The Detective Chinatown team head back to turn of the contrary San Francisco in the latest instalment of the mega hit franchise, Detective Chinatown 1900 (唐探1900, Tángtàn 1900). Like many recent mainstream films, its main thrust is that Chinese citizens are only really safe in China, but also implies that diaspora communities exist outside the majority population and therefore can only rely on each other. Nevertheless, there’s something quite uncanny in the film’s ironic prescience as racist politicians wax on about how here rules are made by the people rather than an emperor and plaster “make America strong again” banners on their buses.

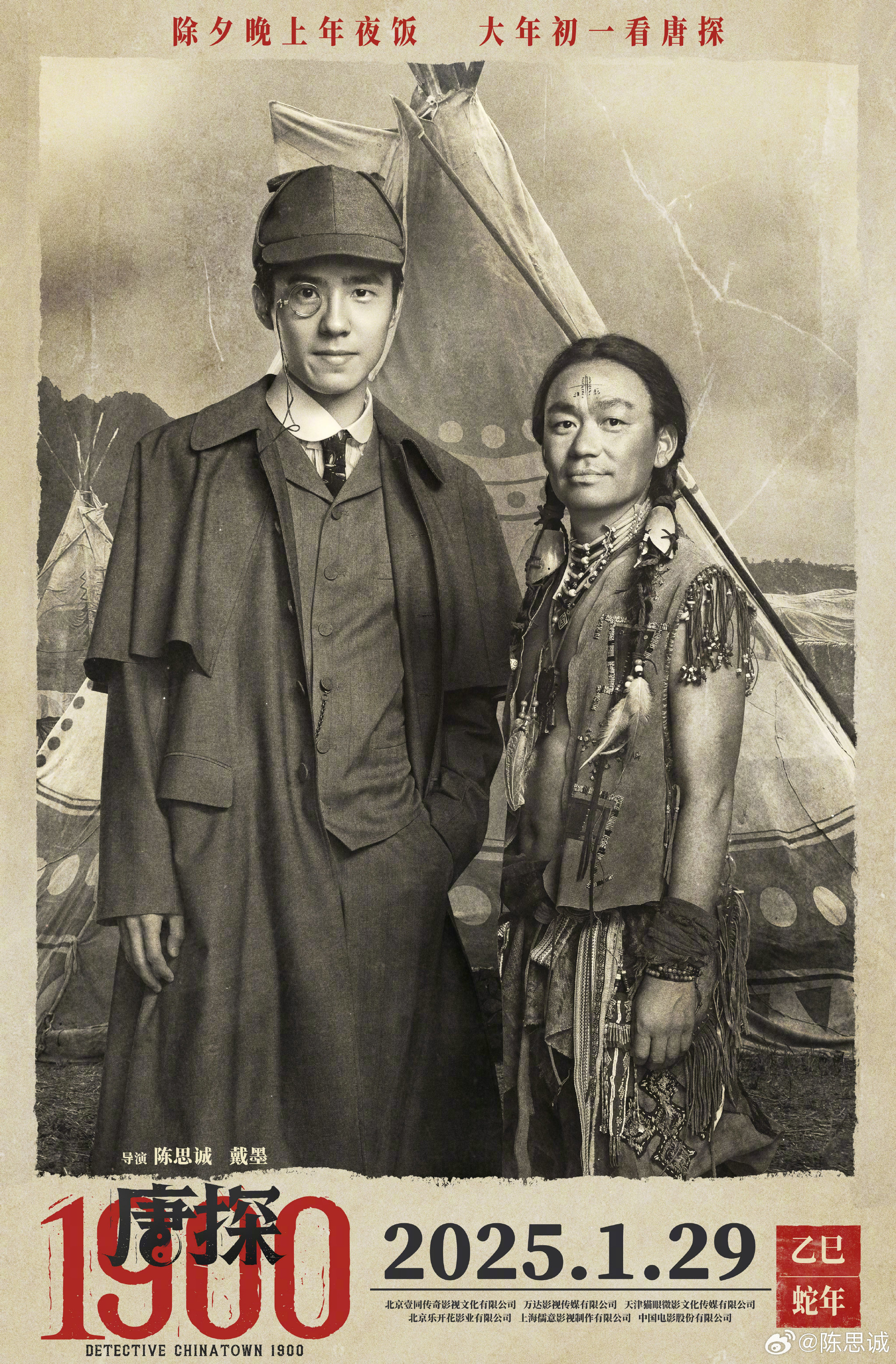

The crime here though is the murder of a young white woman, Alice (Anastasia Shestakova), the daughter of Senator Grant (John Cusack) who is attempting to push the renewal of the Chinese Exclusion Act through government and destroy all the Chinatowns in the United States. An older Native American man was also found dead alongside her. Some have attributed the crime to Jack the Ripper as Alice was mutilated before she died and some of her organs were taken. The son of local gangster Bai (Chow Yun-Fat), Zhenbang (Zhang Xincheng), is quickly arrested for the crime while his father hires Qin Fu (Liu Hairan) to exonerate him believing Qin Fu to be Sherlock Holmes.

What Qin Fu, an expert in Chinese medicine recently working as an interpreter for the famous consulting detective, finds himself mixed up in is also a slow moving revolution as it turns out Zhenbang is involved with the plot to overthrow the Qing dynasty (which would finally fall in 1912). As the film opens, corrupt courtiers to sell off large golden Buddha statues to American “allies” who are later seen saying that they plan to fleece China and then renege on their promises to protect it. Meanwhile, the Dowager Empress has sent emissaries to San Francisco to take out the revolutionaries in hiding there including Sun Yat-sen.

Of course, in this case, the Qing are the bad guys that were eventually overthrown by brave Communist revolutionaries that paved the way for China of today which is alluded to in the closing scenes when Zhenbang’s exiled friend Shiliang (Bai Ke) says that China will one day become the most powerful country in the world implying that no-one will look down on the Chinese people again. But on the other hand, they are still all Chinese and so the emissary tells Qin Fu to “Save China” as he lays dying having met his own end shortly after hearing that the British have invaded Peking signalling the death blow for the Qing dynasty.

