Write what you know, the old adage goes, but can you really write about love if you’ve never been in it? The debut feature from Crisanto Aquino, Write About Love concerns itself not only with romance but with love in a wider sense as mediated through the act of creativity. Two writers are forced into an awkward collaboration working in some senses at cross purposes but eventually find common ground as their shared endeavour pushes them towards acts of self interrogation as they attempt to write a sincere romance with an ending that satisfies all.

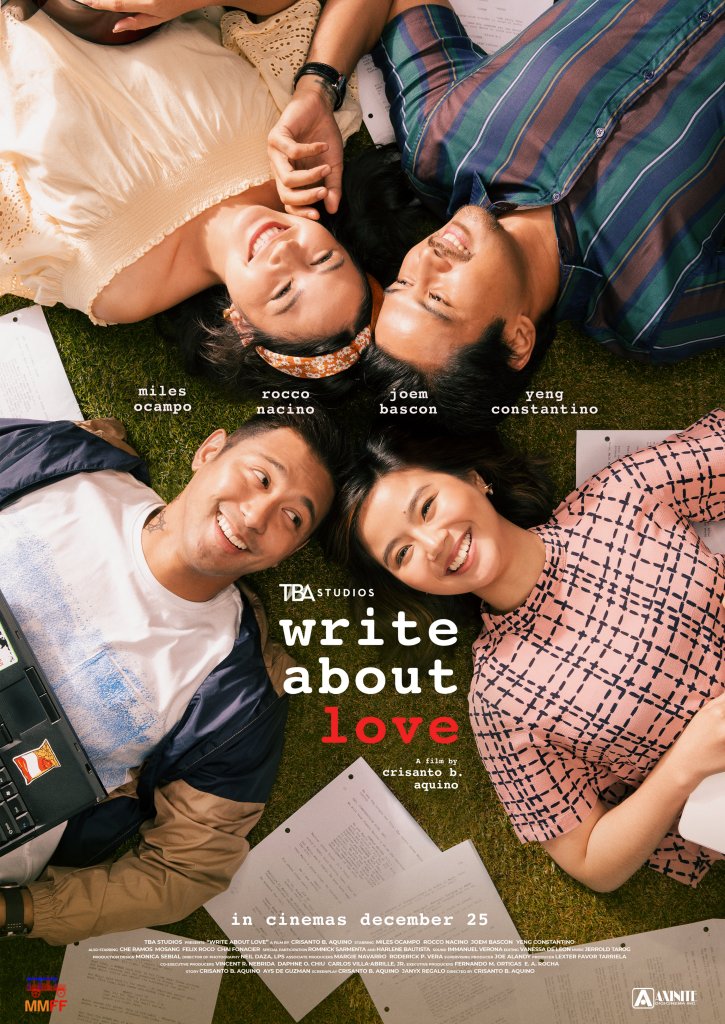

Credited only as “female writer” (Miles Ocampo), a young woman obsessed with rom-coms successfully pitches one of her own titled “Just Us” to a major studio. Though they like her ideas, the suits call her back in a few days later and express concern that her scenario is too similar to an upcoming movie from a rival studio. Rather than a traditional meet-cute rom-com, they want her to focus on what came next, not the story of how they got together but a serious relationship drama about all the boring bits of being in love. To help her out, they’ve decided to team her up with an experienced “indie” screenwriter (Rocco Nacino), and have given the pair one month to thrash out a first draft.

Of course, things get off to a bumpy start. She’s very “mainstream”, He’s quite cynical, which might make for an interesting dynamic if they weren’t constantly clashing on a personal level. He pushes his experience, She pushes her earnestness. Still, they begin to become closer writing the story of Joyce (Yeng Constantino) and Marco (Joem Bascon), an aspiring musician and a company man who meet and fall in love but find that life gets in the way of their grand romance. The pair decide to structure their drama around various anniversaries – 100 days, 200 days, a year etc, during which Joyce and Marco grow apart, discover that they have different priorities, and eventually break up after an intense argument that lays bare Marco’s insecurity and ongoing abandonment issues which lead him to put his foot down over Joyce’s career ambitions in Korea.

Meanwhile, the real lives of the writers begin to influence the drama as they hover on the sidelines observing their fictional romantics and plotting out where they might go next. Despite their intention not to write a “mainstream” romance, they are perfectly happy to play with standard melodrama plot devices like job offers from overseas and terminal illnesses as they try to tell the story of Joyce and Marco, but, it seems, those “plot devices” also come from their lives. He had a longterm relationship end because his lover went abroad and met someone else, while she is romantically naive and still hung up on the failure of her parents’ relationship. In fact, her parents’ meet cute inspired the one in Just Us though she hoped to rewrite their story with a happier ending where her dad didn’t eventually leave them to go back to an old girlfriend.

He asks her if she’s never been in love because she’s afraid of getting hurt, She tells him she’s just not interested, but is eventually forced to deal with her sense of insecurity through accepting the fact that her family is never getting back together. He actually doesn’t tell her much of anything, but is later forced to accept that love is a choice he may have failed to make. We expect that the writers will eventually fall in love while writing the saga of Joyce and Marco, but first they have to discover a few things about themselves, about love, and about suffering. Questioning her mother, She finds out that love is great motivator, prompting you to make decisions good and bad, while He realises that just as in real life you can’t manipulate your characters to force them to do what you want because feelings must be earned to be sincere. Love and pain are inextricable, but love is also an energy which cannot be created or destroyed and endures even after death, according to Her, coming to the conclusion that you need two for a love story and creation is a collaborative effort. Maybe you can’t write yourself out of heartbreak, or give yourself a better ending than life saw fit to give you, but if you’re going to write about love you have to be honest and honest is never easy.

Write About Love was screened as part of this year’s Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)