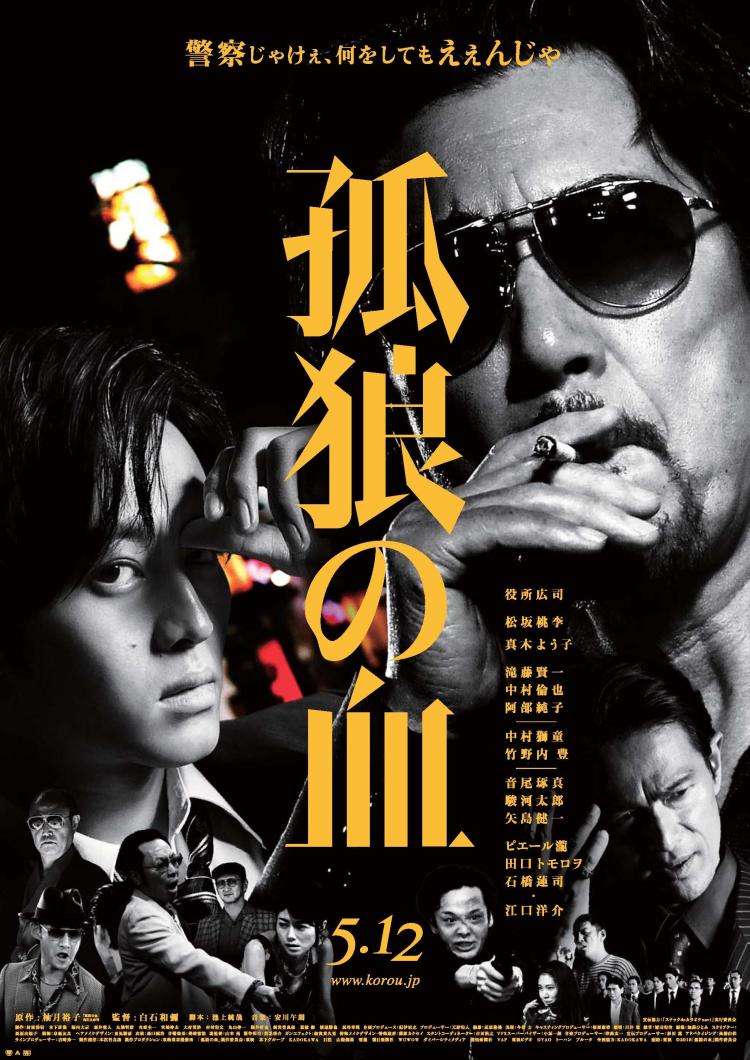

Though Japanese cinema is no stranger to noir, the genre has perhaps failed to gain the foothold it occupies in overseas. Nevertheless, noir is where Norichika Oba aims to take us in his second feature as an ex-con emerges from prison with only one thing on his mind – revenge. The poetically titled Cyclops (キュクロプス) is heady noir filled with unreliable narratives, not least that coming from our foggy headed protagonist, in which the sands of truth are constantly shifting beneath our feet. Then again, perhaps the truth is better off buried. Clarity delivers its own burdens.

Though Japanese cinema is no stranger to noir, the genre has perhaps failed to gain the foothold it occupies in overseas. Nevertheless, noir is where Norichika Oba aims to take us in his second feature as an ex-con emerges from prison with only one thing on his mind – revenge. The poetically titled Cyclops (キュクロプス) is heady noir filled with unreliable narratives, not least that coming from our foggy headed protagonist, in which the sands of truth are constantly shifting beneath our feet. Then again, perhaps the truth is better off buried. Clarity delivers its own burdens.

14 years ago Shinohara (Mansaku Ikeuchi) went to prison for the murder of his wife, Akiko (Ako). He was discovered cradling her lifeless body in a hotel room covered in blood next to the body of another man – Tezuka, a politician, thought to be her lover. After his business went under Shinohara started to drink, heavily. At the time of the incident he was an alcoholic and claims to have no memory of anything prior to discovering his wife’s body owing to being in a state of permanent inebriation. He is sure, however, that he would never have hurt her and denies all the charges. Nevertheless, he’s spent the last 14 years in custody keeping his head down and is about to be paroled. Which is where Matsuo (Kouzou Satou) comes in. A sergeant on the original case, Matsuo has long been harbouring feelings of guilt over the way the affair was handled and claims to have discovered the identity of the “real” killer – a petty yakuza called Zaizen (Hikohiko Sugiyama) who was after the politician and offed Akiko to tie up loose ends. The law can no longer help in this case, but Matsuo suggests Shinohara pursue his own justice and put an end to the matter in the old fashioned way.

What ensues is a complicated cat and mouse game as Shinohara, a bruiser with a prison education in street violence, prepares to take on a vicious and vindictive mob boss who he believes took his wife’s life on a whim to further his own career. Matsuo teams him up with one of Zaizen’s guys, Nishi (Yu Saito), who supposedly wants to do “the right thing” in training a rookie to take out his boss. Meanwhile, Shinohara has also gotten himself into trouble by visiting a local bar named Galatea which is run by a mama-san who looks exactly like Akiko and is also under threat from Zaizen and his collection of sleazy henchmen.

Of course, nothing is quite as it seems and Shinohara, perhaps naively trusting almost everyone he comes into contact with, is left with no clear indication of who he should believe and which story is likely to be the most “true”. Lying back on a jetty under the pale white moon, he thinks he sees the image of his wife, ghostly yet dressed in a fiery red which reflects back on him, bathing his face. Shinohara has a series of nightmares or perhaps flashbacks in which he relives the murder, seeing the killer remove his balaclava but imagining a different face every time.

The title of the film comes from a painting in the bar which is inspired by Greek mythology and features a scene of the giant cyclops Polyphemus hovering behind a mountain while his unrequited object of affection, Galatea, hides herself below. Haru (Ako), the bar’s mama-san, aligns herself with Galatea as a woman trapped between conflicting emotions and effectively held prisoner by her own inertia, longing for escape but unwilling to accept it. Shinohara, at this point sporting an eyepatch and likened to the quasi-stalker giant, wonders if the cyclops has in some way forgotten what it was he was looking in the first place and is simply wandering without aim or purpose. Shinohara has indeed forgotten many things, holding the key to his own salvation all along but proving slow to realise the extent to which he is being misused.

Yet for all his talk of vengeance, Shinohara remains a good and kind man who wants to protect the innocent even while punishing the guilty. Adopting a stray dog, perhaps out of identification with its lonely existence, Shinohara’s humanity begins to resurface enabling him to form an oddly genuine friendship with Nishi even whilst suspecting that he is not all he seems. The bad guys get what’s coming them, but it’s forgiveness that eventually saves the day as the two men find a kind of brotherhood born of mutual understanding and respect. Freedom is won and then given away freely as the cyclops regains his sight, learning to look within for the key to all mysteries while walking a dark and dangerous path towards salvation.

Screened at Nippon Connection 2018.