Nevertheless, there is a degree of irony in the fact that the secondary antagonist is an Irish gang who have signs reading “no dogs, no Chinese,” mimicking those they themselves famously face. The Irish gang is in league with Grant and content to do his dirty work, while Bai is supported by another prominent man who speaks Mandarin and pretends to be a friend to the Chinese but in reality is against the Exclusion Act on the grounds he wants to go on being able to exploit cheap Chinese labour. In this iteration, Ah Gui (Wang Baoqiang) is “Ghost,” a man whose parents were killed building the American railroad and was subsequently taken in and raised by a Native American community. In Bai’s final confrontation with the authorities, he takes them to task for their hypocrisy reminding them how important the Chinese have been in building the society in which they alone are privileged while “equality” does not appear to extend to them.

Through reinforcing these messages of prejudice and exploitation, the film once again encourages Chinese people living abroad to return home. Though set in 1900, the scenes of protest can’t help but echo those we’ve seen in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic when racist hatred towards Asian communities has become much more open and pronounced. Qin Fu and Ghost do at least succeed in solving the mystery through scientific principles while ironically assisted by an earnest American policeman who says he thinks it’s important to uphold the law even as we can see the head of the golden Buddha sitting behind the victorious politician’s banquet table and realise that in reality taking out Grant has made little difference for the Exclusion Act will still be renewed (it was repealed only in 1943). They may have saved Chinatown, but Bai must sacrifice his American wealth and return to China much the way he left it having reflected on his life in light of the revolutionary course charted by his more earnest son. As Ghost and Qin Fu remark, if things were better there no one would want to come here though they themselves apparently elect to stay, solving more crimes and making sure that their descendants know they were here and where they were from.

International trailer (Simplified Chinese / English subtitles)