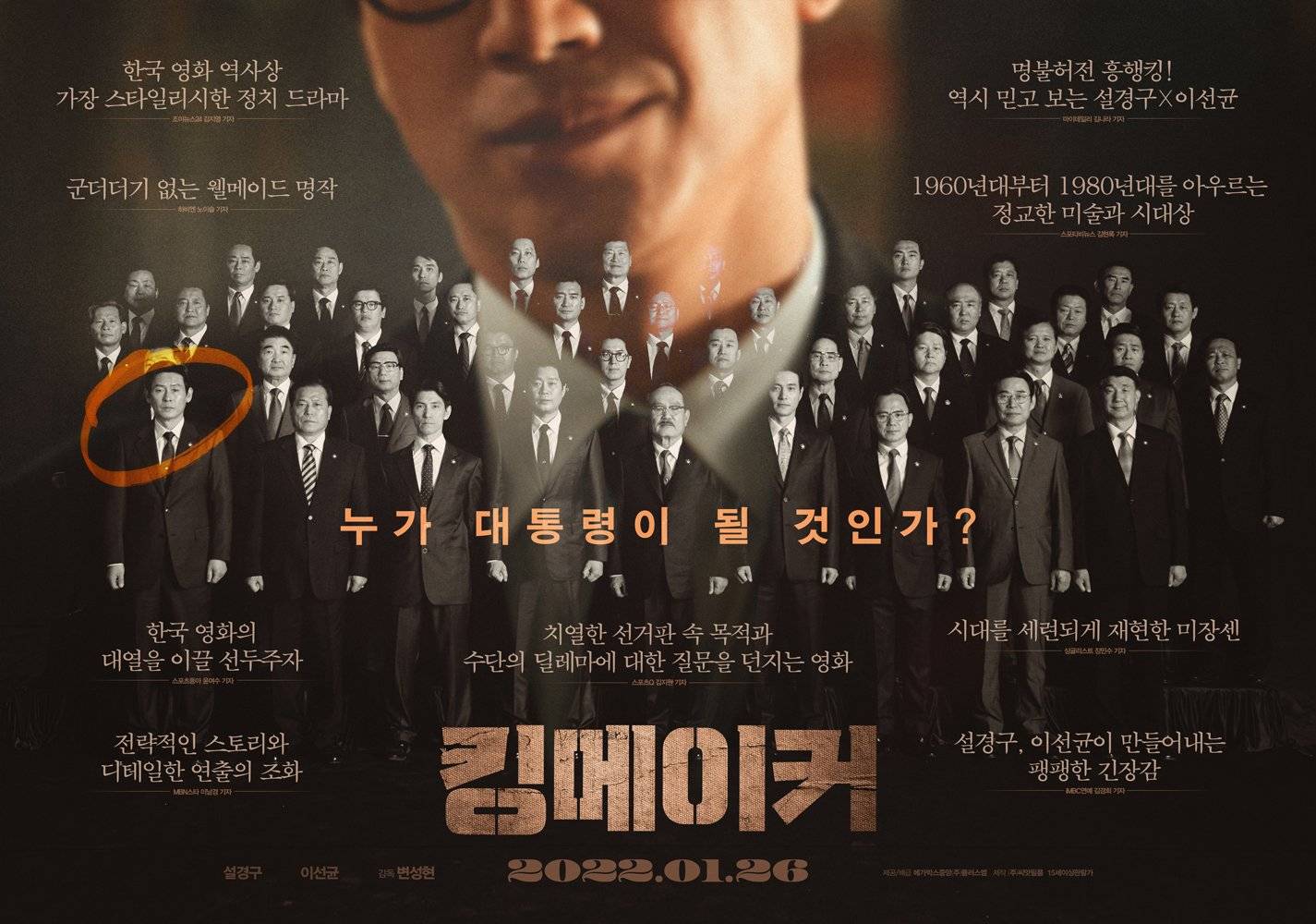

It’s the political paradox. You can’t do anything without getting elected but to get elected you might have to abandon whatever it was you wanted to do in the first place. Loosely based on the real life figures of Kim Dae-jung and his political strategist Eom Chang-rok, the heroes of Byun Sung-hyun’s Kingmaker (킹메이커) are obsessed with the question of whether the ends justify the means and if it’s possible to maintain integrity in politics when the game itself is crooked while the film suggests that in the end you will have to live with your choices and your compromises either way and if it’s a better world you want to build perhaps you can’t get there by cheating your way to paradise.

