kita have been rounding up sex workers and tricking other women into sexual slavery with the intention of trafficking them and resolves to free all of them while looking for Satsuki’s mother to let her know she no longer needs to work in the red light district. Of course, Kumatora is very much in the throes of his unrequited love for Red Peony Gambler Oryu (Junko Fuji), running back to his lodgings mistakenly thinking she’s in town, but partially rejects Choko’s affections after she becomes besotted with him because he thinks it’s unfair to ask a woman to become the wife of a yakuza who might after all die any day.

Kumatora is also a fierce defender of his men, ceremoniously handing each of them a condom at the brothel and reminding them to stay safe before they head off with the women whom he has already rather comically inspected. He is very clear that the victory over the Russians was bought with the lives of ordinary workers who should be fairly rewarded with their share of the glory rather than allowing men like Chindai to exploit their heroism for their own gain. Kumatora finds an ally in good general Matsumoto who hands him a letter he can’t read from a general he admired who calls him the ideal Japanese man for his bravery and fighting spirit, but is as expected targeted by Kito and Chindai who are only interested in lining their own pockets. What it boils down to is that Kumatora is good because his patriotism is genuine while Kito and Chinda are bad because their nationalism is self-serving which does quite uncomfortably suggest that imperialism itself is not an issue only how it’s progressed.

