A minor controversy erupted in Japan in 2019 when then finance minister Taso Aso issued a statement recommending that couples should have 20 million yen (£104,620 total at the time of writing) saved for their retirement on top of the state pension in order to live a comfortable life in old age. All things considered, 20 million yen actually sounds like quite a low sum for two people who might live another 30 years post-employment. Nevertheless, Atsuko (Yuki Amami) and her husband Akira (Yutaka Matsushige) are now in their mid-50s and don’t have anywhere near that amount in savings. They’re still paying off their mortgage and though their children are grown-up, neither of them seem to be completely independent financially and both still live at home.

Tetsu Maeda’s familial comedy What Happened to Our Nest Egg!? (老後の資金がありません!, Rogo no shikin ga arimasen!) explores the plight of the sandwich generation which finds itself having to support elderly relatives while themselves approaching retirement and still needing to support their children who otherwise can’t move forward with their lives. Seeing an accusatory ad which seems to remind her personally that even 20 million yen isn’t really enough when you take into consideration the potential costs of medical treatment or a place in a retirement home, Atsuko has a sudden moment of panic over their precarious financial situation. The apparently sudden death of Akira’s 90-year-old father acts as a sharp wake up call especially as Akira’s apparently very wealthy but also selfish and materialistic sister Shizuko (Mayumi Wakamura) bamboozles him into paying for the entirety of the funeral while pointing out that they’ve been footing most of the bill for the parents’ upkeep over the last few years.

There was probably a better time to discuss the financial arrangements than with their father on his deathbed in the next room, but in any case Shizuko doesn’t pay attention to Atsuko’s attempt to point out they’ve been chipping in too. Akira’s mother Yoshino (Mitsuko Kusabue) also reminds them that their family was once of some standing and a lot of people will be attending the funeral so they need to make sure everything is done properly. The funeral arranger is very good at her job and quickly guilts Atsuko into spending large sums of money on pointless funeral pomp to avoid causing offence only to go to waste when hardly anyone comes because, as she later realises, all of the couple’s friends have already passed away, are bedridden, or too ill to travel.

Yoshino is however in good health. When Shizuko suddenly demands even more money for her upkeep, Atsuko suggests Yoshino come live with them but it appears that she has very expensive tastes that don’t quite gel with their ordinary, lower-middle class lifestyle. Having lived a fairly privileged life and never needing to manage her finances, Yoshino has no idea of the relative value of money and is given to pointless extravagance that threatens to reduce Atsuko’s dwindling savings even more while in a moment of cosmic irony both she and Akira are let go from their jobs. Now they’re in middle age, finding new ones is almost impossible while their daughter suddenly drops the bombshell that she’s pregnant and is marrying her incredibly polite punk rocker boyfriend whose parents run a successful potsticker restaurant and are set on an elaborate wedding.

The film seems to suggest that Atsuko and Akira can’t really win. They aren’t extravagant people and it just wasn’t possible for them to have saved more than they did nor is it possible for them to save more in the future. Instead it seems to imply that what they should do is change their focus and the image they had of themselves in their old age. One of the new colleagues that Akira meets in a construction job has moved into a commune that’s part of the radical new housing solution invented by his old friend Tenma (Sho Aiwaka). Rather than building up a savings pot, the couple decide to reduce their expenses by moving into a share house and living as part of a community in which people can support each other by providing child care and growing their own veg. Yoshino too comes to an appreciation of the value of community and the new exciting life that she’s experienced since moving in with Atsuko. It may all seem a little too utopian, but there is something refreshing in the suggestion that what’s needed isn’t more money but simply a greater willingness to share, not only one’s physical resources but the emotional ones too in a society in which everyone is ready to help each other rather than competing to fill their own pots as quickly as possible.

What Happened to Our Nest Egg!? screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (English subtitles)

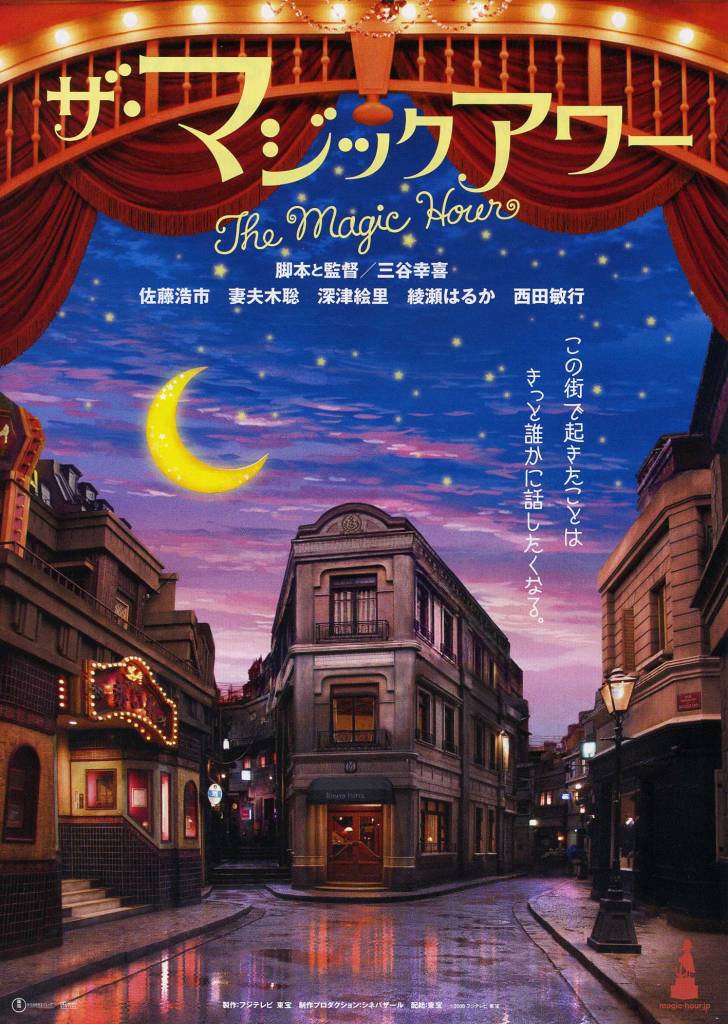

If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.

If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.