The family drama was once the representative genre of Japanese cinema. In the turbulent post-war world, the one unchanging, unbreakable touchstone was the bonds between parents and their children even if it must also be realised that those bonds will necessarily change over time. Tiny cracks might have been visible even in Ozu’s Tokyo Story in the growing disconnection between the old folks in the country and their city kids, but it wasn’t until the ‘80s when Japan’s economic recovery had fully taken hold that the family itself began to come under fire. Yoshimitu Morita’s The Family Game kickstarted a trend of family implosion movies which implied that familial bonds were more social affectation than genuine connection, but post-bubble the tables turned again. These days, Hirokazu Koreeda has picked up the family drama mantle, depicting broadly positive pictures of normal family life. It is then all the stranger that his protege, Miwa Nishikawa, should be the one to ask again if family really is all it’s cracked up to be.

An ordinary breakfast in the Akechi household. Grandpa (Matsunosuke Shofukutei ) is dipping his toast in the coffee again while salaryman dad Yoshiro (Sei Hiraizumi) reads his paper. Schoolteacher Tomoko (Miho Tsumiki) barely has time to look at her breakfast before her mother, Akiko (Naoko Otani), reminds her that today is “Wednesday” – not only does she need her PE kit, but it’s also the day that her fiancé, Kamata (Toru Tezuka), is coming round to tea to meet the folks. The atmosphere is pleasant, genial, but why has Yoshiro had his mobile phone cut off and is the bald spot Akiko has just discovered on the top of her head really anything to worry about?

The Akechis are the archetype of a modern middle-class family, living a comfortable life in a nice home while dad goes out to work and mum does everything else. It is not, however, quite as it seems. Yoshiro’s phone has been cut off because he hasn’t paid the bill. He hasn’t paid the bill because he’s lost his job. He hasn’t told his wife he’s lost his job because he’s too ashamed, so he’s taken out vast loans from gangsters rather than trying to find a more honest solution. Mum Akiko plays the dutiful housewife, cooking, cleaning, putting up with Yoshiro’s imperious behaviour and looking after grandpa who has advanced dementia and thinks he’s still at war. In reality she’s bored and resentful, tired of the burden of looking after her husband’s ungrateful father and longing to have some time for herself. The only uncorrupted member of the family is schoolteacher Tomoko who finds herself giving a strange lesson on the evils of lying to her class of small children. Tomoko is perhaps too uncorrupted, prim as a schoolmarm but dull with it.

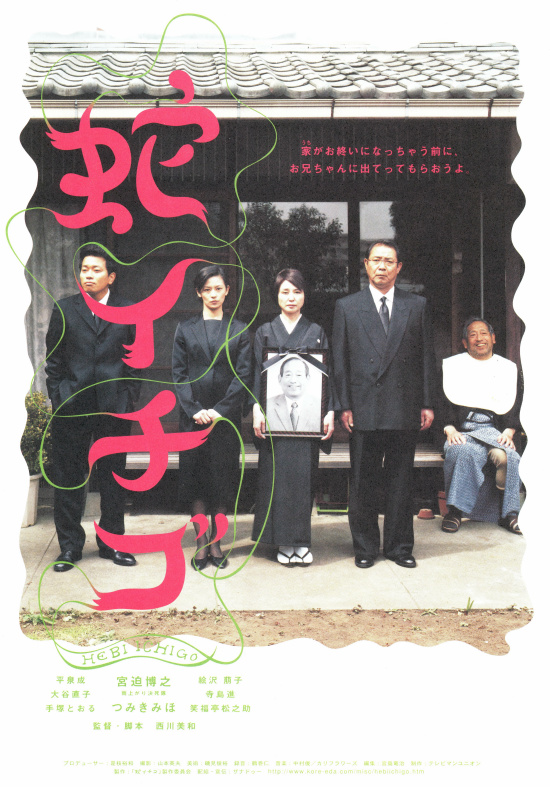

When grandpa meets an unfortunate end, the longstanding family secret is revealed – Tomoko is not an only child, she had an older brother, Shuji (Hiroyuki Miyasako), who had been expelled from the family for his immoral ways – i.e, lying, cheating, and stealing. In fact, Shuji’s return was an accident – his main job is stealing the condolence money from funerals and he just happened to be at the one next door. Shuji’s conman credentials might be just what the family needs, but could they and should they let him save them and is “saving” the family that rejected him really a part of Shuji’s grand plan?

Japan’s rapid economic recovery is usually blamed for the collapse of the family, sending sons away from the villages and prizing the commercial over the spiritual. Tomoko’s fiance, Kamata, has a slightly different take on the problem. After his first meal with the Akechis he’s touched by the warm and friendly family atmosphere, comparing them favourably with his own upperclass family which he feels to be cold and austere. The class difference and Kamata’s obvious discomfort surrounding it is one problem as is his problematic characterisation of Tomoko’s family as earnest and hardworking as, perhaps, he thinks people without inherited wealth ought to be is another, but the real irony is reserved for Kamata’s eventual reaction to discovering the truth. Yoshiro didn’t take to Kamata because he thought him “unconventional” with his unkempt hair and pretentious tastes, but Kamata proves himself the most conventional of all in his cruel rejection of his fiancée over what he sees as a betrayal by her family.

Wild berries, once they take root, quickly take over, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. Secrets, and the need to keep them, have eaten away at the foundations of the Akechi family but which is the best way to repair them – starting all over again and working hard to put things right, as Tomoko would have it, or opting for Shuji’s dishonest quick fix? The youngsters battle it out amongst themselves for the soul of the family unit while mum and dad are just too world weary to even care anymore. Faith in the family may be running at an all time low, but Nishikawa at least manages to mine the situation for all of its bleak irony, laughing along knowingly with each dark revelation or small tragedy.

Screened as part of Archipelago: Exploring the Landscape of Contemporary Japanese Women Filmmakers.

Original trailer (no subtitles)