Despite its rich dramatic seam, the fate of the lonely, long serving Japanese office lady approaching the end of the career she either sacrificed everything for or ended up with by default has mostly been relegated to a melancholy subplot – usually placing her as the unrequited love interest of her oblivious soon to be retiring bachelor/widower boss. Daihachi Yoshida’s Pale Moon was perhaps the best recent attempt to bring this story centre stage in its neat contrasting of the loyal employee about to be forcibly retired by her unforgiving bosses and the slightly younger woman who decides she’ll have her freedom even if she has to do something crazy to get it, but Atsuko Hirayanagi’s Oh Lucy! (オー・ルーシー!) is a more straightforward tale of living with disappointment and temporarily deluding oneself into thinking there might be an easier way out than simply facing yourself head on.

Despite its rich dramatic seam, the fate of the lonely, long serving Japanese office lady approaching the end of the career she either sacrificed everything for or ended up with by default has mostly been relegated to a melancholy subplot – usually placing her as the unrequited love interest of her oblivious soon to be retiring bachelor/widower boss. Daihachi Yoshida’s Pale Moon was perhaps the best recent attempt to bring this story centre stage in its neat contrasting of the loyal employee about to be forcibly retired by her unforgiving bosses and the slightly younger woman who decides she’ll have her freedom even if she has to do something crazy to get it, but Atsuko Hirayanagi’s Oh Lucy! (オー・ルーシー!) is a more straightforward tale of living with disappointment and temporarily deluding oneself into thinking there might be an easier way out than simply facing yourself head on.

Middle-aged office lady Setsuko (Shinobu Terajima) is the office old bag. Unpopular, she keeps herself aloof from her colleagues, refusing the sweets a lovely older lady (herself somewhat unpopular but for the opposite reasons) regularly brings into the office, and bailing on after hours get togethers. Her life changes one day when the man behind her on a crowded station platform grabs Setsuko’s chest and says goodbye before hurling himself in front of the train. Such is life.

Taking some time off work she gets a call from her niece, Mika (Shioli Kutsuna) to meet her in the dodgy maid cafe in which she has been working. Mika has a proposition for her – having recently signed up for a year’s worth of non-refundable English classes, Mika would rather do something else with the money and wonders if she could “transfer” the remainder onto Setsuko. Despite her tough exterior Setsuko is something of a soft touch and agrees but is surprised to find the “English School” seems to be located in room 301 of a very specific brothel. John (Josh Hartnett), her new teacher, who has a strict English only policy, begins by giving Setsuko a large hug before issuing her a blonde wig and rechristening her “Lucy”. Through her English lesson, “Lucy” also meets another man in the same position “Tom” (Koji Yakusho) – a recently widowed, retired detective now working as a security consultant. Setsuko is quite taken with her strange new hobby, and is heartbroken to realise Mika and John are an item and they’ve both run off to America.

Setsuko’s journey takes her all the way to LA with her sister, Ayako (Kaho Minami), desperate to sort her wayward daughter out once and for all. As different as they are, Ayako and Setsuko share something of the same spikiness though Setsuko’s cruel streak is one she deeply regrets and only allows out in moments of extreme desperation whereas a prim sort of bossiness appears to be Ayako’s default. Setsuko’s Tokyo life is one of embittered repression, having been disappointed in love she keeps herself isolated, afraid of new connections and contemptuous of her colleagues with their superficial attitudes and insincere commitment to interoffice politeness. Suicide haunts her from that first train station shocker to the all too common “delays caused by an incident on the line” and the sudden impulsive decision caused by unkind words offered at the wrong moment.

“Lucy” the “relaxed” American blonde releases Setsuko’s better nature which had been only glimpsed in her softhearted agreeing to Mika’s proposal and decision to allow Ayako to share her foreign adventure. John’s hug kickstarted something of an addiction, a yearning for connection seemingly severed in Setsuko’s formative years but if “Lucy” sees John as a symbol of American freedoms – big, open, filled with possibilities, his homeland persona turns out to be a disappointment. Just like the maid’s outfit Setsuko finds in John’s wardrobe, John’s smartly bespectacled English teacher is just a persona adopted in a foreign land designed to part fools from their money. Still, Setsuko cannot let her delusion die and continues to see him as something of a saviour, enjoying her American adventure with girlish glee until it all gets a bit a nasty, desperate, and ultimately humiliating.

Having believed herself to have only two paths to the future – being “retired” like the office grandma, pitied by the younger women who swear they’ll never end up like her (much as Setsuko might have herself), or making a swift exit from a world which has no place for older single women, Setsuko thought she’d found a way out only to have all of her illusions shattered all at once. “Lucy” showed her who she really was, and it wasn’t very pretty. Still, even at this late stage Setsuko can appreciate the irony of her situation. That first hug that seemed so forced and awkward, an insincere barrier to true connection, suddenly finds its rightful destination and it looks like Setsuko’s train may finally have come in.

Screened at Raindance 2017

Expanded from Atsuko Hirayanagi’s 2014 short which starred Kaori Momoi.

