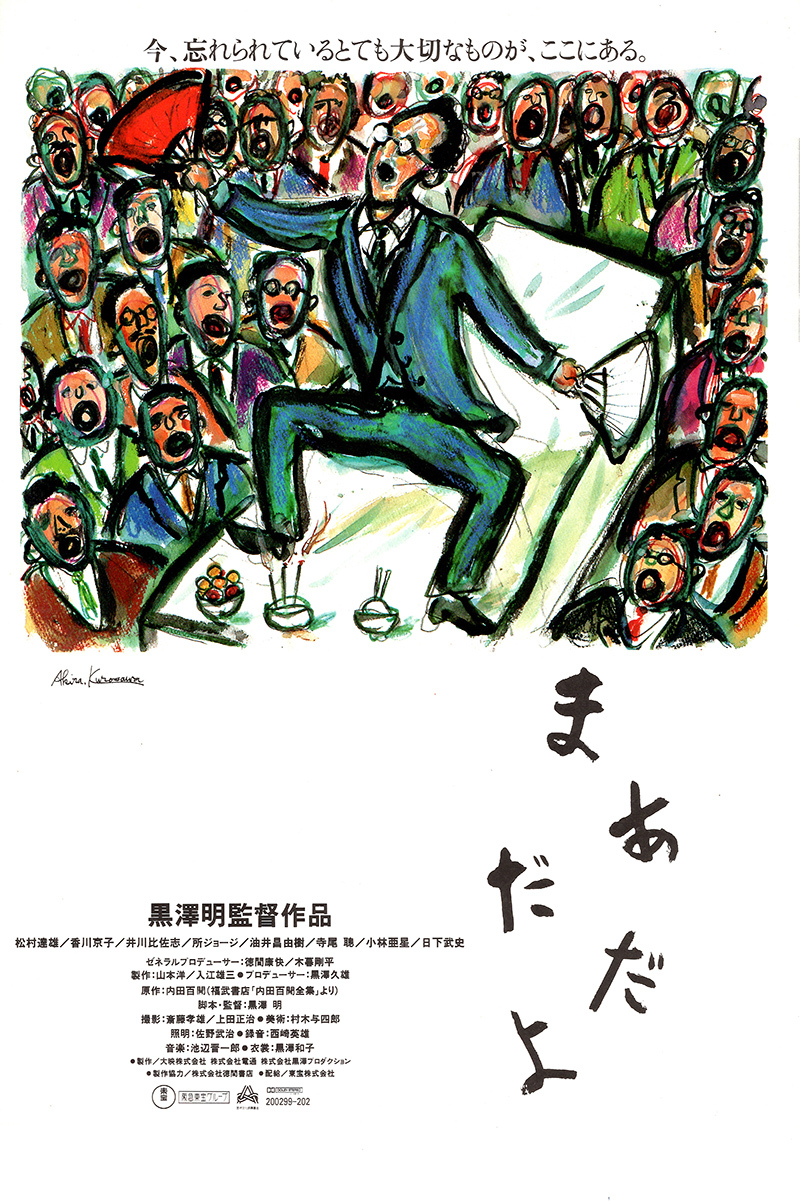

It’s tempting to read Akira Kurosawa’s final film Madadayo (まあだだよ) as a kind of valediction, though he may not have thought of it as a “final” film and if he had, it would have been ironically for film’s title means “not yet” and thematically hints at a desire on hold to a life that is admittedly fleeting. Much of the film is indeed bound up with transience and the difficulties of accepting it, but it’s also a humorous tale of a man who was “pure gold” and managed to maintain his childish heart even into his 77th year.

Inspired by the life of the writer Hyakka Uchida (Tatsuo Matsumura), the film rather curiously opens with his retirement as he abandons his teaching position to pursue writing full-time much to the disappointment of his doting students. The relationship between Uchida and the boys he taught is at the heart of the film, for much like Mr Chips he had no children of his own and is cared for in his old age by a collection of old boys who almost venerate him as if he were something precious which cannot be allowed to slip from the world. Soon after his retirement, Uchida achieves his Kanreki, that is his 60th birthday or the completion of one cycle of the Chinese zodiac which is also the beginning of a second never to be completed round, which some consider as a second childhood or the beginning of old age.

Uchida is indeed childishly innocent and generally lighthearted forever making incredibly silly puns and approaching even potentially serious situations with good humour. When his wife remarks that the rent may be reasonable on their new home because it is unlucky and prone to being burgled, Uchida simply puts up a series of signs directing thieves to the “burglars entrance” through the “burglars corridor” to the “burglars lounge” and “burglars exit” reasoning any potential robber would find the situation so odd as to want to leave as soon as possible. The house does turn out to be unlucky in a sense as it is burned down during the fire bombing of Tokyo leaving the Uchida and his wife to move into a tiny shack on the grounds of a ruined mansion.

Signs of a sense of irony and an underlying darkness are, however, present in his improvised version of a march he would have taught the students during the years of militarism on which he comments on the disillusioning realities of new era of “democracy” under the Occupation ruled by bribery and corruption. The students decide to hold a birthday party for the professor they christen the “Not Yet Fest”, taking the lines from a child’s game of hide and seek to ironically ask if he’s ready to throw in the towel first, actually featuring a performance of his funeral which might seem insensitive but Uchida can be relied upon to see the funny side. During the party the former students give various speeches, one announcing he will recite the names of all the stations from one end of the country to the other, but no one really pays very much attention to them. The students even track on a large white dinner plate during a children’s song about the moon to hold behind Uchida’s head as if he were a buddha achieving enlightenment.

Yet the crisis comes when, shortly after the students buy Uchida and his wife a new house to live in, their beloved cat Alley disappears, plunging the professor into a well of existential despair that leaves him unable to sleep or eat. The depths of his sorrow perhaps hint at his childish sincerity, though there is an undeniable poignancy in the attachment of the childless couple to this cat that chose them as its family. Despite the best efforts of the students along with the local community, Alley never returns though the professor and his wife learn to love a new cat who like Alley wandered into their garden and found a home. As in the poem that inspires Uchida in his “ascetic” life in the hut, life is an ever-flowing river. The waves of students that flowed through his classroom, the homes that were destroyed and rebuilt, the cats who stayed as long as they could and then made way for the new visitor all of them small circles of life that will continue long after he is gone.

But as Uchida says, “Not Yet”. Like Kurosawa himself who feels the light dimming he asks for more time as if playing hide and seek with death whose presence he must eventually acknowledge even if he’s not quite ready to welcome him in. At the last Not Yet Fest that we see times have clearly changed. Uchida’s wife is now present along with the daughters and granddaughters of the students, one of whom points out they’ll soon be genuine old geezers themselves. For a moment we think we see the boy from 1943. Uchida tells the children to find their passion and give their lives to it, imparting one final not quite lesson while gifting them the cake they’ve just brought him in order of his 77th birthday. A 77th birthday is supposed to be lucky, though seven sevens are also 49 which is the length of a Buddhist mourning period and the time it takes to be reborn. The cycle begins again, as Uchida may know as he dreams of childhood hide and seek only to be distracted by a surrealist sky in its pinks and blues, a vista apparently painted by Kurosawa himself who lets the clouds roll into the credits an endless stream of dream and memory on which our lives are mere bubbles that disappear and form anew. But perhaps, not yet.