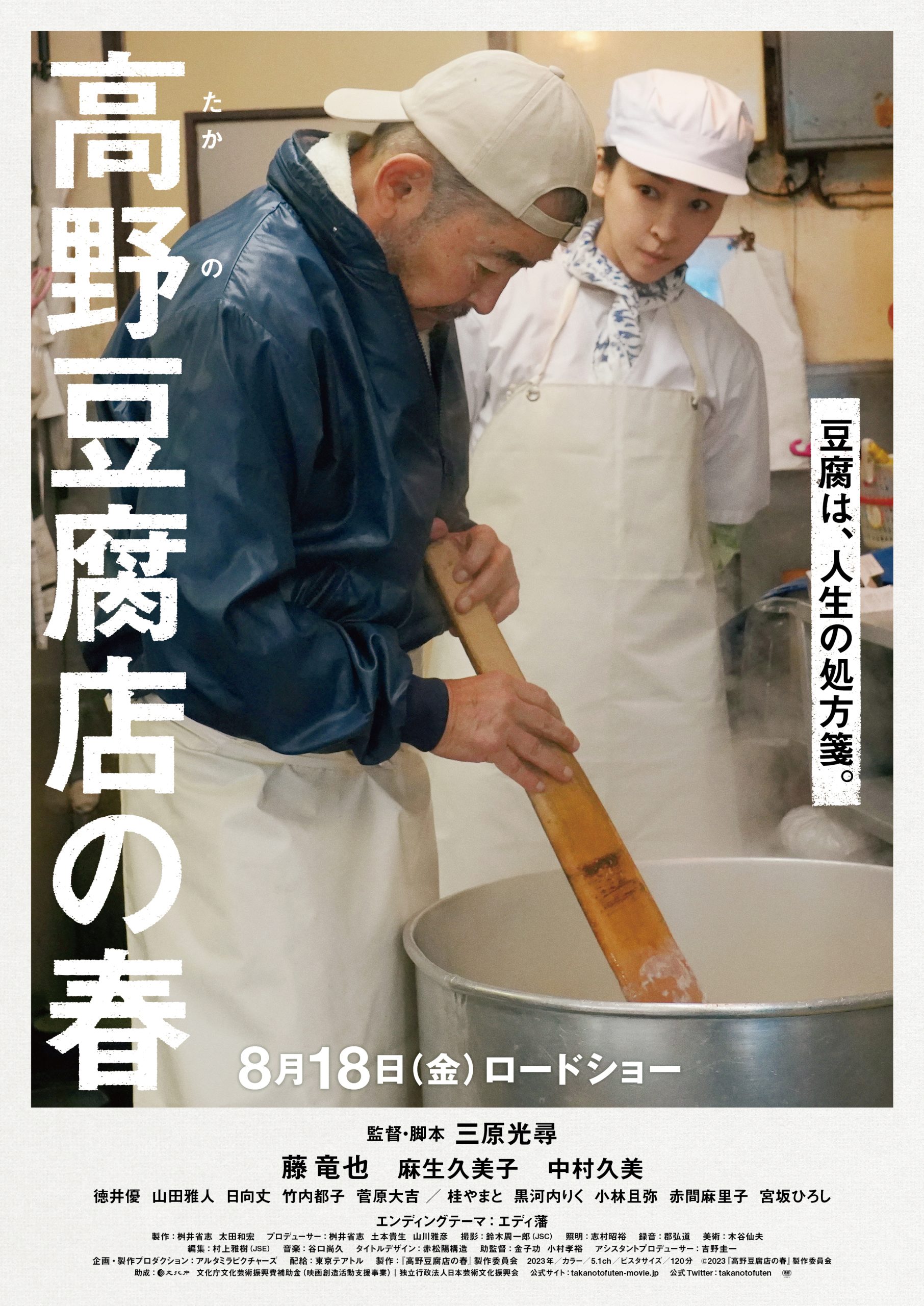

There’s an untranslated title card at the beginning of Mitushiro Mihara’s poignant dramedy Takano Tofu (高野豆腐店の春, Takano Tofu-ten no Haru) that describes the film as a story about the end of Heisei and it is in many ways about the end of an era, or perhaps of eras, but equally new beginnings and the eternal wellspring of life. With subtle hints of Ozu playing out as a kind of mashup of Late Autumn and Late Spring, it suggests that it’s never really too late to find happiness or to start something new even while preserving the best of the old.

Harbingers of change are, however, lingering on the horizon as a customer to Takano Tofu remarks agreeing with daughter Haru (Kumiko Aso) that they need to innovate to stay in the game when the big new supermarket opens a few streets away. But change is not something father Tatsuo (Tatsuya Fuji) is keen on and especially when it comes to his tofu which is why he’s cancelled Haru’s popular new product of fried tofu and cheese despite its popularity and is also dead against her idea of expanding their network to sell in Tokyo.

There is something inherently comforting about the peacefulness of this quiet corner of Onomichi as Mihara captures it even if it also seems like a place out of time more Showa even than Heisei with its family businesses and old-fashioned shopping arcade. But equally there’s an underlying loneliness and answered longing along with a sense of lives disrupted by historical circumstance. Ironically enough, Tatsuo receives news from the hospital that one of the arteries to his heart is blocked requiring an operation to get everything working again and then immediately bumps into an old woman about his own age with whom he eventually bonds over the shared traumas of living in post-war Japan along with the lingering social stigma towards those affected by the dropping of the atomic bomb. We later learn that the failure of Haru’s marriage was in part caused by her father-in-law’s prejudice fearing her irradiated genes would contaminate his bloodline.

Then again, perhaps the pity expressed towards Fumie (Kumi Nakamura) as a woman who never married plays into outdated and sexist social attitudes that also lead Tatsuo and his friends to decide to find a mate for Haru given his sudden mortality crisis and fear that like Fumie she will be left alone when he eventually passes away. Of course, what it amounts to is a bunch of old men trying to decide who a middle-aged woman should marry while deliberately avoiding asking her if that’s even something she’s interested in. Having experienced marriage already perhaps she’s no desire to do so again and is perfectly happy the way things are. In any case she’s infinitely capable of finding a husband for herself if she wanted one. The prospective match they come up with for her is perfect on paper, youngish, handsome, wealthy and cultured, yet as it turns out what Haru might prefer is someone more ordinary, down to earth, and straightforward ironically enough just like tofu.

As she later says, Tatsuo’s tofu has the flavour he gives it. Nicely textured, surprisingly soft on the inside, with a slight hint of astringency. There may be a minor pun involved in the Japanese title in that it can be read either as “Haru of Takano Tofu”, or as the meaning of her name implies “Spring at Takano Tofu” hinting both at a sense of transience and resurgence as Tatsuo takes in the cherry blossoms with Fumie and reflects on all they’ve experienced throughout the long years, the hardship and heartbreak of the post-war era. Yet as he says life is for living and it’s as much as you can hope for to look back and laugh at a life well lived. Maybe some things don’t need to change all that much, like carefully produced artisanal tofu as rich in soul as those who make it, but there’s always room for a little innovation and tiny chances for new happiness that could easily pass you by if you aren’t willing to take a risk or two and place a bet on change.

Takano Tofu screened as part of the 18th Season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II.

A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II.