Clip (English subtitles)

As usual

As usual  Of course there’s plenty of blockbuster fare on offer too from the latest in the Death Note franchise to cat-centric dramas, tales of Shogi playing geniuses, splatter horror, and one family’s strange journey to familial harmony when all the lights go off.

Of course there’s plenty of blockbuster fare on offer too from the latest in the Death Note franchise to cat-centric dramas, tales of Shogi playing geniuses, splatter horror, and one family’s strange journey to familial harmony when all the lights go off. Alongside latest releases,

Alongside latest releases,  Documentary fans also have a lot to look forward to with three very different explorations of modern Japanese life.

Documentary fans also have a lot to look forward to with three very different explorations of modern Japanese life. There’s no shortage of animation either with four new releases including the award winning In this Corner of the World, and Studio Ghibli classic Princess Mononoke.

There’s no shortage of animation either with four new releases including the award winning In this Corner of the World, and Studio Ghibli classic Princess Mononoke. Trippy psychedelic road movie,

Trippy psychedelic road movie,

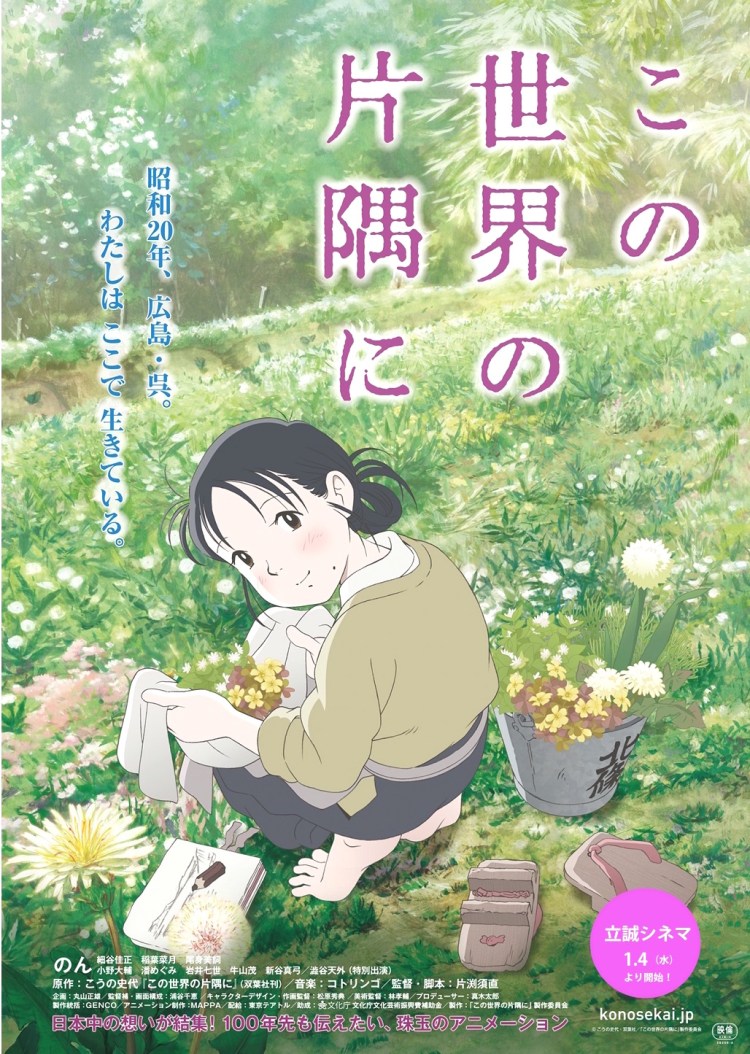

Depictions of wartime and the privation of the immediate post-war period in Japanese cinema run the gamut from kind hearted people helping each other through straitened times, to tales of amorality and despair as black-marketeers and unscrupulous crooks take advantage of the vulnerable and the desperate. In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に, Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), adapted from the manga by Hiroshima native Fumiyo Kouno, is very much of the former variety as its dreamy, fantasy-prone heroine is dragged into a very real nightmare with the frontier drawing ever closer and the threat of death from the skies ever more present but manages to preserve something of herself even in such difficult times.

Depictions of wartime and the privation of the immediate post-war period in Japanese cinema run the gamut from kind hearted people helping each other through straitened times, to tales of amorality and despair as black-marketeers and unscrupulous crooks take advantage of the vulnerable and the desperate. In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に, Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), adapted from the manga by Hiroshima native Fumiyo Kouno, is very much of the former variety as its dreamy, fantasy-prone heroine is dragged into a very real nightmare with the frontier drawing ever closer and the threat of death from the skies ever more present but manages to preserve something of herself even in such difficult times.

