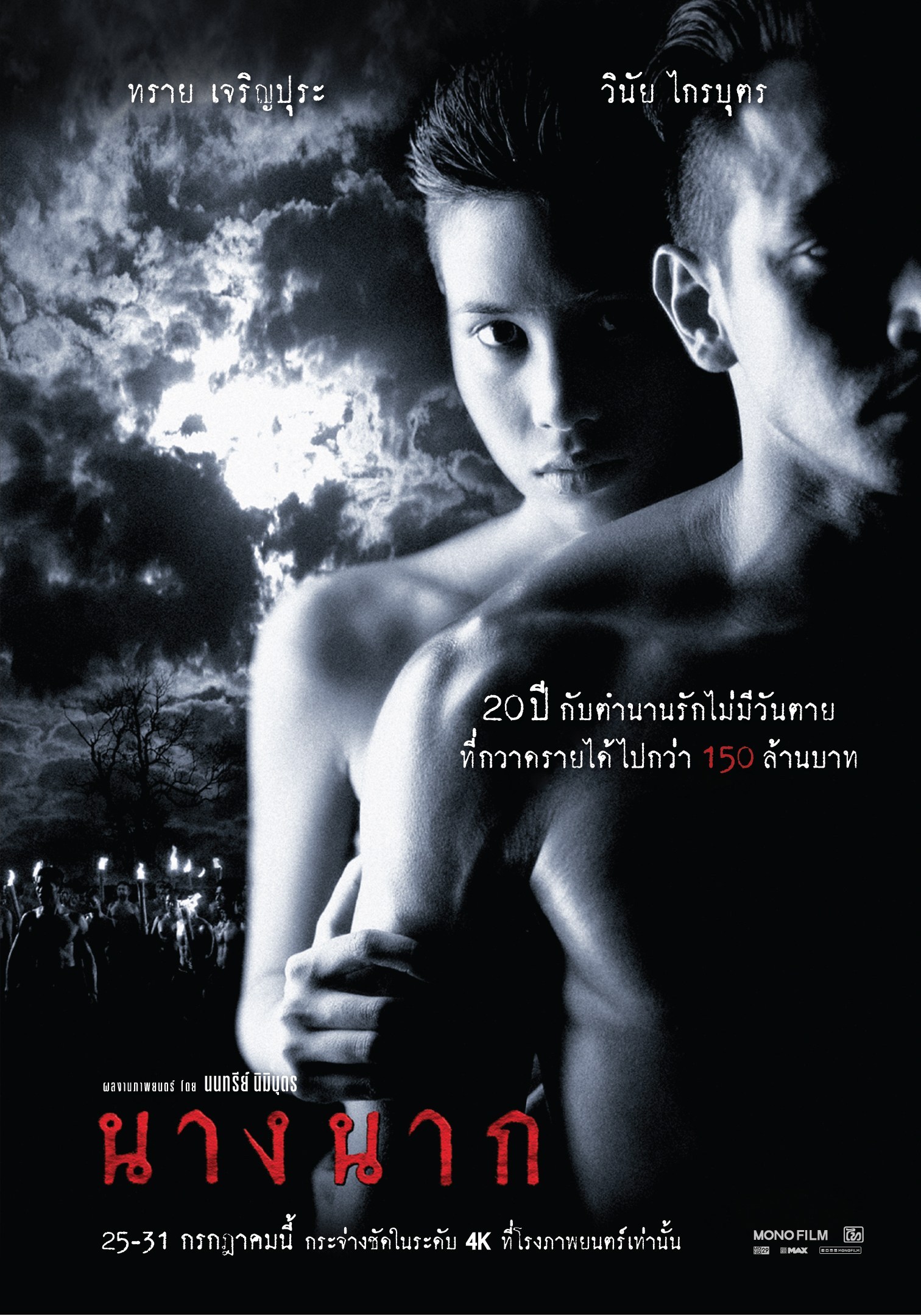

Mae Nak Phra Khanong is one of Thailand’s best known and most enduring ghost stories, though Nonzee Nimibutr’s 1999 adaptation Nang Nak (นางนาก) scales back a little on the inherent terror of the folktale, preferring to focus on the romantic tragedy of a loving couple separated by death. You could then read it as a tale of grief, that the husband returning from war cannot accept his wife is dead, rather than the reverse that the wife’s love and devotion is so strong that it overcomes death itself and becomes something that is in that way terrifying.

It does seem, however, that in this instance the ghost is real and it is vengeful. The wronged wife Nak (Inthira Charoenpura) takes revenge on those who betrayed her from the midwife who stole her wedding ring to a local man who tried to tell her husband, Mak (Winai Kraibutr), that his wife was actually dead. Though the framing of the tale may seem in its way uncomfortably sexist despite its romantic overtones, it’s clear that Nak suffered largely because of the male failure around her. Her husband was conscripted for a war which was really nothing to do with him leaving her, pregnant, to manage their farm alone. The implied cause of the miscarriage which leads to her death in childbirth is overwork and she appears to have received no help from the other villagers with many men apparently remaining in the village. When questioned by Mak, she tells him that the other villagers shunned her and called her an adulteress, disputing the parentage of her child with her husband already away at the war.

But the film does not particularly blame war for Nak’s fate, seemingly accepting it as a necessary duty Mak had to further the cause of his nation which is placed above that he owes to his wife and unborn child. In fact, the ghost issue is later solved only by the intervention of a powerful Buddhist monk, Somdet, which implies that this supranational structure is necessary for maintaining order and that the village is otherwise unable to govern itself. Likewise, it paints Buddhism as a modern religion and essential means of national unity that is inherently superior to the backward superstitions of the villagers who decide to call in a shaman against the advice of the local monk. The shaman turns out to be next to useless and in fact makes things worse until Somdet can arrive and is able to talk peacefully to Nak and convince her that she needs to accept her death and move on to the next cycle of life.

It’s also Somdet who heals Mak of his otherwise fatal war wound and the intercutting of his fight for life with Nak’s during the violence of childbirth suggests that her life is somehow sacrificed for his further emphasising the depth and devotion of her love for him. When his health is recovered, Somdet recommends that Mak become a monk in order to clear out his bad karma but Mak declines explaining that he has a duty to his wife and child in his village and so must return to them. In this way, they become a kind of barrier to his spiritual destiny and emblematic of the attachments he should learn to cast off in order to avoid suffering. Like Nak, Mak’s own devotion extends beyond the grave for he does indeed become a monk and never remarries, keeping the promise to be reincarnated as Nak’s husband in a subsequent life.

The local priest had told Nak that scaring monks is a sin, which is odd in a way that it’s somehow worse to scare these spiritually powerful beings than the ordinary villagers. Nevertheless Nonzee Nimibutr gives her the somewhat familiar attributes of a Thai ghost, allowing her to hang from the ceiling with her hair flowing down while she stares at the monks with bloodshot eyes and a pale face. She is able to enchant Mak so that he does not notice the dilapidation of their home or that all their food is rotten even if he later becomes suspicious of the large number of rats around. Primarily she seems to use natural creatures to enact her revenge with the midwife’s corpse torn apart by lizards, though Mak too has terrifying nightmares of his friend dying in his arms and then melting away with quite sickening effects. Even so, it seems Nonzee Nimibutr is keener to emphasise the romantic tragedy and primacy of Buddhist thought rather than ghostly horror while making it clear that death, along with grief and loss, is something that must be accepted so the spiritual order may be maintained and with it order in the mortal realm.

Trailer (no dialogue)