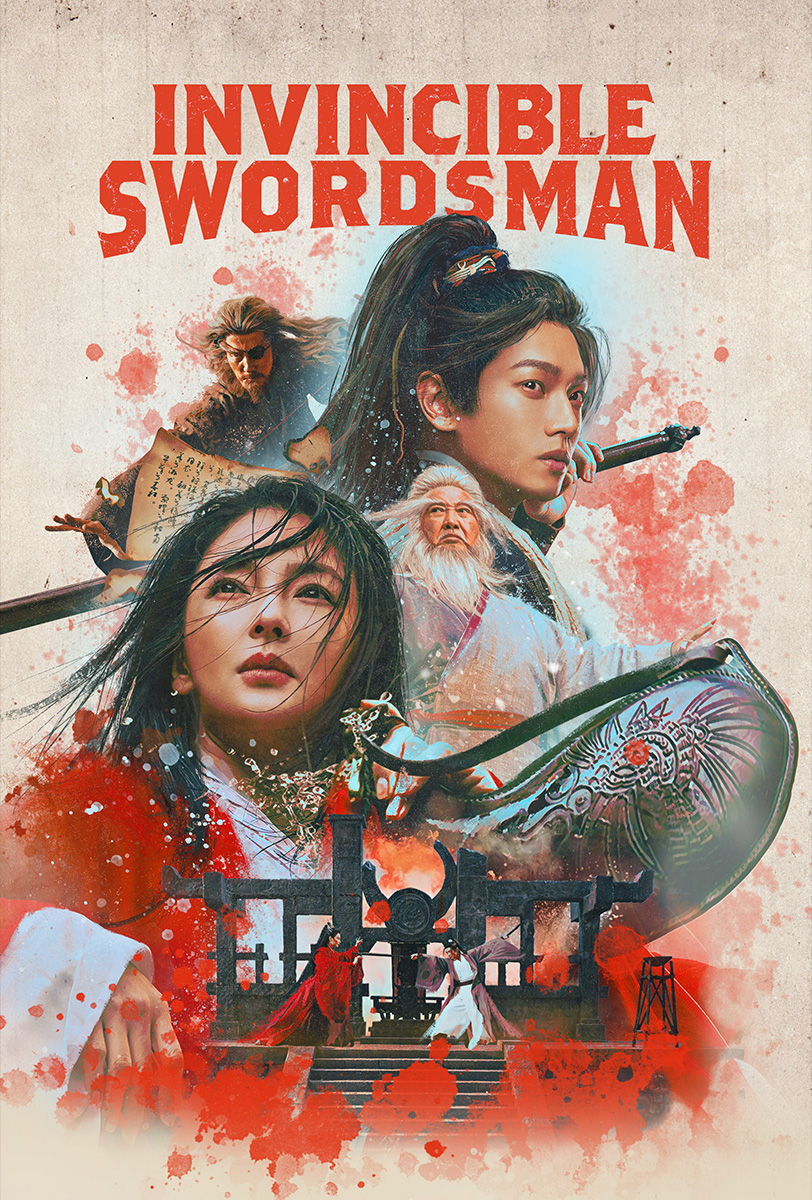

Picking up where the previous film left off, Yin Jiao (Chen Muchi) has been taken to the immortal realm of Kunlun where they first assume it’s too late to save him what with his head and his body having become separated. But on a closer look, the Immortals realise that the sheer force of Yin Jiao’s resentment has sustained him. They can save him after all, but when they try, he usurps all their power and becomes something that not even they can control. The future of the Shang, in fact of China itself, now rests with him. Will he be able to contain his rage and fight for a better world, or will it get the better of him and he’ll burn it all to hell in revenge?

To that extent, the second part in the Creation of the Gods trilogy inspired by the classic foundation myth The Investiture of the Gods, presents a similar problem to the first. Given the opportunity to save the world or enrich oneself, what will most people choose? Yin Shou chose the latter and is still in thrall to his fox demon lover who is now herself in mortal peril having transferred Yin Shou’s wounds to herself to heal him to the extent that her own body, that of rebellious lord Su Hu’s daughter Daj (Narana Erdyneeva), has begun to decay.

There is something quite tragic and poignant about the almost romance that arises between Ji Fa and Deng Chanyu who bond over the realisation that they are really fighting for the same thing, family, even he fights for the living and she the dead. During her time in Xiqi, Deng Chenyu gains a glimpse of another life in which she might find the home she’s been searching for only to realise that she must sacrifice herself for its survival though in doing so she might also achieve her dream of dying on the battlefield with her family. As the people of Xiqi hold a celebration for Yin Jiao’s return, two old ladies grab Jiang Ziya (Huang Bo) and try to pull him into a reel. He protests he has more important matters to deal with, but as the old ladies remind him happiness is the most important matter. In effect, that’s what each of them is fighting for in opposing the by now quite literally lifeless tyranny that Yin Shou represents. His romance with the fox demon has its poignancy too in her apparent willingness to sacrifice herself for him and resultant powerlessness to save herself while he can only rely on the might of giants and demonic magic in order to cement his rule.

Accelerating the pace, Wuershan moves from set piece to set piece beginning with an epic horse chase along a narrow mountain road as Ji Fa and Den Chanyu (Nashi) face off against each other while building progressively towards the assault in Xiqi and confrontation with end boss Wen Zhong (Wu Hsing-kuo). The influence of the supernatural only grows in strangeness as Wen Zhong uses his third eye to create deadly beams of light that paralyse all caught in their beams to make his soldiers’ jobs that much easier as they wipe out Xiqi. Demonic magician Shen Gongbao (Xia Yu) lurks in the background preparing a huge zombie army with his “Deathworms” spell and continuing to disconcertingly float about as a severed head. This time around, altruism squarely defeated selfishness, but who knows if the world will be as lucky next time?

Trailer (English / Simplified Chinese subtitles)