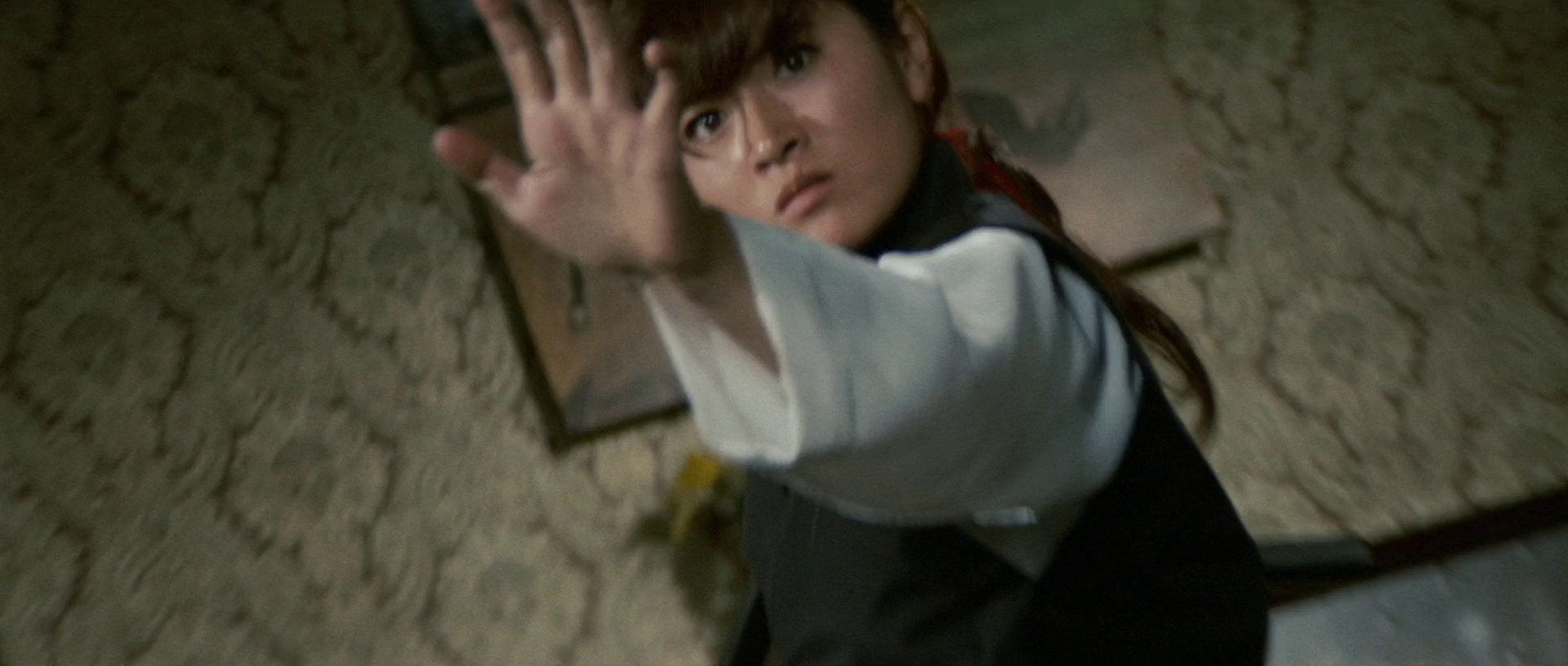

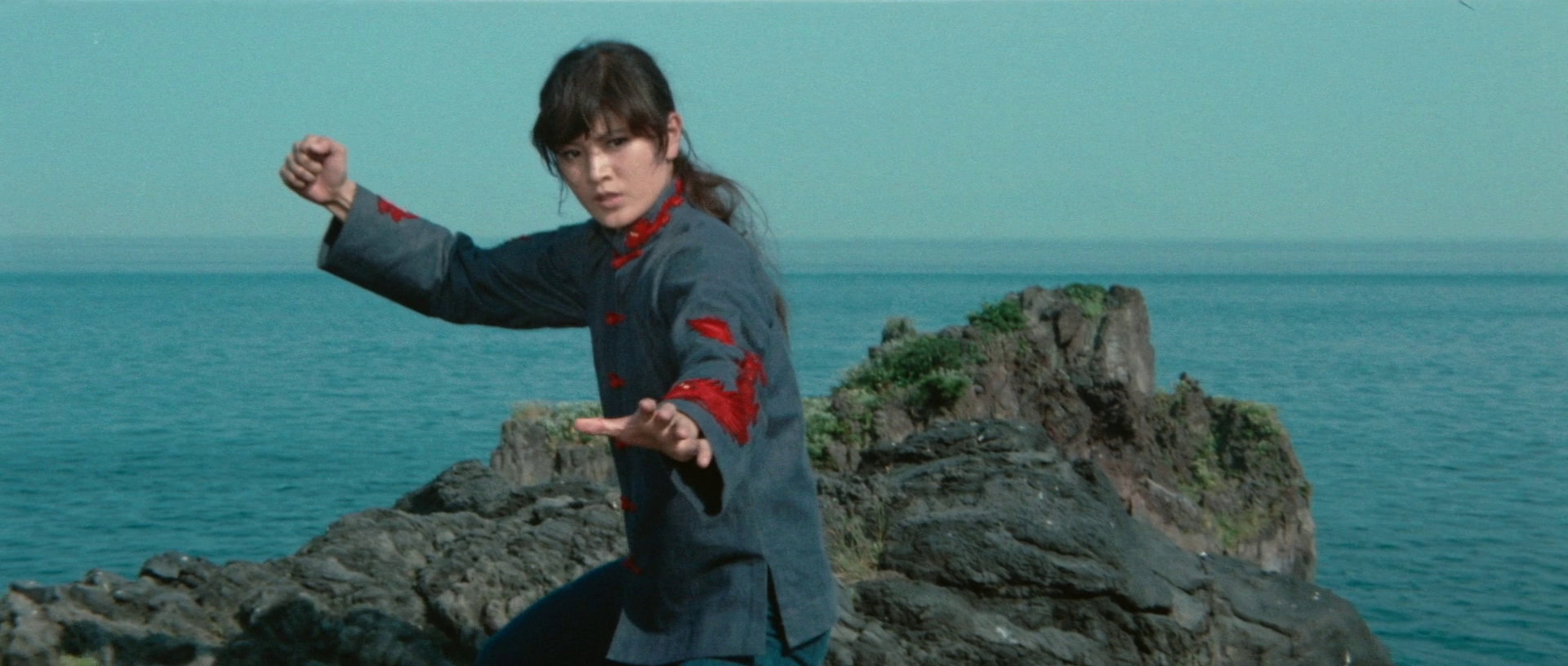

In any case, the corrupt officers are finally dealt a crushing blow by a resurgent Kumatora along with a little help from Oryu herself who eventually turns up to save the day in the bloody showdown which ends the film. Slightly absurdist in tone, the Silk Hat Boss has its fair share of offbeat humour beginning with Kumatora wearing his top hat in the bath and jokingly comparing various generals’ penis sizes to that of a loofah but is undeniably endearing in its hero’s guileless goodness.