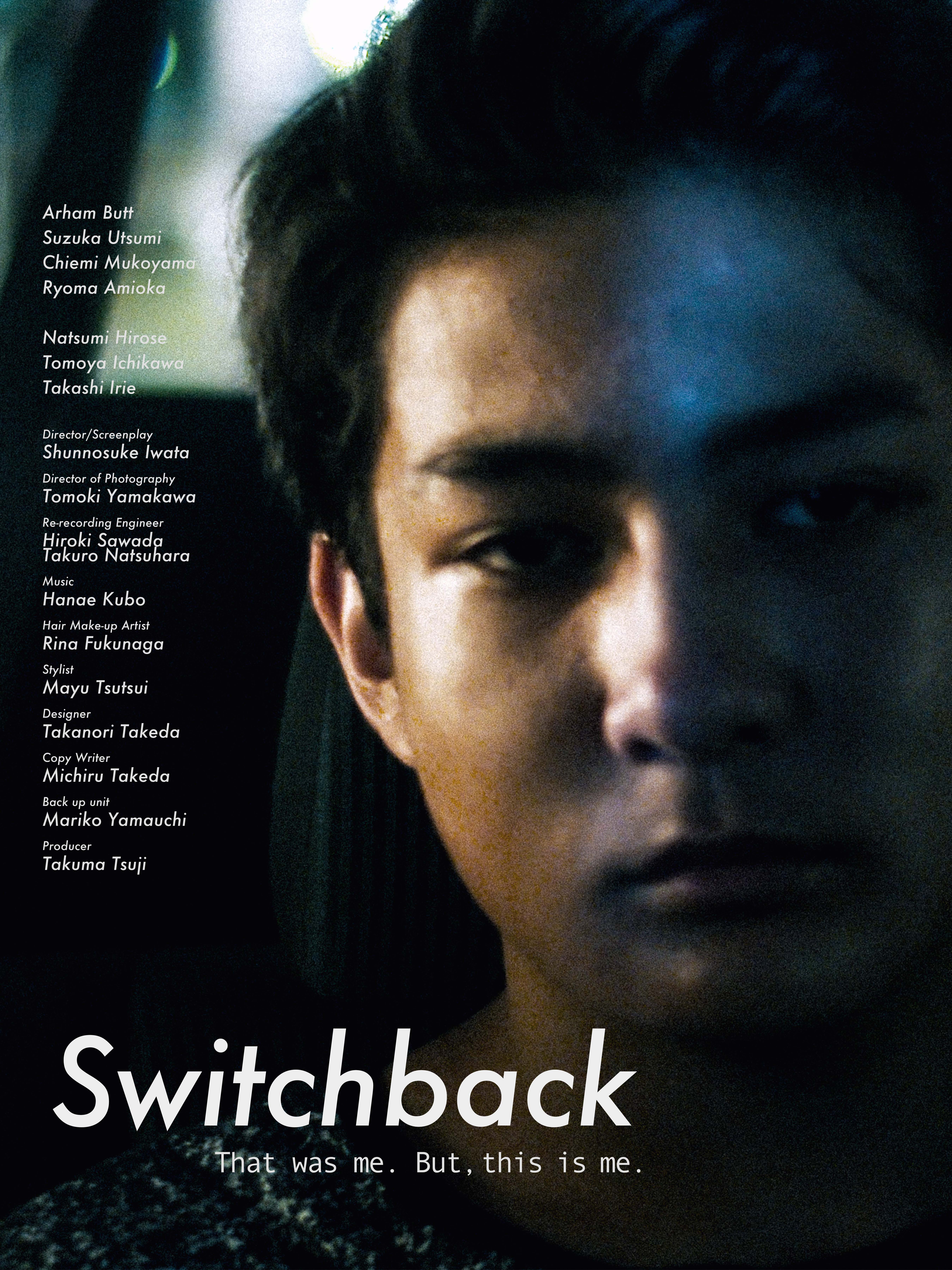

Really, everything in life is a learning experience but how should you feel if something that you thought was quite profound and serendipitous was actually engineered even if the way you reacted to it wasn’t? The young heroes of Shunnosuke Iwata’s Switchback (スイッチバック) find themselves caught in a moment of confusion uncertain how far they should trust the adult world while equally at odds with each other and trying to figure out what it is they may want out of life.

Brazilian-Japanese teenagers Arham and Chiemi are attending a summer workshop project along with basketball enthusiast Suzuka while her childhood friend Eiichiro never actually shows up. Led by Tokyo influencer Rei, the kids will be working together in order to produce a video of a ball bouncing through the countryside. By reversing the footage to make it seem as if the ball is on its own little adventure she hopes to create a sense of the uncanny and with it a new perspective. Arham doesn’t quite get the point of it, but participates anyway and ends up forming a special bond with an old man in a wheelchair they encounter who has a hobby of flying drones. Yet when he finally arrives, Eiichiro claims to have seen the old man walking around and accepting something from Rei assuming he must be some kind of stooge and the children’s adventure they’ve all been on since has been a setup.

Arham is very invested in the old man’s story and outright rejects Eiichiro’s suggestions that he isn’t “real”, carrying out an investigation into everything he told them about a former airfield that had been built in their town during the war and was later bought by a media company for recording aerial footage. What he discovers is that all of that seems to be true save for one crucial personal detail the old man had mentioned, leaving a grain of doubt in his mind while he continues to resent Eiichiro despite being unable to come up with a reason as to why he would lie. Eiichiro is in fact not quite telling the whole truth though he’s right about the old man, engaging in a kind of engineered adventure of his own but later offers the explanation that adults too are often frustrated and they may have tried to “destroy” Arham because they’re jealous of his cheerful and openhearted nature.

Even though he concedes that he still experienced what he experienced for himself after meeting the old man, developing an interest in drones and learning a lot of local and aviation history, Arham is uncertain how he should feel about being manipulated, disappointed on trying to confront Rei and hearing exactly the same speech as she’d used in her influencer videos explaining her approach to life and art aiming to give young people a head start in gaining new experiences without them realising that they’re being taught something even if she doesn’t otherwise attempt to push them in a particular direction simply provide the catalyst for growth. Chiemi experiences something similar when she’s offered the opportunity to become a model, a skeevy older man repeatedly telling her she is suited to the work and may have a promising future, adding that she has a quality of ferocity that “Japanese” kids don’t while she complains that she dislikes being told what does and doesn’t suit her preferring to do as she pleases whether other people think it suits her or not.

Suzuka meanwhile quietly struggles to fit in on her own having come to the town only eight years previously hinting that she and her family may have moved in the wake of the 2011 earthquake but stating only that she doesn’t like to talk of it either traumatised or fearing stigmatisation. Unity came first security second she claims of her basketball team reflecting on the positivity she experienced as they came together before a match in the face of their opponents. The kids perhaps do something similar as they each in their own way react to adult duplicity while deciding to take it in their stride embracing the experiences they’ve had as their own. Rei’s social experiment could easily have backfired leaving them cynical and indifferent, unwilling to believe in or pursue anything fearing that there is no objective truth only manipulation but in they end they run the other way, deciding to trust each other and themselves while creating new experiences of their own. Produced in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the town of Obu in rural Aichi Prefecture, Iwata captures the beauty of the local landscape along with the natural openness it engenders in allowing the children to become fully themselves as they ride their own individual switchbacks to adulthood.

Switchback screened as part of Osaka Asian Film Festival 2022

Original trailer (no subtitles)