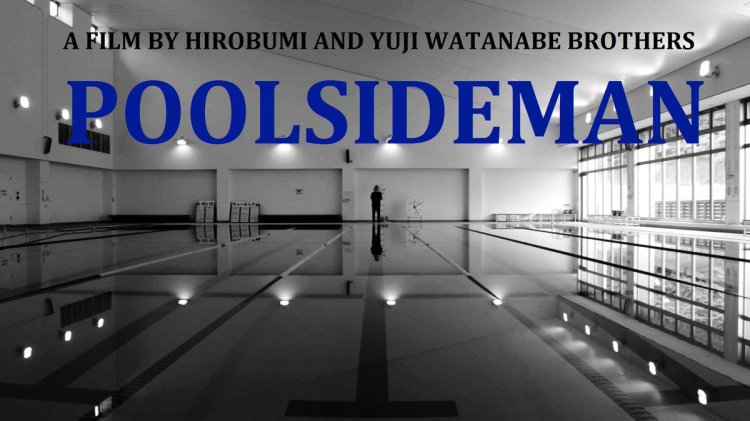

Around halfway through Poolsideman (プールサイドマン), the director himself playing an overly chatty colleague of the film’s protagonist, embarks on a lengthy rant about encroaching middle-age which is instantly relatable to those who find themselves at a similar juncture. He’s sure the world seemed better when he was a child, there wasn’t all of this distress and anxiety – everything just seemed like it would go on forever but time has inexplicably sped up with a series of rapid changes packed into recent years. The life of a poolsideman is improbably intense, or at least it is for Mizuhara (Gaku Imamura) whose days are all the same but filled with tension and the low simmer of something waiting to explode. Loosely inspired by the real life case of a man who left Japan for the Middle East with the idea of joining Isis, Poolsideman wants to explore why such a surreal thing might happen but finds it all too plausible.

Around halfway through Poolsideman (プールサイドマン), the director himself playing an overly chatty colleague of the film’s protagonist, embarks on a lengthy rant about encroaching middle-age which is instantly relatable to those who find themselves at a similar juncture. He’s sure the world seemed better when he was a child, there wasn’t all of this distress and anxiety – everything just seemed like it would go on forever but time has inexplicably sped up with a series of rapid changes packed into recent years. The life of a poolsideman is improbably intense, or at least it is for Mizuhara (Gaku Imamura) whose days are all the same but filled with tension and the low simmer of something waiting to explode. Loosely inspired by the real life case of a man who left Japan for the Middle East with the idea of joining Isis, Poolsideman wants to explore why such a surreal thing might happen but finds it all too plausible.

Tsugumi Ohba and Takashi Obata’s Death Note manga has already spawned three live action films, an acclaimed TV anime, live action TV drama, musical, and various other forms of media becoming a worldwide phenomenon in the process. A return to cinema screens was therefore inevitable – Death Note: Light up the NEW World (デスノート Light up the NEW World) positions itself as the first in a possible new strand of the ongoing franchise, casting its net wider to embrace a new, global world. Directed by Shinsuke Sato – one of the foremost blockbuster directors in Japan responsible for Gantz,

Tsugumi Ohba and Takashi Obata’s Death Note manga has already spawned three live action films, an acclaimed TV anime, live action TV drama, musical, and various other forms of media becoming a worldwide phenomenon in the process. A return to cinema screens was therefore inevitable – Death Note: Light up the NEW World (デスノート Light up the NEW World) positions itself as the first in a possible new strand of the ongoing franchise, casting its net wider to embrace a new, global world. Directed by Shinsuke Sato – one of the foremost blockbuster directors in Japan responsible for Gantz,

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

When tragedy strikes the one thing you ought to be able to rely on is your family, but when the tragedy occurs within that sacred space which exits between you what is to be done? Yosuke Takeuchi’s The Sower (種をまく人, Tane wo Maku Hito) attempts to provide an answer whilst putting one very ordinary, loving and forgiving family through a series of tests and tragedies. Lies, regret, and despair conspire to ruin the lives of four once happy people but even in the midst of such a shocking, unexpected event there is still time to turn towards the sun rather than continuing in the darkness.

When tragedy strikes the one thing you ought to be able to rely on is your family, but when the tragedy occurs within that sacred space which exits between you what is to be done? Yosuke Takeuchi’s The Sower (種をまく人, Tane wo Maku Hito) attempts to provide an answer whilst putting one very ordinary, loving and forgiving family through a series of tests and tragedies. Lies, regret, and despair conspire to ruin the lives of four once happy people but even in the midst of such a shocking, unexpected event there is still time to turn towards the sun rather than continuing in the darkness. Self disgust is self obsession as the old adage goes. It certainly seems to ring true for the “hero” of Miwa Nishikawa’s latest feature, The Long Excuse (永い言い訳, Nagai Iiwake) , in which she adapts her own Naoki Prize nominated novel. In part inspired by the devastating earthquake which struck Japan in March 2011, The Long Excuse is a tale of grief deferred but also one of redemption and self recognition as this same refusal to grieve forces a self-centred novelist to remember that other people also exist in the world and have their own lives, emotions, and broken futures to dwell on.

Self disgust is self obsession as the old adage goes. It certainly seems to ring true for the “hero” of Miwa Nishikawa’s latest feature, The Long Excuse (永い言い訳, Nagai Iiwake) , in which she adapts her own Naoki Prize nominated novel. In part inspired by the devastating earthquake which struck Japan in March 2011, The Long Excuse is a tale of grief deferred but also one of redemption and self recognition as this same refusal to grieve forces a self-centred novelist to remember that other people also exist in the world and have their own lives, emotions, and broken futures to dwell on.