Conventional wisdom states it’s better not to get involved with the yakuza. According to Hamon: Yakuza Boogie (破門 ふたりのヤクビョーガミ Hamon: Futari no Yakubyogami), the same goes for sleazy film execs who can prove surprisingly slippery when the occasion calls. Based on Hiroyuki Kurokawa’s Naoki Prize winning novel and directed by Shotaro Kobayashi who also adapted the same author’s Gold Rush into a successful WOWWOW TV Series, Hamon: Yakuza Boogie is a classic buddy movie in which a down at heels slacker forms an unlikely, grudging yet mutually dependent relationship with a low-level gangster.

Conventional wisdom states it’s better not to get involved with the yakuza. According to Hamon: Yakuza Boogie (破門 ふたりのヤクビョーガミ Hamon: Futari no Yakubyogami), the same goes for sleazy film execs who can prove surprisingly slippery when the occasion calls. Based on Hiroyuki Kurokawa’s Naoki Prize winning novel and directed by Shotaro Kobayashi who also adapted the same author’s Gold Rush into a successful WOWWOW TV Series, Hamon: Yakuza Boogie is a classic buddy movie in which a down at heels slacker forms an unlikely, grudging yet mutually dependent relationship with a low-level gangster.

Ninomiya (Yu Yokoyama), a classic slacker, makes ends meet by acting as a kind of liaison officer between the normal world and the yakuza one. His contact, Kuwahara (Kuranosuke Sasaki), is a scary looking guy but as yakuza go not so bad to work with. Following the government’s organised crime crackdown, Ninomiya finds himself at more of a loose end and so when an elderly film director, Koshimizu (Isao Hashizume), comes to him and asks to meet a yakuza first hand, Ninomiya sets up a meeting. Yakuza and movies can be a dangerous mix but somehow or other Koshimizu manages to charm the pair and even gets Kuwahara’s boss, Shimada (Jun Kunimura), to invest some of his own money.

Unfortunately, this is when things start to go wrong. Koshimizu’s pretty “daughter” is really his mistress (as Kuwahara suspected) and the wily old bugger has taken off for the casino paradise of Macao with both the beautiful woman and suitcase full of yakuza dough. Kuwahara is now in a lot of trouble and ropes in Ninomiya to help him sort it out but in their pursuit of Koshimizu they eventually find themselves caught up in a series of turf wars.

Yakuza comedies have a tendency towards unexpected darkness but Hamon’s key feature is its almost childish innocence as Ninomiya and Kuwahara go about their business with relatively few genuinely life threatening incidents. Though the pair bicker and argue with Ninomiya always secretly afraid of his big gangster buddy and Kuwahara fed up with his nerdy friend’s lack of know how, the relationship they’ve developed is an intensely co-dependent one which fully supports the slightly ironic “no me without you” message. Eventually growing into each other, Ninomiya and Kuwahara move increasingly into the other’s territory before finally re-encountering each other on more equal footing.

These are less rabid killers than a bunch of guys caught up in a silly game. Shady film director Koshimizu turns out to be some sort of cartoon hero, perpetually making a sprightly and unexpected escape despite his advanced age while the toughened gangsters hired to keep him locked up find themselves one hostage short time after time. Ninomiya’s worried cousin Yuki (Keiko Kitagawa) keeps trying to talk him into a more ordered way of life which doesn’t involve so much hanging round with scary looking guys in suits, but Ninomiya is reluctant to leave the fringes of the underworld even if he seems afraid for much of the time. Kuwahara is a yakuza through and through, or so he thinks. This latest saga has left him in an embarrassing position with his bosses, not to mention the diplomatic incident with a rival gang, all of which threatens his underworld status and thereby essential identity.

Still, all we’re talking about here is having a little more time for solo karaoke, not being bundled into the boot of a car and driven to a remote location. Filled with movie references and slapstick humour this is a yakuza tale inspired by classic cinematic gangsters rather than their real world counterparts but it still has a few things to say about human nature in general outside of the fictional. An odd couple, Ninomiya and Kuwahara couldn’t be more different but besides the fact they don’t quite get along, they make a good team. No me without you indeed, solo stakeouts are boring, even if you do bicker and fuss the whole time it’s good to know there’s someone who’ll always come back for you (especially if you tell them not to) ready to take the wheel.

Hamon: Yakuza Boogie was screened at the 19th Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Corruption has become a major theme in Korean cinema. Perhaps understandably given current events, but you’ll have to look hard to find anyone occupying a high level corporate, political, or judicial position who can be counted worthy of public trust in any Korean film from the democratic era. Cho Ui-seok’s Master (마스터) goes further than most in building its case higher and harder as its sleazy, heartless, conman of an antagonist casts himself onto the world stage as some kind of international megastar promising riches to the poor all the while planning to deprive them of what little they have. The forces which oppose him, cerebral cops from the financial fraud devision, may be committed to exposing his criminality but they aren’t above playing his game to do it.

