At the beginning of the 1970s, Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity would put the ninkyo eiga firmly to bed, but in the mid-1960s, they were still his bread and butter. Fukasaku’s earlier career at Toei leant towards the studio’s preference for youthful rebellion but with a stronger trend towards standardised gangster tropes than the countercultural thrills to be found in similar offerings from Nikkatsu. For Fukasaku the rebellion is less cool affectation than it is a necessary revolt against increasing post-war inequality and a constraining society though, as the heroes of If You Were Young, Rage or Blackmail is My Life find out, escape can rarely be found by illicit means. Jiro, the prodigal son of North Sea Dragon (北海の暴れ竜, Hokkai no Abare-Ryu), finds something similar even whilst conforming almost entirely to Toei’s standard “young upstart saves the village” narrative.

At the beginning of the 1970s, Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity would put the ninkyo eiga firmly to bed, but in the mid-1960s, they were still his bread and butter. Fukasaku’s earlier career at Toei leant towards the studio’s preference for youthful rebellion but with a stronger trend towards standardised gangster tropes than the countercultural thrills to be found in similar offerings from Nikkatsu. For Fukasaku the rebellion is less cool affectation than it is a necessary revolt against increasing post-war inequality and a constraining society though, as the heroes of If You Were Young, Rage or Blackmail is My Life find out, escape can rarely be found by illicit means. Jiro, the prodigal son of North Sea Dragon (北海の暴れ竜, Hokkai no Abare-Ryu), finds something similar even whilst conforming almost entirely to Toei’s standard “young upstart saves the village” narrative.

Jiro (Tatsuo Umemiya), dressed in white with jet black sunshades, nonchalantly walks into his childhood fishing village filled with a sense of nostalgia and the expectation of a warm welcome. The village, however, is much changed. There are fewer boats around now, and the fishermen are all ashore. Arriving at his family home he discovers they now live in the boat shed and his mother doesn’t even want to let him in. Jiro, as his outfit implies, has spent his time away as a yakuza, and his family want little to do with him, especially as his father has been murdered by the soulless gangsters who are currently strangling the local fishing industry.

The local fishermen are all proudly tattooed but they aren’t yakuza, unlike the tyrannical son of the local boss, Gen Ashida (Hideo Murota), who carries around a double barrelled shotgun and fearsome sense of authority. The Ashidas have placed a stranglehold around the local harbour, dictating who may fish when and extracting a good deal of the profits. An attempt to bypass them does not go well for Jiro’s mother who is the only one brave enough to speak out against their cruel treatment even if it does her no good.

When Jiro arrives home for unexplained reasons he does so happily, fully expecting to be reunited with his estranged family. Not knowing that his father had died during his absence, Jiro also carries the guilt of never having had the opportunity to explain himself and apologise for the argument that led to him running away. An early, hot headed attempt to take his complaint directly to the Ashidas ends in disaster when he is defeated, bound, and whipped with thick fisherman’s rope but it does perhaps teach him a lesson.

The other boys from the village – Jiro’s younger brother Shinkichi (Hayato Tani) and the brother of his childhood friend Reiko (Eiko Azusa), Toshi (Jiro Okazaki), are just as eager as he is both to avenge the death of Jiro’s father and rid the village of the evil Ashida tyranny. Jiro tries to put them off by the means of a good old fashioned fist fight which shows them how ill equipped they are in comparison with the older, stronger, and more experienced Jiro but their youth makes them bold and impatient. The plot of Toshi and Shinkichi will have disastrous consequences, but also acts as a galvanising force convincing the villagers that the Ashidas have to go.

Jiro takes his natural place as the hero of a Toei gangster film by formulating a plan to undermine the Ashidas’ authority. His major strategic decision is to bide his time but he also disrupts the local economy by attempting to evade the Ashida net through sending the fisherman to other local ports and undercutting the Ashida profit margin. As predicted the Ashidas don’t like it, but cost themselves a crucial ally by ignoring the intense bond between their best fighter and his adorable pet dog. Things do not quite go to plan but just as it looks as if Jiro is about to seal his victory, he stays his sword. The Ashidas’ power is broken and they have lost enough already.

Fukasaku’s approach tallies with the classic narrative as the oppressive forces are ousted by a patient people pushed too far finally deciding to fight back and doing so with strategic intelligence. It is, in one sense, a happy ending but not one without costs as Jiro looks at the restored village with the colourful flags of fishing boats enlivening the harbour and everyone going busily about their work. He knows a sacrifice must be made to solidify his mini revolution and he knows who must make it. Like many a Toei hero before him, he prepares to walk away, no longer welcome in the world his violence has saved but can no longer support.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

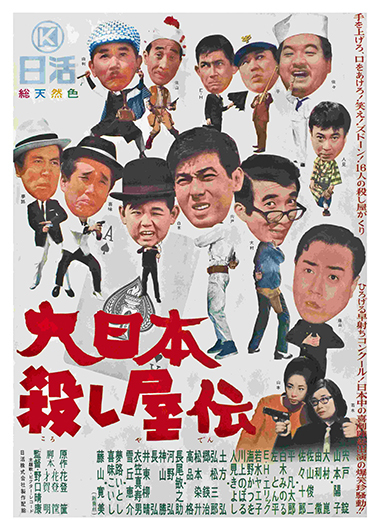

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.

“If you don’t laugh when you see this movie, I’m going to execute you” abacus wielding hitman Komatsu warns us at the beginning of Haryasu Noguchi’s Murder Unincorporated (大日本殺し屋伝, Dai Nihon Koroshiya-den). Luckily for us, it’s unlikely he’ll be forced to perform any “calculations”, and the only risk we currently run is that of accidentally laughing ourselves to death as we witness the absurd slapstick adventures of Japan’s craziest hitman convention when the nation’s “best” (for best read “most unusual”) contract killers descend on a small town looking for “Joe of Spades” – a mysterious assassin known only by the mole on the sole of his foot.