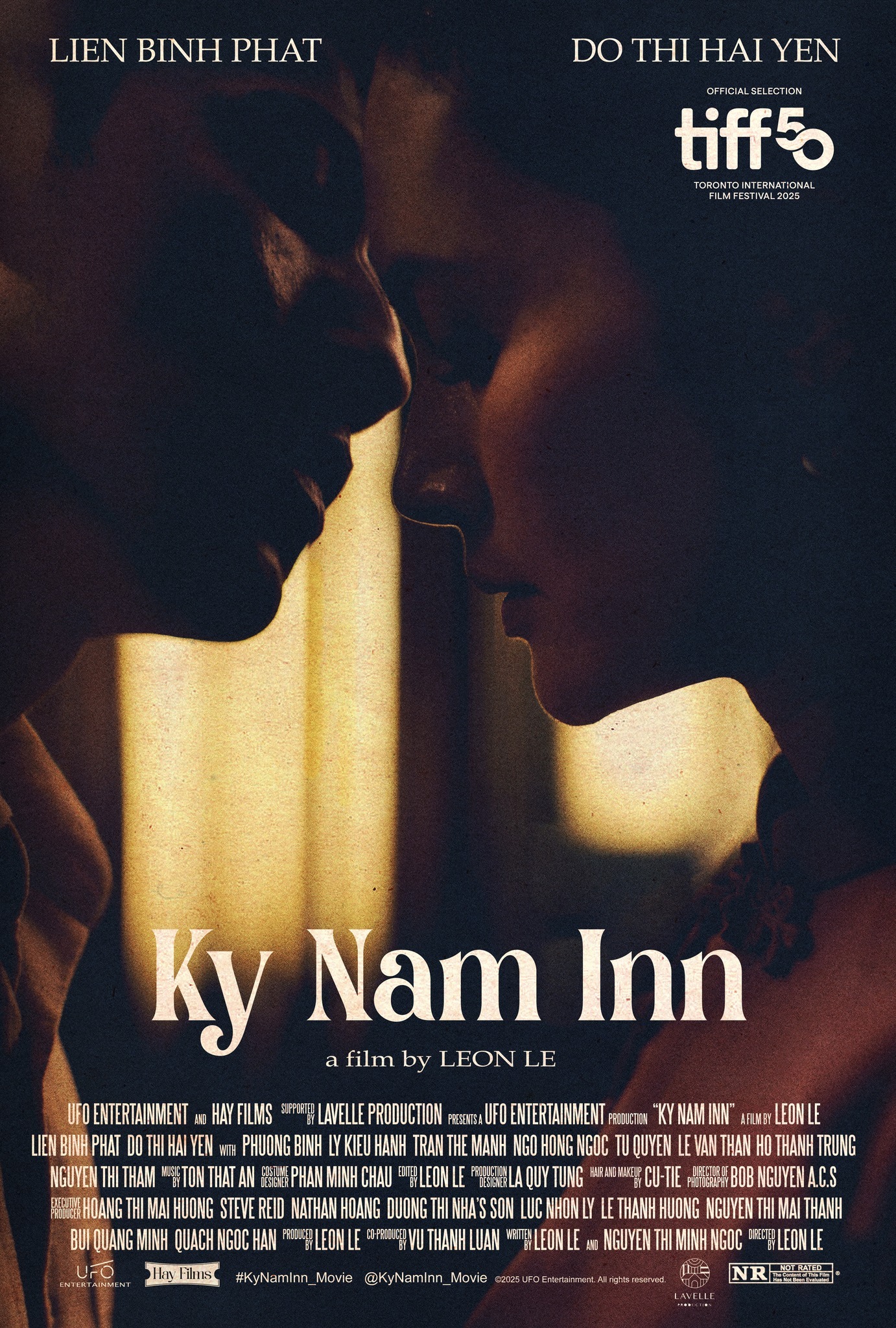

As related in the opening voice over, “ky nam” is a type of agarwood that only forms when the tree is wounded. The tree lets out tiny drops of a fragrant resin to heal itself that in many years become “ky nam”. It also, however, the name of a woman with whom the writer has fallen in love who has herself spent many years trying to heal the past, much as her nation is still doing as it remakes itself after years of war and not to everyone’s liking.