Corruption has become a major theme in Korean cinema. Perhaps understandably given current events, but you’ll have to look hard to find anyone occupying a high level corporate, political, or judicial position who can be counted worthy of public trust in any Korean film from the democratic era. Cho Ui-seok’s Master (마스터) goes further than most in building its case higher and harder as its sleazy, heartless, conman of an antagonist casts himself onto the world stage as some kind of international megastar promising riches to the poor all the while planning to deprive them of what little they have. The forces which oppose him, cerebral cops from the financial fraud devision, may be committed to exposing his criminality but they aren’t above playing his game to do it.

Back in the real world, politics has never felt so unfunny. This latest slice of unlikely political satire from Japan may feel a little close to home, at least to those of us who hail from nations where it seems perfectly normal that the older men who make up the political elite all attended the same school and fully expected to grow up and walk directly into high office, never needing to worry about anything so ordinary as a career. Taking this idea to its extreme, elite teenager Teiichi is not only determined to take over Japan by becoming its Prime Minister, but to start his very own nation. In Teiichi: Battle of Supreme High (帝一の國, Teiichi no Kuni) teenage flirtations with fascism, homoeroticism, factionalism, extremism – in fact just about every “ism” you can think of (aside from altruism) vie for the top spot among the boys at Supreme High but who, or what, will finally win out in Teiichi’s fledging, mental little nation?

Back in the real world, politics has never felt so unfunny. This latest slice of unlikely political satire from Japan may feel a little close to home, at least to those of us who hail from nations where it seems perfectly normal that the older men who make up the political elite all attended the same school and fully expected to grow up and walk directly into high office, never needing to worry about anything so ordinary as a career. Taking this idea to its extreme, elite teenager Teiichi is not only determined to take over Japan by becoming its Prime Minister, but to start his very own nation. In Teiichi: Battle of Supreme High (帝一の國, Teiichi no Kuni) teenage flirtations with fascism, homoeroticism, factionalism, extremism – in fact just about every “ism” you can think of (aside from altruism) vie for the top spot among the boys at Supreme High but who, or what, will finally win out in Teiichi’s fledging, mental little nation? South Korean cinema has a fairly ambivalent attitude to its policemen. Most often, detectives are a bumbling bunch who couldn’t find the killer even if he danced around in front of them shouting “it was me!” whereas street cops are incompetent, lazy, and cowardly. That’s aside from their tendency towards violence and corruption but rarely has there been a policeman who gets himself into trouble solely for being too nice and too focussed on his family. Confidential Assignment (공조, Gongjo), though very much a mainstream action/buddy cop movie, is somewhat unusual in this respect as it pairs a goofy if skilled and well-meaning South Korean police officer, with an outwardly impassive yet inwardly raging North Korean special forces operative.

South Korean cinema has a fairly ambivalent attitude to its policemen. Most often, detectives are a bumbling bunch who couldn’t find the killer even if he danced around in front of them shouting “it was me!” whereas street cops are incompetent, lazy, and cowardly. That’s aside from their tendency towards violence and corruption but rarely has there been a policeman who gets himself into trouble solely for being too nice and too focussed on his family. Confidential Assignment (공조, Gongjo), though very much a mainstream action/buddy cop movie, is somewhat unusual in this respect as it pairs a goofy if skilled and well-meaning South Korean police officer, with an outwardly impassive yet inwardly raging North Korean special forces operative.