The son of a North Korean migrant, Seo Chang-dae (Lee Sun-kyun) is an embittered and frustrated pharmacist with a talent for spin. When his friend complains about a neighbour stealing his eggs from his chicken coop and denying all knowledge because he’s well connected and knows he can get away with it, Chang-dae’s advice is to plant one of his own chickens in the other guy’s coop and catch him red handed. Impressed by the impassioned political speechmaking of labour activist Kim Woon-bum (Sol Kyung-gu), he writes him a letter offering his services and then marches down to his office to convince him that he is the guy to break his losing streak and finally get him elected so they can “change the damned world”.

The problem is that all of Chang-dae’s ideas are like the chicken scam, built on the manipulation of the truth, but you can’t deny that they work. He plays the other side, the increasingly authoritarian regime of Park Chung-hee, at their own game, getting some of their guys to dress up as the opposing party and then set about offending a bunch of farmers by being generally condescending and entitled. They stage fights and perform thuggish violence to leave the impression that Park’s guys are oppressive fascists while asking for the “gifts” the Park regime had given out to curry favour back to further infuriate potential voters. Later some of their own guys turn up with the same gifts to send the message that they’re making up for all Park’s mistakes. At one point, Chang-dae even suggests staging an attack on Woon-bum’s person to gain voter sympathy, an idea which is met with total disdain by Woon-bum and his team many of whom are at least conflicted with Chang-dae’s underhanded tactics.

But then as he points out, if they want to create a better, freer Korea in which people can speak their minds without fear then they have to get elected first. It may be naive to assume that you can behave like this and then give it all up when finally in office, but Chang-dae at least is committed to the idea that the ends justify the means. Woon-bum meanwhile is worried that Chang-dae has lost sight of what the ends are and is solely focussed on winning at any cost. He has an opposing number in slimy intelligence agent Lee (Jo Woo-Jin) who serves Park in much the same way Chang-dae serves Woon-bum, but Chang-dae fatally misunderstands him, failing to appreciate that for Lee Park’s “revolution” is also a just cause for which he is fighting just as Chang-dae is fighting for freedom and democracy. In an uncomfortable touch, Lee seems to be coded as gay with his slightly effeminate manner and tendency towards intimate physical contact adding an additional layer to his gradual seduction of Chang-dae whose friendship with Woon-bum also has its homoerotoic qualities in its quiet intensity.

The final dilemma lies in asking whether or not Woon-bum could have won the pivotal election of 1971, preventing Park from further altering the constitution to cement his dictatorship and eventually declaring himself president for life, if he had not parted ways with Chang-dae and tried to win more “honestly”. If so, would they have set Korea on a path towards the better world they envisaged or would they have proved little different, their integrity already compromised by everything they did to get there poisoning their vision for the future? The fact that history repeats itself, Woon-bum and his former rival Young-ho (Yoo Jae-myung) splitting the vote during the first “democratic” presidential election and allowing Chun Doo-hwan’s chosen successor to win, perhaps suggests the latter. In any case, it’s Chang-dae who has to live with his choices in having betrayed himself, as Woon-bum had feared too obsessed with winning to remember why he was playing in the first place. “All my ideas about justice were brought down by my own hand” he’s forced to admit, left only with self-loathing defeat in his supposed victory. Some things don’t change, there is intrigue in the court, but “putting ambition before integrity will get you nowhere” as Chang-dae learns to his cost.

Kingmaker screened as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)