Satoshi Kirishima’s incongruously smiling face was a familiar presence across on the nation for over 40 years until he finally made a deathbed confession revealing his true identity as a man wanted in connection with a series of bombings in the 1970s and that he’d successfully evaded the authorities until the very end of his life. What apparently appealed to director Masao Adachi, a former Japanese Red Army member, was the question of why he chose to come clean rather than enjoy his secret victory by taking the truth to his grave.

That might be a minor irony at the centre of the Escape (逃走, Toso) in that Satoshi (Kanji Furutachi) is essentially in flight from himself only to finally escape from his torment by accepting his original identity. As a young man, Satoshi had been a member of a left-wing cell that wanted to awaken the population at large to the ways Japanese society had not changed in continuing to discriminate against the Ainu, those from the Ryukyu Islands, Koreans and other minorities while modern corporations enact another kind of capitalistic imperialism built on exploitation. It was for this reason that they embarked on a bombing campaign targeting large companies, but due to a miscalculation with the explosives, the bombing of the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Building in 1974 proved more destructive than intended resulting in loss of life.

Satoshi was not directly involved in that bombing which was carried out by another cell but was wanted for allegedly setting up a bomb in the Economic Research Institute of Korea which did not result in any casualties. Details of the real Satoshi’s life during his 40 years on the run are thin on the ground, but Adachi paints him as a man torn apart by internalised conflict and unable to make peace with the sense of guilt he feels for those who killed even if he was not directly responsible. The film’s Japanese title is a kind pun in that it’s a homonym which can mean both “escape” and “struggle” which for Satoshi become one and the same. He’s in flight from his younger self while simultaneously preoccupied with how he can continue the revolution in the name of his friends who were not so lucky. Adachi structures the later part of the film as a kind of self-criticism session as Satoshi engages in various dialogues with himself notably as a Buddhist priest interrogating him about his worldly attachments.

These worldly attachments also obviously separate him from his true calling to revolution including a non-relationship with a woman he meets at a concert venue and is later told has two previous convictions for marriage fraud. Most of the people around him are also leading double lives or harbouring secrets of their own including a man that Satoshi once worked with whom he finds out years later was also another former member of the far left movement living life on the run. The implication is that this sense of isolation and aloneness in wilfully having to suppress his identity became a kind of prison, but that it also liberates Satoshi to a more intensive examination of the self.

To that extent, his escape is also from contemporary Japan and an act of resistance towards an increasingly capitalistic and indifferent society. Hoping to stay below the radar, Satoshi works a series of casual construction jobs chiefly because of their anonymity. There was plenty to be built in this era and jobs like these were plentiful, usually offering basic accommodation in a company dorm. He experiences the hardships of the working man first-hand and lives a life of asceticism in which live music and drinking are his only outlets. “We’re all dying to survive,” he reflects, “trying to go home,” though he no longer has a home to go to and has become estranged from his previous identity. He meditates on fallen comrades who either took their own lives or spent them in prison while convincing himself that he’s continuing the struggle on their behalf even in the act of running away in perfecting his “escape”. Though Adachi’s approach is less sentimental than Banmei Takahashi’s in I am Kirishima, he is not immune to sentiment as in his depiction of Satoshi’s final escape from life as the ultimate form of liberation even as his ghost proclaims he will continue to fight, but nevertheless introduces a meta commentary of self-examination in Satoshi’s constant questioning if his long years of struggle have really been worth it.

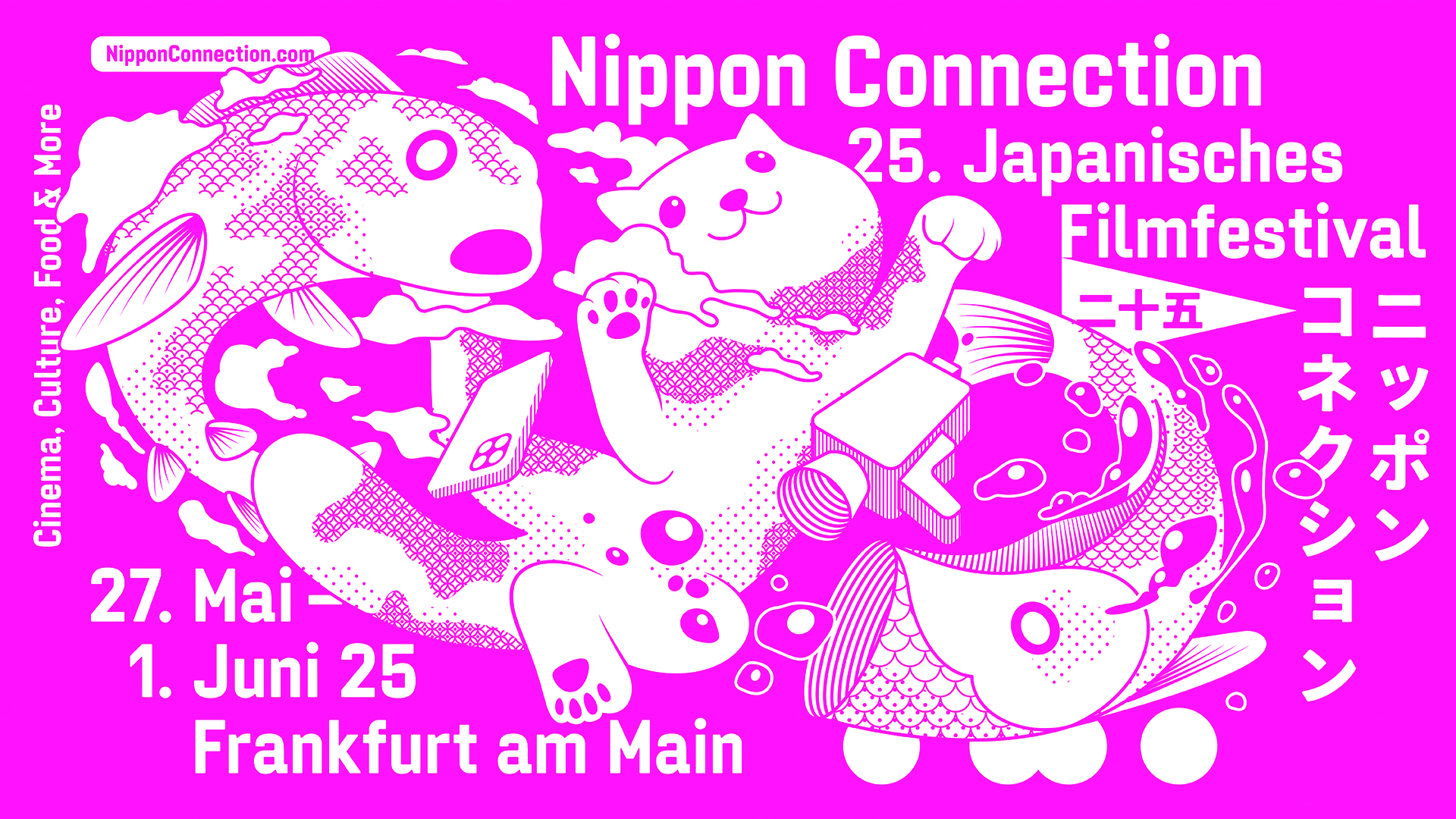

Escape screened as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.