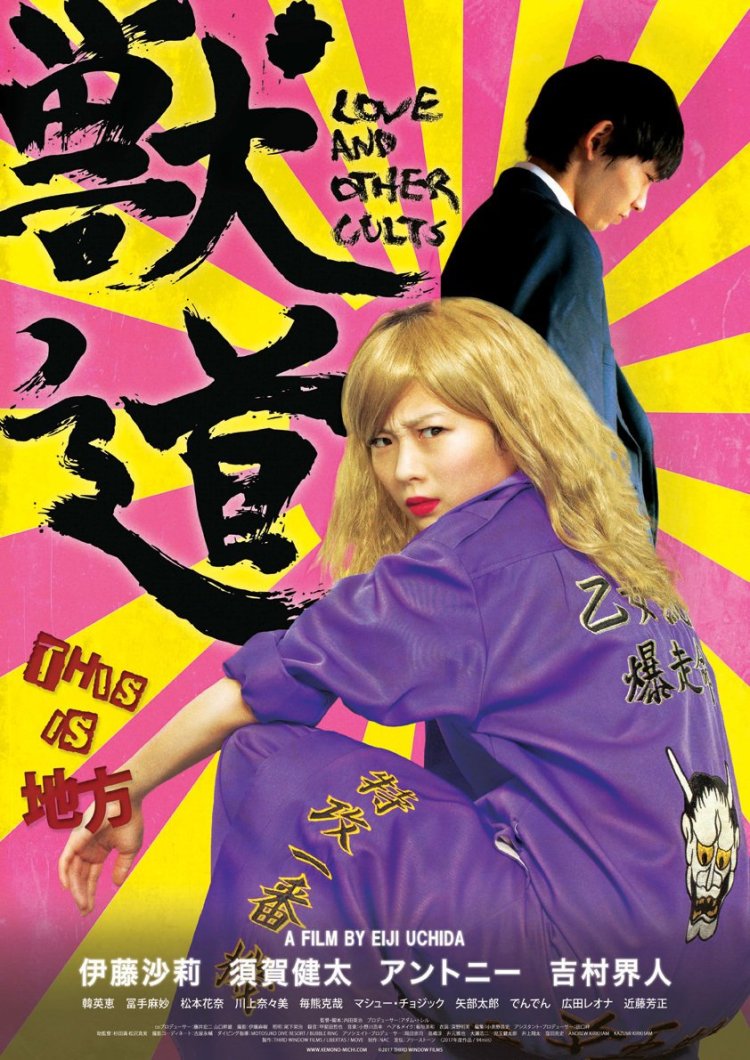

Eiji Uchida’s career has been marked by the stories of self defined outsiders trying to decide if they want to move towards or further away from the centre, but in his latest film Love and Other Cults ( 獣道, Kemonomichi), he seems content to let them linger on the margins. The title, neatly suggesting that perhaps love itself is little more than a ritualised set of devotional acts, sets us up for a strange odyssey through teenage identity shifting but where it sends us is a little more obscure as a still young man revisits his youthful romance only to find it as wandering and ill-defined as many a first love story and like many such tales, one ultimately belonging to someone else.

Eiji Uchida’s career has been marked by the stories of self defined outsiders trying to decide if they want to move towards or further away from the centre, but in his latest film Love and Other Cults ( 獣道, Kemonomichi), he seems content to let them linger on the margins. The title, neatly suggesting that perhaps love itself is little more than a ritualised set of devotional acts, sets us up for a strange odyssey through teenage identity shifting but where it sends us is a little more obscure as a still young man revisits his youthful romance only to find it as wandering and ill-defined as many a first love story and like many such tales, one ultimately belonging to someone else. The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry, as the old saying goes, but for four down at heels street kids even their meagre attempts to evade a desperate situation land them in even more trouble than they’ve ever been in before. The debut feature from director Lee Sung-tae, Derailed (두 남자, Doo Namja) is bleak and gritty though underpinned by an ironic sense of love and connection which is itself often “derailed” or subverted as genuine feeling becomes a tool to be exploited in the ongoing war between those fighting amongst themselves to get a hand on the bottom rung of the ladder.

The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry, as the old saying goes, but for four down at heels street kids even their meagre attempts to evade a desperate situation land them in even more trouble than they’ve ever been in before. The debut feature from director Lee Sung-tae, Derailed (두 남자, Doo Namja) is bleak and gritty though underpinned by an ironic sense of love and connection which is itself often “derailed” or subverted as genuine feeling becomes a tool to be exploited in the ongoing war between those fighting amongst themselves to get a hand on the bottom rung of the ladder. Hiroshi Nishitani has spent the bulk of his career working in television. Best known for the phenomenally popular Galileo starring Masaharu Fukuyama which spawned a number of big screen spin-offs including an adaptation of the series’ inspiration The Devotion of Suspect X and

Hiroshi Nishitani has spent the bulk of his career working in television. Best known for the phenomenally popular Galileo starring Masaharu Fukuyama which spawned a number of big screen spin-offs including an adaptation of the series’ inspiration The Devotion of Suspect X and

