Robots aren’t programmed to love autonomously according to Oliver (Shin Joo-hyup), a helperbot seemingly abandoned by his long lost owner, or as he terms it, friend, James in Lee Won-hoi’s quirky musical romance, My Favourite Love Story (어쩌면 해피엔딩, eojjeomyeon happy ending). It’s an odd thing to say in a way, what does it mean to love “autonomously”? Or perhaps he is simply alluding to the fact that there must obviously be some robots who are programmed for love even if “love” is as good a word as any to describe the way he’s bonded to James that causes him to wait by the window like a wife willing her husband back from the war.

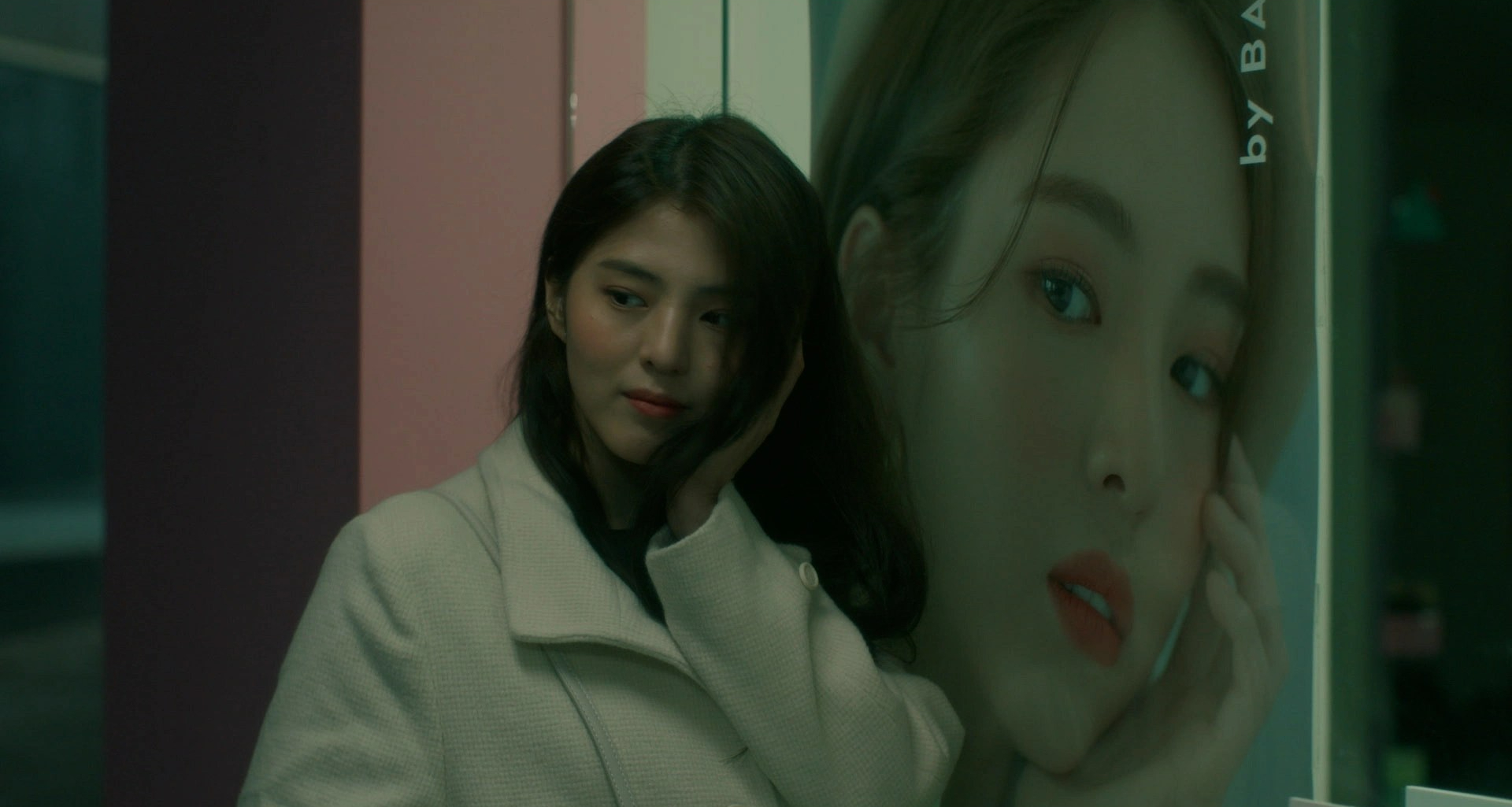

Oliver rarely leaves the apartment and enjoys conversation only with a handful of potted plants and the postman who delivers vintage copies of Life magazine, jazz records, and repair kits daily. We can see that Oliver’s word is small and frozen in time, though he looks out on a Seoul that seems to him a paradise while we’re told that it’s so polluted people have started evacuating to Jeju Island. It’s because of the pollution that production of helper robots has been stopped along with that of repair kids. There is something quite poignant about the forced ageing Oliver undergoes having been abandoned by a society that valued him only for his usefulness and now prevents him from being able to repair himself as if he were suddenly denied basic medical treatment and regarded always as a lesser being. On the road trip he eventually takes with the more cynical Claire (Kang Hye-in), he encounters signs that reads “no robots” while doing his best to act human despite his obvious awkwardness.

While Oliver is upbeat and content to wait for James certain that he’ll one day return, Claire is carrying heavier baggage stemming from her treatment by her former owners that convinces her humans are all bad and ready to discard them at any moment. Needing to borrow his charger, she bamboozles her way into Oliver’s life and convinces him to go on a trip to Jeju to look for James and unexpectedly finds herself falling in love along the way. But as Oliver says, love isn’t something that’s in their programming. After all, love causes lots of problems so why would we code it into machines we’ve built solely to serve us?

In any case, the discovery they make is that love is sad and also impossible in the knowledge that will someday inevitably end. Claire’s needs for repairs are more urgent than Oliver’s, while the world around them also seems to be crumbling and not least because of human negligence. They consider simply editing their memories to remove the new discoveries they’ve made about themselves and the world not to mention love in order to return to the state of inertia in which they existed before each just waiting for something while quietly falling apart.

Adapted from a one act fringe musical, the score has a contemporary Broadway feel which perhaps isn’t surprising given that it was written by an American musical theatre composer and sparked for the book writer by a chance encounter with the Damon Albarn song Everybody Robots in Brooklyn. Thematically, it asks whether it’s worth paying the price of love given that every romance has an expiry date even if theoretically a robot to could live forever were it not for humanity destroying the planet and then callously abandoning them. The original title translates as the more apt “maybe happy ending” hinting at the sense of inevitability in the pair’s constant reunions and desire for reconnection though they still seem reluctant to place their faith in love alone even as the world around them continues to improve and the skies above Seoul are clear once again. With its retro aesthetics and cineliteracy, the film ads a degree of timelessness to its quirky tale of robots finding love while attempting to deal with their abandonment issues in a world of human indifference and in fact settles for a different kind of inertia in the cycle of a tentative romance that might one day result in a happy ending.

My Favorite Love Story screened as part of the 18th Season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

International trailer (English subtitles)