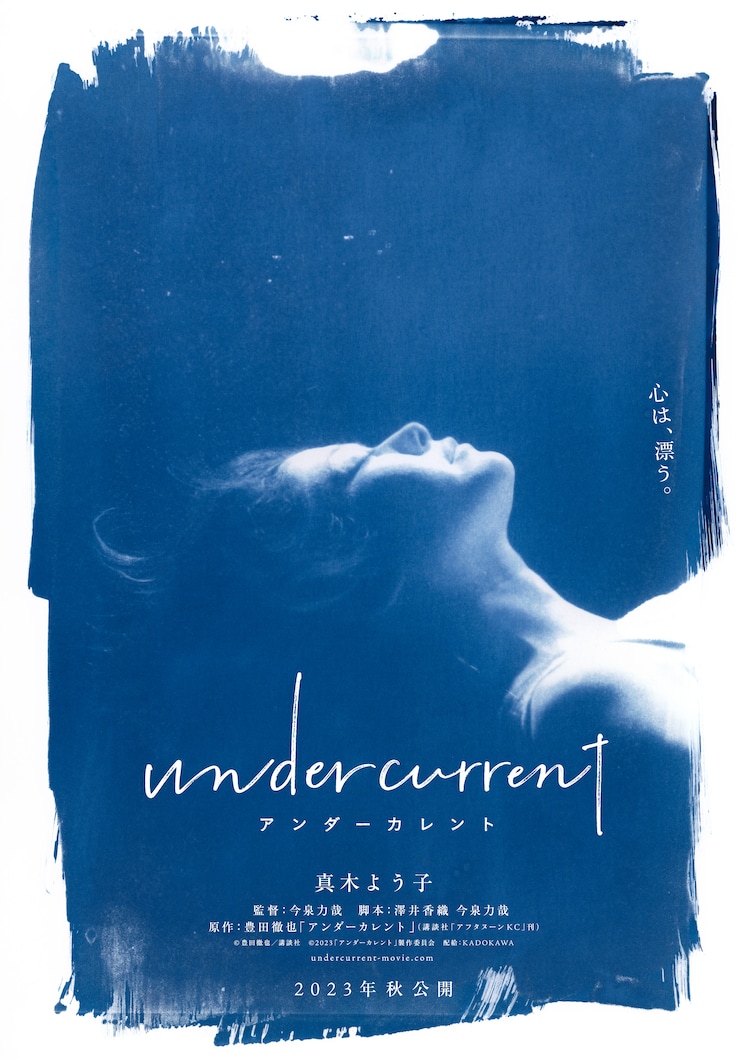

Part way through Rikiya Imaizumi’s adaptation of the Testuyua Toyoda manga Undercurrent (アンダーカレント) a detective asks his client what she thinks it means to “understand” someone. Of course, she doesn’t really have an answer, and the film seems to suggest there isn’t one because we are forever strangers to ourselves let alone anyone else. We do things without knowing why or that somehow surprise us, while the actions of others can an also be be worryingly opaque. But then perhaps you don’t really need to “know” someone in order to “understand” them and as someone else later says perhaps it’s true enough that most people don’t really want the truth but a comforting illusion.

But then Kanae’s (Yoko Maki) illusions aren’t exactly comforting. Her husband of four years Satoru (Eita Nagayama) suddenly disappeared during a work trip a year previously and has not been heard from since. She turns the television off when the news announces details of a decomposing body discovered near a set of electrical pylons, but on another level she’s sure that Satoru is alive and chose to leave her for reasons she can’t understand. Kanae tells a friend that what pains her most is thinking that in the end she wasn’t a person Satoru felt he could share his worries with so she was powerless to help him. Then again, there’s something in Kanae that is equally closed off, a little distant and otherworldly as if she were also putting up a front to keep her true self submerged.

The detective (Lily Franky), whose name is “Yamasaki” yet allows people call him “Yamazaki” because it’s easier for them, says of Satoru that his “cheerful,” ever smiling nature may also have been a kind of masking designed to dissuade people from looking any deeper. Someone else admits that they lied mostly to fit in, be what others wanted them to be, only to be caught out by the gulf between their genuine feelings and and the ever expanding web of their lies. Caught in a kind of suspended animation uncertain if Satoru will ever return and if and how she should continue with her life, Kanae ends up taking in a new assistant at her family bathhouse. Hori (Arata Iura) is the polar opposite of the way her husband is described, silent, soulful and somehow sad. We might be suspicious of him, his arrival seems too coincidental and the way he looks at some children running past in the town perhaps worrying. Yet how can we judge based only on his silence knowing nothing else of his history? Nevertheless, he may understand Kanae much better than anyone would suspect and may be the comforting presence from her recurring nightmares.

In her dreams, she’s plunged into water with a pair of hands around her neck. Unknowingly, Hori asks her if she’s ever really wanted to die and she can’t answer him even if it seems to us that the dreams reflect her desire for death, to be submerged in a sea of forgetfulness. Yet we later learn they come to have another meaning reflecting her long buried trauma and the reason for her own listlessness. These are the undercurrents that run silently through her, waves of guilt and grief that obscure all else. Disappearances have happened around her all life and seem only to increase, another bath house owner seemingly disappearing after a fire having promised to sell her his boiler. Yet through her experiences, she comes to fear them less reflecting that anyone could leave at any moment and that’s alright, as Hori had said nothing’s really forever.

Even so, she regrets that there couldn’t have been more emotional honesty from the beginning then perhaps no one would need to disappear without a word. Confessions are made and the air is cleared. Someone had said that no one wanted the truth, but it seems Kanae has chosen it as perhaps symbolised in her decision to call Yamasaki by his actual name rather than the one he allows people to use because it’s too much trouble to correct them. Aside from his multiple names, Yamasaki is a strange man who holds meetings in karaoke boxes and theme parks though perhaps because he simply thinks Kanae could use a little cheering up. In more ways than one, it’s the ones left behind who are left in the dark, but they may be able to find their way out of it with a little more light and reflection.

Screened as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Ah young love! So beautiful, so complicated, so retrospectively trivial. Intrigue engulfs a group of young Koreans living in Japan, their co-workers, and even their English teacher and her fiancee in Rikiya Imaizumi’s indie youth meets boyband quirky romance movie, Their Distance (知らない、ふたり, Shiranai Futari). The aptly named picture paints a vista of misdirected love, miscommunication and misjudged honesty to show how messy romance can be even when it’s intent on being cute.

Ah young love! So beautiful, so complicated, so retrospectively trivial. Intrigue engulfs a group of young Koreans living in Japan, their co-workers, and even their English teacher and her fiancee in Rikiya Imaizumi’s indie youth meets boyband quirky romance movie, Their Distance (知らない、ふたり, Shiranai Futari). The aptly named picture paints a vista of misdirected love, miscommunication and misjudged honesty to show how messy romance can be even when it’s intent on being cute.