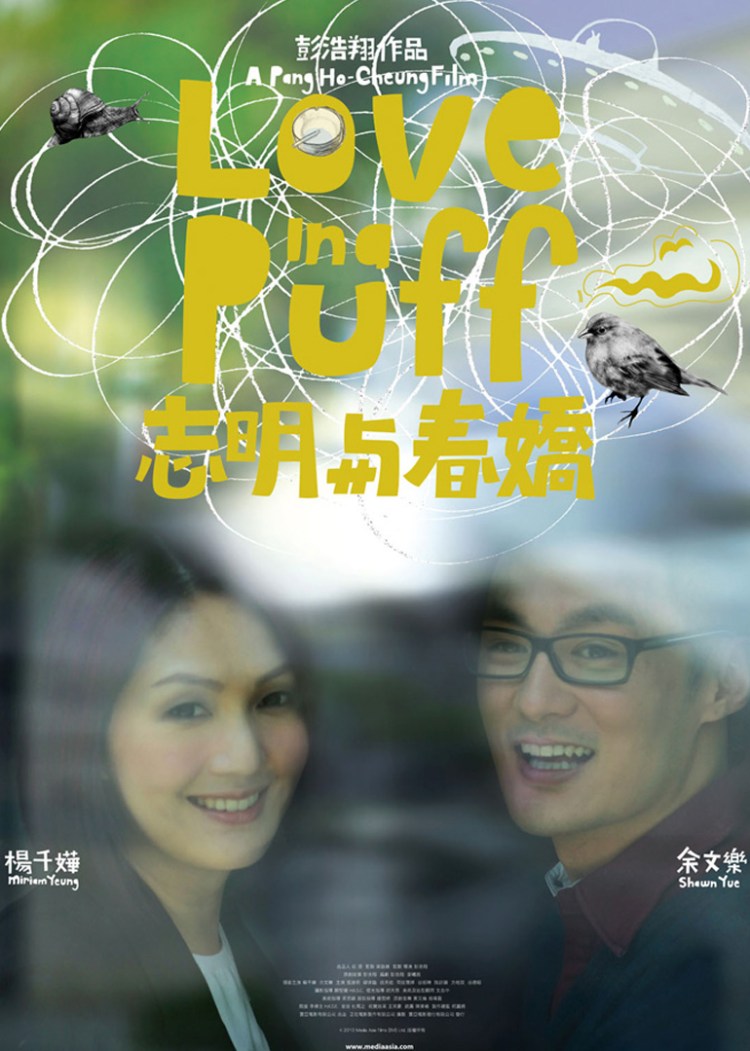

Jimmy and Cherie, against all the odds, are still together and in a happy longterm relationship in the third addition to Pang Ho-cheung’s series of charming romantic comedies, Love off the Cuff (春嬌救志明). Following the dramatic declaration at the end of

Jimmy and Cherie, against all the odds, are still together and in a happy longterm relationship in the third addition to Pang Ho-cheung’s series of charming romantic comedies, Love off the Cuff (春嬌救志明). Following the dramatic declaration at the end of  Smokers. Is there a more maligned, ostracised group in the modern world? Considering the rapid pace at which their “harmless” pastime has become unacceptable, you can understand why they might feel particularly put out – literally, as they find themselves taking refuge in designated smoking areas or perhaps back allies where it seems no one’s looking. For all the nostalgia about how easy it was to strike up a friendship with a stranger just by asking for a light, it is also important to remember that smoking is not so “harmless” after all and there are reasons why smokers are asked to keep their activities amongst those who’ve also decided to ignore the warnings. The Smoking Ordinance, oddly enough, may have accidentally boosted the social potential of a smoke as those eager for a puff are given additional reasons to spend time together in an enclosed space, building a sense of community through nicotine addiction.

Smokers. Is there a more maligned, ostracised group in the modern world? Considering the rapid pace at which their “harmless” pastime has become unacceptable, you can understand why they might feel particularly put out – literally, as they find themselves taking refuge in designated smoking areas or perhaps back allies where it seems no one’s looking. For all the nostalgia about how easy it was to strike up a friendship with a stranger just by asking for a light, it is also important to remember that smoking is not so “harmless” after all and there are reasons why smokers are asked to keep their activities amongst those who’ve also decided to ignore the warnings. The Smoking Ordinance, oddly enough, may have accidentally boosted the social potential of a smoke as those eager for a puff are given additional reasons to spend time together in an enclosed space, building a sense of community through nicotine addiction. The world of shojo manga is a particular one. Aimed squarely at younger teenage girls, the genre focuses heavily on idealised, aspirational romance as the usually female protagonist finds innocent love with a charming if sometimes shy or diffident suitor. Then again, sometimes that all feels a little dull meaning there is always space to send the drama into strange or uncomfortable areas. Policeman and Me (PとJK, P to JK), adapted from the shojo manga by Maki Miyoshi is just one of these slightly problematic romances in which a high school girl ends up married to a 26 year old policeman who somehow thinks having an official certificate will make all of this seem less ill-advised than it perhaps is.

The world of shojo manga is a particular one. Aimed squarely at younger teenage girls, the genre focuses heavily on idealised, aspirational romance as the usually female protagonist finds innocent love with a charming if sometimes shy or diffident suitor. Then again, sometimes that all feels a little dull meaning there is always space to send the drama into strange or uncomfortable areas. Policeman and Me (PとJK, P to JK), adapted from the shojo manga by Maki Miyoshi is just one of these slightly problematic romances in which a high school girl ends up married to a 26 year old policeman who somehow thinks having an official certificate will make all of this seem less ill-advised than it perhaps is.