A slow-burning love story, Leon Lê’s Ky Nam Inn (Quán Kỳ Nam) is set mainly in Saigon in 1985 as a “red seed” nephew of an influential Party man is sent to live in a small housing complex while he works on a new translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. The book has been translated before to great acclaim, but the new regime must have a new translation and it must prove as good as the old. Khang (Liên Bỉnh Phát) only became a translator because he was so impressed with the dexterity of Bui Giang’s language in the original translation, but now he must erase and surpass him because times have changed and Bui Giang belongs to the old world. When Khang and Ky Nam encounter him by chance, he’s been reduced to directing street traffic, knocked over by the hustle and bustle of the flower market as if time were flowing past him like a fast-moving current.

In her own way, Ky Nam (Đỗ Thị Hải Yến) is much the same. She was once a well-known writer with a recipe column in a magazine, but is now living a lonely life as a widow running a meal delivery service for her neighbours yet avoided by many of them because of her problematic background. Her husband seems to have died in a labour camp, and her younger son has gone “missing”. 1985 was the year when the highest number of people tried to flee the country. Young men could be conscripted for the war with Cambodia, and so Ky Nam sent her youngest away but there’s been no word of him since. Her surviving son, Don, wants to hold a memorial service believing that the only conclusion is that Duong did not survive the journey though Ky Nam remains confident he’s still out there, somewhere.

Su, a mixed-race boy who helps out in Ky Nam’s kitchen, also wants to leave though in part because he is bullied, discriminated against, and made to feel like a burden by the family who took him in. His uncle refused permission for him to finish high school, and has arranged for him to become a part of another “family” to be able to emigrate to America. As much as he’s there as the new hope of the Communist elite, Khang also has his sights set on studying abroad in France and it’s never clear how long he will be allowed to stay in this transitory space between the new Vietnam and the old which makes his growing affection for Ky Nam all the more poignant. Like him, she is an intellectual well versed in French literature though now finding herself at odds with the contemporary reality. The French schools they attended have all been renamed, as the new regime does its best to erase the history of the colonial era.

Perhaps that’s why Khang is so drawn to her as he struggles with his own role in this society. He barely knew the influential uncle who engineered this future for him and is acutely aware that if his translation’s no good, everyone will say he was only given the opportunity because of his personal connections. Meanwhile, his uncle, Tan, has arranged it so that he won’t be given a key for the front gate and will have to ring the bell to enter the complex while the doorman and community leader will be reporting all his movements. Nevertheless, that doesn’t seem to have much affect on his behaviour as he settles into the community and continues helping Ky Nam even after it’s made clear to him that associating with someone who has a problematic background could negatively affect his standing. As someone says, Khang will eventually have to choose between career and love.

For Ky Nam, it isn’t that much of a choice. She knows this love is impossible, so she tries to refuse Khang’s help and keep him at arms’ length all the while yearning to hold him closer. During their final night together as they roam the streets of Saigon until morning, Ky Nam says she’s reminded of heroine of Camus’ Adulterous Woman who breaks away from her husband to escape to an abandoned fort by herself for a brief taste of freedom before going back to her disappointing life. Khang says he didn’t like the ending, but later wonders if Ky Nam were not like the woman, only pretending to have forgotten her gate key so they could spend this brief time together. He confesses, though, that he doesn’t know how to end his own story and is wary of disrupting the new life that Ky Nam has made for herself after he ironically helped her heal a rift with her judgemental neighbour which has allowed her to expand her business. He now is a kind of exile too, marooned in Hanoi waiting for passage elsewhere having left the apartment complex and along with it his rose to experience more of the world. Yet for all its sadness, there’s a joy in it too that this lost love existed at all and became the tiny drops that may one day save the tree.

Ky Nam Inn screens as part of this year’s San Diego Asian Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)