According to hostess bar and real estate mogul Tachibana (Yukiyoshi Ozawa), the secret to living a peaceful, ordinary life is to avoid becoming angry. Though it may not altogether be bad advice in that it’s often best to try to remain calm and reach a rational solution rather than losing one’s temper and acting impetuously, the way he says it is a veiled threat. Leave me alone, he means, and I’ll leave you alone too, otherwise neither of us will know peace again.

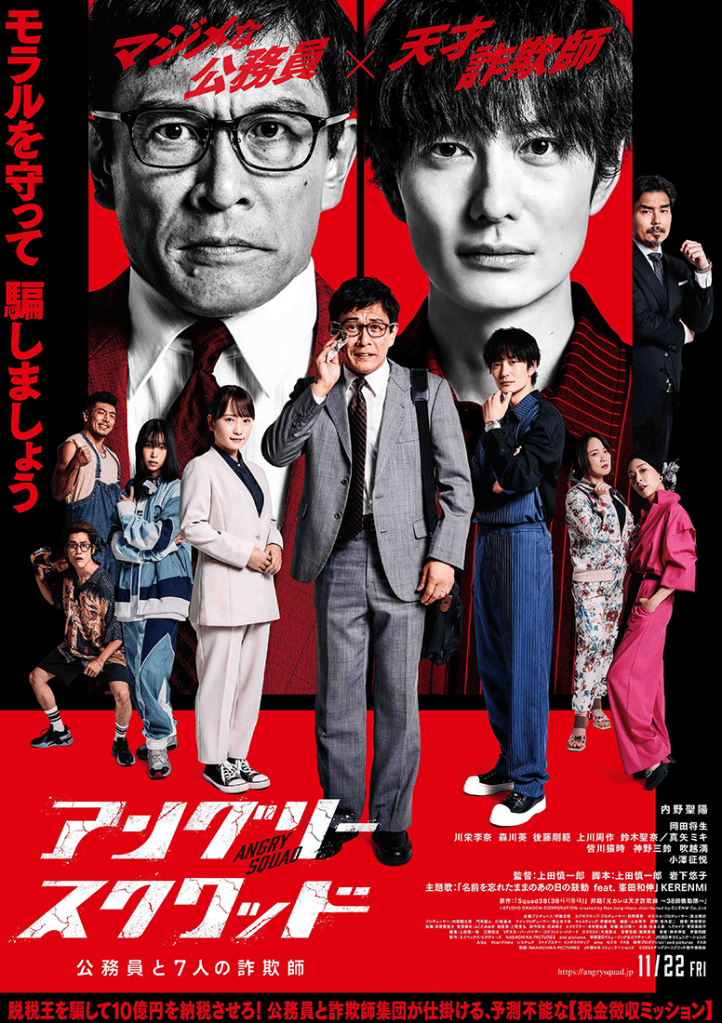

Shinichiro Ueda’s timely heist caper Angry Squad: The Civil Servant and the Seven Swindlers (アングリースクワッド 公務員と7人の詐欺師, Angry Squad: Komuin to 7-nin no Sagishi) makes unlikely heroes of the tax man in exploring the disparities of wealth and power in the contemporary society. Middle-aged tax officer Kumazawa (Seiyo Uchino) is a man cowed by conformity. He’s been doing his job a long time and believes in cracking down on notable evaders, but has also become cynical and if, on one level, aware of the corruption that exists within the system that allows the very wealthy to overcome the rules, he’s content to keep his head down and ignore it. After all, he has responsibilities too with a family to support. He can’t afford to lose his job playing the hero. His much younger and very ambitious colleague Mochizuki (Rina Kawaei) has no such concerns and is willing to take on Tachibana without real fear of the consequences.

Yet at the same time there’s a quiet rage that seems to be simmering in Kumazawa about the compromises he’s continuing to make. He jokingly tells a young woman how to fudge her taxes to claim an eel dinner as a business expense, but knows better than to poke the bear by looking into Tachibana’s tax affairs. When Mochizuki takes him to task, Tachibana comes for him directly by accusing him of using violence and threatening to have him fired unless he apologises and promises never to come after Tachibana again. Conscious of his own financial situation Kumazawa nods along. Mochizuki refuses and has her promotion withdrawn, though she does at least keep her job.

But the thing that really makes Kumazawa angry is that Tachibana didn’t even remember the name of his friend who took his own life after Tachibana framed him for misconduct to get rid of him. It’s this that convinces him to team up with what later seem to be ethical con people who are after Tachibana as a kind of revenge on society that is later revealed to have a personal dimension. Though Kumazawa is conflicted about the idea of committing what amounts to a crime, he accepts that it’s the only way they can ever hope to take Tachibana down. Even his old policeman friend tells him that his boss is chummy with Tachibana so they won’t go after him either suggesting this rot goes right to the top and the super wealthy essentially exist outside the law.

In a funny way, the weapon then becomes mutual solidarity and community action as this disparate group of people who each have a grudge against Tachibana come together to confiscate what he should have paid in taxes to force him to pay his fair share. The fact that his empire is built on hostess bars and is expanding into real estate suggests that his business is already exploitative while he only gets away with it because people don’t get angry enough to stop him. The authorities either take kickbacks, are being blackmailed, or enjoy being a part of his celebrity milieu so they shut down any attempts to ask questions.

This Angry Squad are, however, prepared to play him at his own game harnessing Tachibana’s greed and vanity as weapons against him. As expected, they do so in a very humorous and intricately plotted way as the gang pool their respective strengths to pull off a major heist with a little unexpected help along the way. It turns out that you might need to take an unusual path to make even the tax office see the error of their ways, but it is after all for the fairly noble cause of reminding people that the rules should apply to everyone equally and all should be happy to contribute their fair share for a better run society.

Angry Squad: The Civil Servant and the Seven Swindlers screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (English subtitles)